Ship Passenger Lists by Year of Voyage

Organized by Year of Voyage, the listings for Ship Passenger Lists of the Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archive typically include the date, vessel, route, and class for voyages that originated from or called upon a port listed.

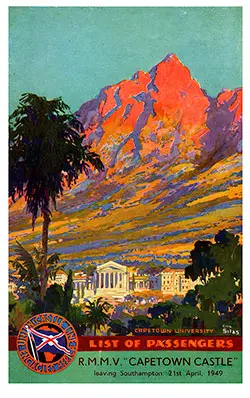

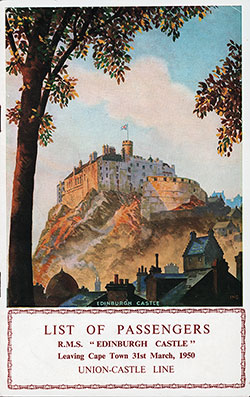

Coveted by collectors and genealogists, souvenir passenger lists often offered beautiful graphical covers and information not found in official manifests because they focused on the journey rather than the destination.

Very few "Souvenir" passenger lists exist for the 1870s and prior. The most common format for that period was likely the required passenger manifest, such as the 1878 manifest from the SS Pennsylvania.

Ship Passenger Lists 1800s

The year 1877 marked an important phase in transatlantic travel, with steamships solidifying their dominance over sailing vessels and immigration reaching significant levels. The City of Brussels, operated by the Inman Line, was among the era’s most advanced liners, reflecting the technological progress of the time. Castle Garden continued to be the gateway for thousands of immigrants arriving in America, shaping the country’s demographic and economic landscape.

The year 1878 was a period of expansion and modernization in transatlantic travel, with steamships like the SS Pennsylvania offering faster and more reliable service. Philadelphia emerged as a significant immigration hub, reflecting the broader trend of European migrants seeking industrial jobs beyond New York.

The year 1879 was a pivotal period in transatlantic travel, with steamship technology improving and migration patterns shifting due to economic opportunities in the United States. The SS California's voyage from London to New York underscores the continued reliance on British ports for migration. Meanwhile, Castle Garden remained central to the immigrant experience, serving as a gateway to America for thousands seeking a better life.

The year 1880 was marked by rapid developments in transatlantic migration, shipping technology, and industrial expansion in the United States. The SS City of Chester's voyage represents a period when steamship travel was reaching new levels of efficiency and reliability, allowing more people than ever before to cross the Atlantic. Castle Garden remained the principal processing center for immigrants, while major shipping lines like the Inman Line played a critical role in transporting passengers between Europe and the U.S.

This index of 1881 passenger lists showcases the diverse range of travelers who crossed the oceans, from wealthy passengers in luxurious saloon accommodations to impoverished immigrants in steerage. The inclusion of a rare steerage-class passenger list (SS Hohenzollern) is a highlight, as most records focus on first-class experiences. This collection primarily covers North American, European, Australian, and South African ports and is particularly sought after by genealogists and historians for its unique content.

The year 1882 saw continued growth in transatlantic migration, fueled by industrialization in the United States and economic difficulties in Europe. The RMS Servia, one of the most advanced steamships of its time, represented the future of ocean liner travel, with steel construction and electric lighting making voyages safer and more comfortable. The role of Castle Garden remained central to the immigrant experience, processing thousands of new arrivals each month and helping shape the demographic future of America.

The Castle Garden Passenger Lists for 1883 illustrate the diversity of travelers and the expansion of transatlantic routes during a period of major change in ocean travel. The contrast between luxurious saloon-class voyages and crowded steerage experiences highlights the economic divide in 19th-century travel. The continued presence of Scottish, Irish, and German emigrants on these passenger lists reflects broader migration trends that shaped the demographic landscape of the United States.

The Castle Garden Passenger Lists for 1884 provide a detailed view of transatlantic travel for elite passengers, primarily from Liverpool to New York. The dominance of saloon-class lists in this collection highlights the importance of wealthier travelers, business elites, and return passengers during this period.

The Castle Garden Passenger Lists for 1885 provide a fascinating look at European and transatlantic travel, highlighting both luxurious European routes (SS Westphalia) and major migration voyages (SS Ems). The records illustrate the continued dominance of German steamship lines, which played a critical role in transporting immigrants to the United States.

The year 1886 was a milestone year for transatlantic travel and immigration, with steamship travel at its height and record numbers of European immigrants arriving in the U.S.. The RMS Etruria was among the most prestigious ships of its time, representing the technological advancements in maritime travel. Meanwhile, one of the most significant events of the year was the dedication of the Statue of Liberty, which would soon become the defining symbol of hope for countless immigrants arriving in New York.

