The Rosenau Experiment: The 1918 Influenza Pandemic & The Failed Quest to Prove How It Spread

📌 Discover the groundbreaking but baffling 1918-1919 Rosenau Experiment, where scientists failed to transmit the deadly influenza virus under controlled conditions. Learn how this experiment challenged medical assumptions, influenced pandemic research, and reshaped our understanding of viral transmission. A must-read for historians, educators, and public health researchers.

Dr. Milton Rosenau, nd, circa 1910. GGA Image ID # 17263a0377

📜 The Rosenau Experiment & The Mystery of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

🔍 A Scientific Puzzle in the Midst of a Global Crisis

The Rosenau Experiment (1918-1919) is one of the most fascinating and perplexing scientific investigations conducted during the Influenza Pandemic of 1918, a deadly outbreak that killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide. Led by Dr. Milton Joseph Rosenau and conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service and the U.S. Navy, this experiment aimed to determine how influenza spread and whether it could be intentionally transmitted under controlled conditions.

Surprisingly, despite direct exposure to infected patients, nasal and throat inoculations, and even injections of infected blood, not a single volunteer developed the flu. This shocking result challenged prevailing assumptions about how the virus was transmitted and left scientists baffled.

This page provides an invaluable resource for historians, educators, genealogists, and researchers seeking to understand:

✔ The scientific and medical challenges of studying a fast-moving pandemic

✔ How early epidemiologists attempted to isolate the influenza virus

✔ The broader implications of failed transmission experiments in understanding viral infections

Study of Influenza at Harvard University. —It has been announced that exhaustive research into the causes, effects, and complications of influenza, together with their prevention and cure, will be carried on by the laboratories of Harvard University.

This work has been made possible by a gift of $50,000 by a corporation that suffered losses during the epidemic last year. The greater part of this sum will be used by Dr. Milton Joseph Rosenau, Professor of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene of the Harvard Medical School, and a corps of assistants.

The research will be carried on in connection with Dr. Rosenau's teaching in the medical school, and the students will benefit from his discoveries. - Boston Medial and Surgical Journal, 9 October 1919: 470.

Summary of the Experiment in Public Health Report

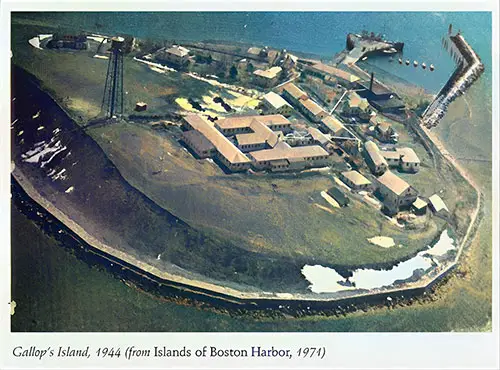

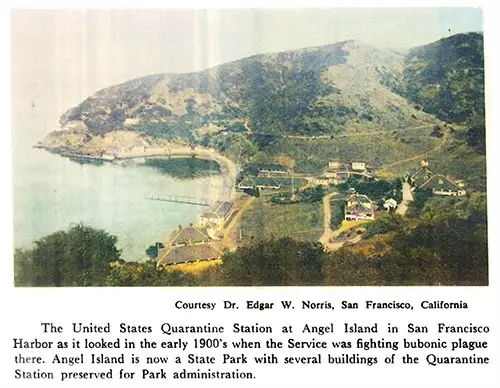

Perhaps the most interesting epidemiological studies conducted during the 1918-1919 pandemic were the human experiments conducted by the Public Health Service and the U.S. Navy under the supervision of Milton Rosenau on Gallops Island, the quarantine station in Boston Harbor, and on Angel Island, its counterpart in San Francisco.

The experiment began with 100 volunteers from the Navy who had no history of influenza. Rosenau was the first to report on the experiments conducted at Gallops Island in November and December 1918.

His first volunteers received first one strain and then several strains of Pfeiffer bacillus by spray and swab into their noses and throats and then into their eyes.

When that procedure failed to produce disease, others were inoculated with mixtures of other organisms isolated from the throats and noses of influenza patients. Next, some volunteers received injections of blood from influenza patients.

