The Role of the American Library Association at Ellis Island: Providing Comfort and Education to Immigrants (1920)

📌 Explore the American Library Association's invaluable work at Ellis Island in providing multilingual books, educational resources, and a sense of community to immigrants during their time of detention.

The American Library Association's Work At Ellis Island

Relevance to Immigration Studies

This article, The American Library Association's Work at Ellis Island, provides an insightful and fascinating look into an often-overlooked aspect of immigration history—the role of libraries in the lives of detained immigrants at Ellis Island.

For teachers, students, genealogists, and historians studying the cultural and social impact of immigration in the early 20th century, this work offers a unique perspective on how the American Library Association (ALA) contributed to the well-being of immigrants by providing educational resources and comfort during their detention. The inclusion of multilingual resources and stories of personal engagement further adds to its value for anyone researching immigrant experiences or cultural assimilation at Ellis Island.

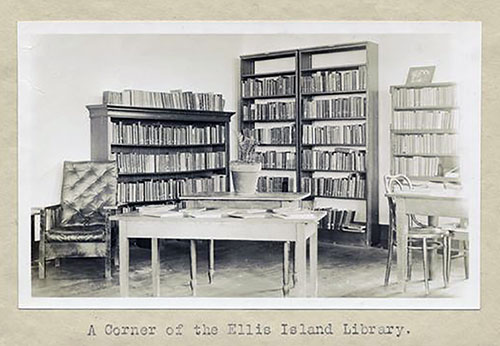

A Corner of the Ellis Island Library. New York Public Library #94675. GGA Image ID # 2195682319

The hospital at Ellis Island is one of the Federal Public Health Service Hospitals. Ellis Island is three islands joined together at one end by connecting bridges, like three teeth in a comb.

Numbers designate the three divisions, Island No. 1 being the headquarters of the immigration work proper—examination and detention quarters for the immigrants and administrative offices. Islands no. 2 and no. 3 contain the hospital buildings, where the number of patients averages from 150 to 475 at all times.

The library was moved about a month ago from a little room about twelve feet square to a ward at the end of Third Island. This is a bit remote for some patients to reach, but they are cared for in other ways.

The room is so lovely that we are only too grateful to the hospital authorities for moving us. It is about 25 by 55 feet, has windows on three sides, and has a magnificent view of the harbor with varied shipping. In the hot weather, it will be one of the choicest locations this summer.

We have four classes of patients in the hospital—the War Risk men, of whom there are only about 20 left, but who are responsible for our undertaking the work in the first place; the immigrants who are detained through illness contracted on shipboard or of longer standing, which may, if it does not yield to treatment, cause their return to the country of origin; Bolsheviki, or others, waiting for deportation; and many, many seamen, both foreign and American.

All receive precisely the same book service. There are six wards reserved for contagious cases, chiefly children, for whom we can do little. For the adults in these wards, we supply newspapers and magazines, and we also use the worn books that are not worth rebinding, such as the Grosses and Dunlap reprints. Everything left in these wards is burned when read.

The A. L. A. has placed about 500 books of fiction in the Red Cross house on Second Island, and these are read in the room and may be borrowed by both patients and employees for use outside.

Indeed, we wish the hospital employees to feel as free to use the library as the patients. However, I must confess that they have been primarily in the minority.

This is partly because we have been unable to keep the library room open in the evenings and partly because they have taken it for granted that it was for patients only and have yet to try to use it.

If we could convince them that it was their library too and that they were welcome to come and smoke and read in the evenings, the labor turnover, which is so appalling at present, might be lessened.

At present, except for one movie a week in the Red Cross house, they have no recreation and no place to sit except in the Red Cross house or their crowded dormitories. But we cannot provide both day and evening hours until we have more help (which means more money).

But to come back to the patients. In an immigrant hospital of this kind, we naturally have many races represented, and to meet their needs, we already have books in 23 languages and are still hunting for more.

We have a little rubber-tired wagon similar to a tee-wagon but stronger, with two shelves. With this, we make our rounds to the wards, 18 in all, visiting each ward twice a week so that every bed patient, as well as those able to walk about, may have a chance to get a book, and so far as possible, a book in his tongue.