The Castle Garden Passenger Lists for 1887 primarily highlight upper-class and second-class travelers, documenting voyages from New York, Liverpool, Glasgow, Le Havre, and Boston. While the majority of transatlantic migrants traveled in steerage, these lists provide insight into the business elite, wealthy emigrants, and transatlantic professionals who traveled in saloon and second-class accommodations.

The Castle Garden Passenger Lists for 1888 reflect the diverse nature of transatlantic travel, from luxury saloon-class passengers on the RMS Umbria and SS Furnessia to steerage emigrants aboard the SS Lahn. The prominence of French Line (CGT) ships in this collection also highlights France’s growing role in transatlantic migration and business travel.

The Castle Garden Passenger Lists for 1889 provide insight into the evolving landscape of transatlantic travel, showcasing the growing diversity of travel classes and migration patterns. While steerage-class emigrants made up the majority of transatlantic passengers, this collection focuses on saloon, cabin, and second-cabin travelers, highlighting the increasing professional and middle-class migration from Europe to the U.S.

The Castle Garden / NY Barge Office Passenger Lists for 1890 offer a unique glimpse into the world of transatlantic travel, capturing the movement of wealthier business travelers, professionals, and middle-class emigrants, rather than the steerage-class passengers who made up the bulk of immigration at this time. The passenger lists in this index primarily cover European ports, including Liverpool, Bremen, Le Havre, and Glasgow, emphasizing the dominance of Cunard, Anchor, North German Lloyd, and French Line (CGT) in transatlantic travel.

The Castle Garden/Barge Office Passenger Lists for 1891 capture a critical moment in transatlantic travel, just before the opening of Ellis Island and major shifts in U.S. immigration policies. The dominance of saloon and cabin-class travelers in this collection highlights the growth of luxury and business travel, rather than the large-scale immigration that defined this era. This collection primarily documents saloon and cabin-class passengers, representing business travelers, professionals, and wealthier emigrants, rather than the steerage-class passengers who made up the majority of transatlantic immigration at the time.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1892 document a historic moment in U.S. immigration history, as Ellis Island became the primary processing center for new arrivals. This collection captures the diversity of transatlantic passengers, from wealthy saloon-class travelers to middle-class emigrants who could afford cabin accommodations. This collection features ships from Holland-America Line, Red Star Line, Inman Line, North German Lloyd, and the French Line (CGT)—all major carriers of European emigrants and business travelers.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1893 offer a valuable glimpse into transatlantic travel during a turbulent economic period, highlighting the various classes of passengers who crossed the Atlantic. The index showcases major European and American steamship lines, including North German Lloyd, Anchor Line, Cunard Line, and the American Line, with voyages departing from Glasgow, Liverpool, Southampton, and Genoa.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1894 capture a critical moment in transatlantic migration, documenting the movement of Scottish, German, and Italian passengers in both steerage and cabin classes. The rise of Southern European immigration, reflected in the SS Werra’s Naples departure, signals the shifting demographics of U.S. immigration during this time. This selection primarily includes transatlantic voyages between North America and Europe, with stops in key ports such as Glasgow, Bremen, and Naples. The inclusion of both cabin and steerage passengers provides insight into the social and economic divisions of the era.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1895 provide a rich historical snapshot of transatlantic migration and ocean liner competition, capturing both elite and working-class travel experiences. Several major European and American steamship lines are represented, including Cunard Line, North German Lloyd, Anchor Line, Red Star Line, and the American Line, with voyages departing from Liverpool, Southampton, Antwerp, Glasgow, and Bremen.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1896 highlight the continued evolution of transatlantic travel, showcasing the social and economic shifts in migration trends. This collection provides a diverse view of passengers, from wealthy saloon travelers aboard the RMS Germanic to second-class emigrants seeking better opportunities aboard the SS Paris.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1897 offer a diverse and insightful look into transatlantic migration, capturing the impact of Ellis Island’s temporary closure, the expansion of Canadian routes, and the increasing presence of American steamship companies. The steamship lines featured in this collection include Allan Line, Anchor Line, Hamburg-Amerika Line, and the American Line, with voyages between New York, Glasgow, Liverpool, Hamburg, Southampton, and Canada.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1898 showcase a year of significant geopolitical and technological change, as transatlantic travel remained a status symbol for the elite while also expanding to serve the growing middle class. At this time, Ellis Island was temporarily closed due to a fire, and immigrants arriving in New York were processed through the Barge Office (1897-1900).

The Ellis Island/Barge Office Passenger Lists for 1899 reflect a changing landscape in transatlantic and global ocean travel, with luxury travel growing alongside large-scale immigration. This collection features major transatlantic and global steamship lines, including Cunard Line, American Line, Holland-America Line, Dominion Line, and the Atlantic Transport Line, with routes connecting New York, Boston, London, Liverpool, Rotterdam, and Australian ports.