Finally, 13 of the volunteers were taken into an influenza ward and exposed to 10 influenza patients each. Each volunteer was to shake hands with each patient, to talk with him at close range, and to permit him to cough directly into his face.

None of the volunteers in these experiments developed influenza. Rosenau was clearly puzzled, and he cautioned against drawing conclusions from negative results.

He ended his article in JAMA with a telling acknowledgement: “We entered the outbreak with a notion that we knew the cause of the disease, and were quite sure we knew how it was transmitted from person to person. Perhaps, if we have learned anything, it is that we are not quite sure what we know about the disease.

The research conducted at Angel Island and that continued in early 1919 in Boston broadened this research by inoculating with the Mathers streptococcus and by including a search for filter-passing agents, but it produced similar negative results. It seemed that what was acknowledged to be one of the most contagious of communicable diseases could not be transferred under experimental conditions.

Dr. Milton Joseph Rosenau, Who Was Appointed by Surgeon General Whyman to Succeed Dr. Kinyoun as Director of the Hygienic Labatory. Photo Courtesy of the Nataional Library of Medicine, PHS. GGA Image ID # 22220d5643

Some Interesting Though Unsuccessful Attempts To Transmit Influenza Experimentally.

How great are the difficulties surrounding the study of the nature of the virus of influenza is indicated by the following summary of two series of experiments recently carried out, one at Boston and one at San Francisco.

BOSTON EXPERIMENTS

Gallop's Island, 1944 (From Islands of Boston Harbor, 1971). GGA Image ID # 2221a96fc9

These experiments were carried on jointly by Lieut. Commander M. J. Rosenau, Medical Corps, U. S. N. R. F., and Lieut. W. J. Keegan, Medical Corps, U. S. N. R. F. and by Surg. Joseph Goldberger and Asst. Surg. G. C. Lake, United States Public Health Service, at the United States Quarantine Station, Gallop’s Island, Boston, Mass.

The subjects of experiment were 68 volunteers from the United States Naval Detention Training Camp, Door Island, Boston. These volunteers had been exposed in some degree to an epidemic of influenza at the training camp or at some station prior to coming to Door Island; 47 of the men wore without history of an attack of influenza during the recent epidemic and 39 of those were without history of an attack of such illness at any time during their lives.

The experiments consisted of inoculations with pure cultures of Pfeiffer’s bacidus, with secretions from the upper respiratory passagos, and with blood from typical cases of influenza.

The study was begun on November 13 with an experiment in which a suspension of a freshly isolated culture of Pfeiffer’s bacillus was instilled into the nose of each of 3 nonimmunes and into 3 controls who had a history of an attack in the present epidemic.

None of these volunteers showed any reaction following this inoculation. Another experiment was made at a later date with a suspension of a number of different pure cultures of Pfeiffer’s bacillus, of which 4 were recently isolated. Ten presumably nonimmune volunteers wore inoculated, with the same negative results.

Three sets of experiments were made with secretions, both unfiltered and filtered, from the upper respiratory tract of typical cases of influenza in the active stage of the disease. In these experiments a total of 30 men were subjected to inoculation by means of spray, swab, or both, of the nose and throat.

The interval elapsing between securing secretions from the donors and inoculation of the volunteers was progressively reduced in these experiments so that in the third of the series the interval at most was 30 seconds. In no instance was an attack of influenza produced in any one of the subjects.

An experiment was made in which the members of one of the groups of volunteers which had been subjected to inoculation with secretions were exposed to a group of cases of influenza in the active stage of the disease in a manner intended to simulate conditions which in nature are supposed to favor the transmission of the disease.

Each of this group of 10 volunteers came into close association for a few minutes with each of 10 selected cases of influenza in the wards of the Chelsea Naval Hospital.

At the time the volunteers were exposed to this infection the cases were from 10 to 84 hours from the onset of their illness and 4 of them were not over 24 hours after the onset.

Each volunteer conversed a few minutes with each of the selected patients, who were requested to, and coughed into the face of each volunteer in turn, so that each volunteer was exposed in this manner to all 10 cases.

The total exposure amounted to about three-quarters of an hour for each volunteer. None of those volunteers developed any symptoms of influenza following this experiment.