I could find only six books in Arabic for an Arab patient. We have been fortunate in having regular weekly donations of Scandinavian newspapers from the American-Scandinavian Foundation, Spanish and French papers and magazines from the Foreign Department of the Hotel McAlpin, and all sorts from the American Foreign Language Paper Association.

These papers are invaluable in supplying material in languages in which we have not yet been able to get books, such as Czech, Slovak, and Yugoslavia, and in establishing friendly relations with a non-English-speaking person who is apt to assume when a book is offered that it is just another scheme to get money from him or that it is in English, which he cannot read.

When I make up my wagon to visit the immigrant wards, I always plan to carry at least two books of every language we have represented in the library collection and more of the more usual tongues to be prepared for all possible emergencies.

This usually fills the top shelf, and on the lower shelf, I put in my English books, with plenty of Western stories, a few good love stories, one or two histories and biographies, and a few books of travel, with maybe an arithmetic, a book on letter-writing, elementary chemistry and something on gasoline engines.

At first, I made the mistake of carrying all fiction, and that is, of course, still far in the lead in popularity, but the other books are much appreciated and are often grabbed with an exclamation such as "Why I didn't think you had such books in the library?"

Some of the immigrants read three or four languages, putting me quite to shame with their knowledge of literature. One Icelandic man in the hospital speaks seven easily—his English is perfect and without an accent.

Many foreigners are eager borrowers of our "beginning-English" books. I regret that it has not been possible to organize little classes of these and take advantage of their enthusiasm.

But after all, it is with the seamen on Third Island, where my room is located, that my interest at present is closest. When these men become convalescent, they naturally drift down to the library.

It has been a matter of great interest to the hospital authorities to see how much they read. Dr. Kerr, the chief medical officer of the Island, has spoken several times of the surprise he felt when he found that these "hardened old salts" would read book after book. He has commended the library very strongly for its therapeutic value in helping to keep the patients in a contented frame of mind.

And the young Americans—many more than I had sap-posed—were following the sea, simply reading book after book—always Western or sea stories first, gradually drifting to books on engines, navigation, and the like. We have even had several requests for cookbooks, which, after all, is not so strange when we consider that every ship must have its cook.

Our circulation last month was about 1300—about 600 in foreign languages. Since I should estimate the entire collection to be about 2500 to 3000 volumes, of which perhaps 700 or 800 are foreign, the books are well-used with the larger building up of the foreign collections and the rounding out of the English. We will probably be able to increase the circulation considerably.

We have several Russians who have read every Russian book. Our best Polish reader finished the Polish collection a month before his discharge, and some of the French have practically exhausted that collection.

There are several Spanish seamen there at present, and as a consequence, Spanish took the lead in the foreign languages this last month, with French second, Italian third, and Swedish fourth.

Most interesting is the story of the American lad of nineteen who has been helping us in the library. Ever since he became convalescent, which means during all the time I have been at work on the Island, he has voluntarily spent all his free time, both mornings and afternoons, in the library, charging and discharging books when I was making the rounds of the wards, putting them on the shelves, doing carpenter work and general tinkering, and making himself invaluable.

Last week, he came to me and said he was to be discharged on Saturday, and "My, but I shall miss these books," he said. I told him he wouldn't need to if he shipped on an American boat, for we were putting collections on every boat in the American merchant marine. He was interested at once.

"Is the — Line (plying between Canada and Florida) American or Canadian?" was the next question. I said I didn't know, but I thought it was Canadian. 'Well, I'm going for a job on an American line this time if I can get one. I won't go back to the — Line at all." And he didn't.

Last Wednesday, he came over to tell me that he had shipped on a U. S. Shipping Board vessel for China and that they had a library on board in charge of the steward, with Thursday set for the day to exchange books.

He feels that the books will help make the voyage better and more profitable for him, and it is because I have found so many other men on the Island just as keen to hear about the A. L. A. Libraries, many of them already know that I have to do what I can to make this present campaign a success.

I want to stay with Ellis even temporarily, but I can't work over there now with those Lots and then have the whole thing back on them at the end of a year because of a lack of funds to keep it up. So I've consented to turn over my place to someone else temporarily, and I'm off to the New York State headquarters at Syracuse to do what I can for my sailors.