Advantage was taken of the opportunity for making this study to attempt to confirm the reported positive results of transmission of influenza by Nicolle. Secretions from 5 typical cases of influenza were secured, filtered, and some of the filtrate was inoculated subcutaneously into each of the group of 10 volunteers.

At the same time blood was drawn from the same cases and pooled, and some of the mixed blood injected subcutaneously into each of another group of 10 volunteers.

The time lost between drawing the blood and inoculating it in no case exceeded three-quarters of an hour. None of the men subjected to these inoculations developed any evidences of illness.

In the foregoing experiments the patients serving as donors belonged to groups from epidemic foci either on shipboard or at institutions. The great majority indeed belonged in a group from an epidemic on board the U. S. S. Yacona. Of the personnel of this vessel, 95 in number, 80, or 84 percent, were stricken with the disease in an epidemic between November 17 and 29.

SAN FRANCISCO EXPERIMENTS.

Angel Island Quarantine Station in San Francisco Harbor circa Early 1900s. Photo by Dr. Edgar W. Norris, San Francisco. GGA Image ID # 22223e888e

The national quarantine station is located on Angel Island. Vessels are boarded by quarantine officers near Alcatraz Island and, if subject to inspection, must not pass beyond the line drawn from Point Stuart on Angel Island to the stack at the municipal pumping station at Black Point, San Francisco, until they have been granted pratique.

The quarantine anchorage is situated in the channel leading to San Pablo Bay midway between Bluff and San Quentin Points and 3 miles north-northwest of Angel Island, being marked by yellow buoys. Fumigation is conducted, as occasions require, either at the Angel Island Station or on the San Francisco side.

The following observations were carried out practically simultaneously with those described above. The work was done at the Angel Island Quarantine Station, San Francisco, Cal., utilizing volunteers from the Yerba Buena Naval Training Station, San Francisco.

The experiments were carried on jointly by Surg. G. W. McCoy, of the United States Public Health Service, and Lieut. De Wayne Richey, United States Navy.

The volunteers who were used in these experiments differed from those used at Boston in two respects—first, the personnel of the Yerba Buena Station had not been exposed to influenza in the present epidemic and were therefore presumed not to possess any special natural immunity; second, all of the men had been vaccinated with large doses of a bacterial vaccine containing Pfeiffer’s bacilli, the three fixed types of pneumococci and hæmolytic streptococci.

We are not prepared at present to state what influence this vaccination may have had in promoting resistance to influenza infection, but if we may judge by the results of controlled experiments elsewhere such vaccination may for the present purpose be ignored.

Editorial Note

The foregoing experiments, though extremely interesting, do not, of course, warrant final conclusions. It is hoped that it may be possible to carry the studies further and that results may be obtained that will definitely settle the nature and the modo of spread of the virus of epidemic influenza.

For the present the sanitarian will do well to continue to apply the general principles of control that are based on the justifiable assumption that the disease is a droplet infection, giving, however, increased attention to a point that is suggested by these experiments—namely, an infective period at the very earliest stages of the attack.

It would seem to be wise to give renewed emphasis to the importance of going to bed at the slightest indications of illness.

Abstract of the AMA Article, 1919

1377. Experiments to Determine the Mode of Spread of Influenza. Milton J. Rosenau. J. Am. M. Assn., Chicago, 1919, 73, 311.

Experiments to determine the mode of spread of influenza were carried out on Gallops Island. One hundred volunteers were mostly between 18 and 25 years, while a few were about 30. Pure cultures of Pfeiffer’s bacillus were administered to some of the volunteers but failed to produce the disease.

Large quantities of a mixture of 13 strains of the Pfeiffer bacillus were suspended and the suspension sprayed into the nose, eyes and throat of 19 volunteers. This experiment was also negative. Next 1 cc. of the mucous discharges of patienta was sprayed into the nostrils, throat and eyes, also without producing disease.

The blood from patients suffering from influenza was injected in 10 cc. quantities into each of 10 volunteers without producing disease. Ten volunteers were then brought into close contact with 10 patients and though the patients breathed and coughed into the faces of the volunteers no disease appeared.

Similar experiments were conducted at Portsmouth with the result that half of the volunteers came down with fever and sore throat caused by hemolytic streptococci. The author concludes that we are still ignorant of the true mode of spread of influenza. - P. G. H.

Abstract from Influenza: An Epidemiologic Study, 1921

These results with sleeping contacts form an interesting link in the chain of evidence started in 1918 by the U. S. Navy and Public Health Service, reported by Rosenau and McCoy, and others. These experimenters working in Boston and San Francisco carried out inoculation experiments on human volunteers.

The work in Boston, as reported by Rosenau, was carried on with 100 volunteers from the Navy between the ages of eighteen and thirty, most of them between eighteen and twenty-five; all of them entirely well, and except for a few controls, none having experienced known attacks of influenza previously.

First, suspensions of thirteen different strains of influenza bacilli, all from cases of influenza during the epidemic, were sprayed into the nose, eyes, and throat of nineteen volunteers. None of them took sick.

Next, secretions from the mouth, nose, throat, and bronchi of acute cases of influenza were collected, pooled, and without filtration sprayed into each nostril, into the throat during inspiration, and onto the conjunctiva of each of the ten volunteers.

None of them took sick. Some of this same material was filtered through a porcelain filter and administered in the same manner, with similar results.

One cubic centimeter of each type was administered to each individual. The interval between the time of collection and injection time was then decreased to one hour and forty minutes, the minimum time in which the material could be transferred from the hospital to the experiment station.

The same results were obtained. This time six cubic centimeters were administered to each individual. Finally, transfer was made directly with swabs from one individual's nose, throat, and nasopharynx to another in nineteen cases. None developed the disease.

Bibliography

Excerpt from Alternative Etiologies, Other Vaccines, in Public Health Report, Vol. 125, No. 1, January/February 2010, Supplement 3: Science, Microbiology, and Vaccines in 1918, p.33.

"Some Interesting Though Unsuccessful Attempts to Transmit Influenza Experimentally," in Public Health Reports, Vol. 34, No. 2, 10 January 1919, pp. 33-36.

"Diseases of the Respiratory System: Entry 1377. Experiments to Determine the Mode of Spread of Influenza. Milton J. Rosenau. J.," in Abstracts of Bacteriology, Vol. III, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company, 1919, p. 234.

Rosenau, M. J.- " Experiments by Volunteers to determine the Mode of Spreading Influenza," Med. Record, 1919, xcvi., p. 214.

Rosenau, M. J.— " Experiment to determine the mode of spread of influenza ," Jour. Am. Med. Ass., 1919, LXXIII, 311.

Warent T. Vaughan, M.D., Influenza: An Epidemiologic Study, in The American Journal of Hygiene, Pennsylvania: The New Era Printing Company, Monographc Series No. 1, 1921.

Rosenau MJ, Last JM. Maxcy-Rosenau preventative medicine and public health. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1980.

🌟 Most Engaging & Noteworthy Aspects of This History

📌 The Gallops Island & Angel Island Experiments: Failed Attempts to Transmit Influenza

🔹 The study involved 100 healthy U.S. Navy volunteers who had no prior history of influenza.

🔹 Researchers sprayed live flu bacteria directly into their noses, throats, and eyes—yet none got sick.

🔹 Volunteers shook hands, spoke at close range, and even allowed infected patients to cough in their faces—still, no flu cases developed.

🔹 Blood transfusions from flu patients were directly injected into volunteers—no transmission occurred.

📜 Why This Matters:

✔ Demonstrates the early struggles of medical science in understanding viral infections.

✔ Raises questions about whether the flu was truly bacterial or viral (a debate not settled until 1933).

✔ Highlights the limits of medical knowledge during the early 20th century.

📌 Dr. Milton Rosenau’s Unexpected Conclusion: "We Do Not Know What We Think We Know"

🔹 Rosenau was one of the most respected epidemiologists of his time.

🔹 He entered the experiment believing influenza was bacterial and could be spread through close contact or contaminated surfaces.

🔹 After months of failed transmission attempts, he reluctantly concluded:

🗣 "Perhaps, if we have learned anything, it is that we are not quite sure what we know about the disease."