I hope that someone else will be as intensely interested as I am in working on all the other points in the Enlarged Program. All of them are good and worthy of the finest kind of support. We can't afford to lose the impetus we got during the war and return to the old, easy-going, drifting ways of former days.

This personal description is one bit of A. L. A.'s work, requested from Miss Huxley to illustrate one phase of the more extensive work under Miss Caroline Jonas, from whom we hope to present an article descriptive of hospital service in and amended New York in a later Issue. Ed. L. J.

Huxley, Flounce A. "The American Library Association's Work At Ellis Island," in The Library Journal, April 15, 1920

Key Highlights and Engaging Content

The Library’s Role at Ellis Island:

The article highlights the establishment and relocation of the library at Ellis Island, emphasizing its crucial role in providing not only books but a space for recreation and refuge for immigrants awaiting processing.

The room, with its large windows and magnificent views of the harbor, became a sanctuary for immigrants and hospital patients alike. The library was not just a repository of books but a place that offered emotional comfort and an escape for individuals facing uncertain futures. 📚🏞️

Multilingual Resources and Cultural Sensitivity:

One of the most fascinating aspects of this article is the library’s multilingual collection, which was essential in serving Ellis Island's diverse population. The article reveals how the ALA ensured books were available in 23 languages to accommodate the wide variety of immigrants detained on the island.

The narrator’s efforts to provide books that were culturally appropriate and in various languages reflect the ALA’s dedication to helping immigrants feel valued and understood, bridging cultural gaps and alleviating loneliness. 🌍📖

The Human Connections and Personal Stories:

The article also weaves in personal stories that make the library’s work more meaningful. The account of an Icelandic man who spoke seven languages or the young American sailor who found solace in the books shows the therapeutic power of reading and how the library became a vital part of the daily life for many immigrants.

The story of the young American sailor who eagerly took on the role of a helper in the library is especially moving, highlighting the intergenerational and cultural exchanges that occurred even within the confines of Ellis Island. 👨⚖️📘

Engagement with the Immigrant Community:

The library staff made an effort to engage directly with the immigrant population, making rounds to the wards and distributing books in a variety of languages. This was not just about providing reading material—it was about humanizing the immigration experience.

This story exemplifies how libraries could function as educational tools as well as community-building spaces, offering comfort during an otherwise difficult and uncertain time for many immigrants. 🌟🚶♀️📚

The Library’s Impact on Patients and Staff:

A notable point of the article is the therapeutic value of the library, particularly among hospital patients, including the "hardened old salts" or sailors who seemed to surprise medical staff with their enthusiastic reading habits.

This reflection on the psychological impact of reading in a hospital environment underlines the importance of intellectual engagement in maintaining mental health during a stressful, uncertain period.

The library's work helped sustain the minds and spirits of both immigrants and staff, making the experience of Ellis Island more bearable. 🏥📘

Educational and Historical Insights

The article provides invaluable insight into the intersection of immigration and educational outreach during the early 20th century. For genealogists, it serves as a reminder that immigration was not only a physical transition but also an intellectual and emotional journey that was sometimes shaped by resources like libraries.

The A.L.A. Library’s efforts highlight how libraries contributed to cultural assimilation, language acquisition, and the well-being of immigrant populations during a time of great social upheaval. For historians, the article adds a nuanced layer to our understanding of Ellis Island, showing that the work done there was not only about detaining and processing immigrants but also about creating a space for personal growth and healing. 🏙️🌍

Final Thoughts

The American Library Association's Work at Ellis Island underscores the crucial role of libraries in immigrant communities. By serving as cultural sanctuaries, educational resources, and community hubs, libraries provided far more than books—they became a lifeline for many immigrants.

This article offers a rich resource for anyone researching the human side of immigration and the cultural integration that took place at Ellis Island. The A.L.A.’s efforts exemplify how education and empathy intersected in the immigrant experience, leaving a lasting impact on countless individuals. 📖💖

🔎 Research & Essay Writing Using GG Archives

📢 This is NOT a blog! Instead, students and researchers are encouraged to use the GG Archives materials for academic and historical research.

🔎 Looking for primary sources on Titanic’s lifeboat disaster? GG Archives provides one of the most comprehensive visual collections available today.