📜 Why This Matters:

✔ Challenges the conventional wisdom of the time, forcing scientists to rethink influenza transmission.

✔ Demonstrates the humility of real scientific discovery, where even leading experts must admit uncertainty.

✔ Provides a compelling historical parallel to modern viral outbreaks (such as COVID-19), where initial assumptions about transmission can later be proven wrong.

📌 The Harvard University Influenza Study: A $50,000 Research Gift to Solve the Mystery

🔹 A private corporation donated $50,000 (equivalent to nearly $1 million today) to fund Harvard University’s research into influenza.

🔹 Led by Dr. Rosenau, this study investigated the causes, complications, and prevention of influenza.

🔹 Harvard medical students benefited from real-time research into the pandemic.

📜 Why This Matters:

✔ Highlights how private industry contributed to public health research in times of crisis.

✔ Demonstrates the growing role of academic institutions in medical research.

✔ Serves as an early example of pandemic funding and collaboration.

📌 The Role of U.S. Navy & Public Health Service in Influenza Research

🔹 The U.S. Navy and Public Health Service played a major role in trying to understand and contain the 1918 flu.

🔹 Military personnel were at high risk, as soldiers and sailors were constantly moving and living in close quarters.

🔹 The Navy’s quarantine stations on Gallops Island (Boston) and Angel Island (San Francisco) became experimental sites for testing flu transmission.

📜 Why This Matters:

✔ Reveals how pandemics disproportionately affect military personnel.

✔ Shows the early use of quarantine stations in infectious disease control.

✔ Provides insight into the military’s role in scientific research during crises.

📌 The Lingering Mystery: How Did the 1918 Flu Spread?

🔹 If the most contagious disease known at the time couldn’t be spread in a controlled environment, how was it transmitted in real life?

🔹 Later discoveries (post-1930s) confirmed influenza is a virus, not a bacterium.

Some modern researchers speculate that:

🔹 Viral shedding occurs before symptoms appear, making transmission experiments ineffective.

🔹 The immune system plays a larger role in transmission than previously thought.

🔹 Airborne transmission (through microscopic aerosols) was not yet understood in 1918.

📜 Why This Matters:

✔ Demonstrates the evolution of scientific understanding of infectious diseases.

✔ Shows why it took decades to fully understand influenza transmission.

✔ Provides a historical precedent for modern public health crises, including COVID-19.

📷 Noteworthy Images & Their Significance

📷 Dr. Milton Rosenau (circa 1910) – Highlights the prominent epidemiologist behind the groundbreaking study.

📷 Gallops Island Quarantine Station (Boston Harbor) – One of the main sites where influenza experiments were conducted.

📷 Angel Island Quarantine Station (San Francisco) – Showcases the West Coast counterpart to Gallops Island, where similar experiments were run.

📚 Relevance for Different Audiences

📌 🧑🏫 For Teachers & Students:

✔ Provides a compelling case study on early pandemic research and epidemiology.

✔ Highlights the scientific method in action, including failures and unexpected results.

✔ Connects to modern discussions on pandemic preparedness and misinformation.

📌 📖 For Historians & Public Health Researchers:

✔ Offers primary source evidence of early public health experiments.

✔ Sheds light on the military’s role in pandemic response.

✔ Demonstrates how medical assumptions can be wrong and need to evolve.

📌 🧬 For Genealogists & Family Historians:

✔ Provides insight into how the 1918 pandemic affected military personnel.

✔ Highlights medical practices and pandemic responses during ancestors’ lifetimes.

✔ A valuable contextual backdrop for researching relatives who lived through the pandemic.

🌟 Final Thoughts: A Groundbreaking Experiment That Raised More Questions Than Answers

📌 The Rosenau Experiment remains one of the most perplexing scientific studies in pandemic history.

✔ It highlights the difficulties of studying a rapidly spreading disease.

✔ It demonstrates the power of the scientific method—even when results are inconclusive.

✔ It reminds us that pandemics are complex, and scientific knowledge evolves over time.

📌 This collection of documents is a vital historical resource for educators, researchers, genealogists, and historians studying the 1918 flu pandemic and its long-lasting impact on medical science. 🦠💉