Ship Passenger Lists 1900s

The Ellis Island/NY Barge Office Passenger Lists for 1900 mark the end of an era, as Ellis Island reopened after years of immigration processing at the Barge Office. This collection captures a wide range of transatlantic and global voyages, from elite travelers aboard luxury liners to second-class emigrants seeking new opportunities in North America.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1901 reflect the changing nature of transatlantic travel, with immigration increasing, luxury travel expanding, and American steamship lines becoming more competitive with their European counterparts. This year’s collection features a diverse range of ports, including New York, Southampton, Bremen, Liverpool, Cherbourg, Boston, Glasgow, Queenstown (Cobh), Plymouth, Boulogne-sur-Mer, and Naples, reflecting the vast network of transatlantic migration and luxury travel.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1902 showcase the evolving landscape of transatlantic migration and high-class ocean travel, reflecting growing immigration, shifting destinations, and heightened competition among steamship lines. This collection includes voyages from premier steamship companies, including Cunard Line, White Star Line, Hamburg-Amerika Line, Norddeutscher Lloyd, and the Atlantic Transport Line, with Liverpool, Southampton, Hamburg, New York, Boston, and Philadelphia serving as key hubs.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1903 highlight the dramatic shifts in transatlantic migration and luxury ocean travel. The majority of voyages in this collection focus on transatlantic routes between Europe and North America, with ships departing from Liverpool, Glasgow, Bremen, Hamburg, Southampton, and Naples bound for New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. However, this year also includes a significant transpacific voyage (SS Siberia from Yokohama to San Francisco), reflecting the expansion of global steamship routes beyond the Atlantic.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1904 capture a pivotal year in transatlantic travel, reflecting record immigration levels, the rise of second-class travel, and increasing competition among luxury liners. This year also features a growing number of voyages to Boston and Philadelphia, as well as the presence of Holland-America Line, Red Star Line, and Atlantic Transport Line, highlighting the diversification of transatlantic shipping beyond British and German dominance.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1905 provide an extensive record of transatlantic and global ocean travel, showcasing the increasing demand for passenger services across multiple classes. This collection highlights voyages from major steamship companies, with routes connecting North America, Europe, and beyond. This year's passenger lists include notable first-class voyages, luxury liners, and an increasing number of European shipping lines competing for dominance in transatlantic travel.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1906 provide a snapshot of transatlantic migration, luxury travel, and growing competition among steamship lines. This collection includes passenger lists from multiple classes (first, second, and cabin), reflecting the increasing diversity of travelers. The rise of second-class travel is a key trend in this collection, showing a shift away from steerage-only migration toward more comfortable accommodations for middle-class travelers.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1907 capture a dynamic period of transatlantic and transpacific travel, with records showcasing voyages from major European, North American, and Mediterranean ports. These souvenir lists provide a unique glimpse into the migration trends, luxury travel, and competitive maritime industry of the early 20th century.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1908 offer an extensive record of transatlantic and transpacific voyages during a crucial year of mass migration, luxury ocean travel, and growing competition among steamship lines. This period was marked by rapid technological advancements, a booming economy, and increased competition among the world's leading steamship companies, particularly between Cunard, White Star, Hamburg-Amerika, Holland-America, and the American Line.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1909 capture a pivotal year in transatlantic and global ocean travel, highlighting the golden era of steamship competition, luxury travel, and mass migration. In 1909, the race for dominance among steamship lines was in full force, with Cunard, White Star, Hamburg-Amerika, and North German Lloyd competing fiercely to attract both elite travelers and immigrant passengers.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1910 showcase a world on the brink of major change. The last peaceful years before WWI saw steamship travel reaching its peak in luxury, migration, and industrial expansion. This collection highlights the increasing prominence of European migration to the U.S., Canada, and South America, as well as the continued competition among major shipping lines like Cunard, White Star, Hamburg-Amerika, and Norddeutscher Lloyd.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1911 offer a valuable glimpse into global transatlantic migration, luxury travel, and increasing maritime competition as the world neared the Titanic era. This year was particularly significant in the history of ocean travel, as it was the final full year before the Titanic disaster in April 1912. A notable trend in 1911 was the increasing prominence of second-cabin travel, reflecting a growing middle class able to afford transatlantic crossings in comfort.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1912 document a pivotal year in maritime history, forever defined by the sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 14–15, 1912. This year marked the peak of luxury ocean travel, with ships like Titanic, Lusitania, and Mauretania dominating transatlantic routes. It was also a time of mass migration, as thousands of European immigrants continued to arrive in North America seeking better opportunities.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1913 document a significant period in transatlantic and global steamship travel, as the industry adjusted to new safety regulations introduced after the Titanic disaster of 1912. This year saw increased safety measures on ocean liners, continued mass migration to North America, and the rise of Canadian ports as immigration entry points. The lists highlight major shipping lines, such as Cunard, White Star, Hamburg America, and Holland-America, which continued to dominate transatlantic travel.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1914 reflect a transformative year in global ocean travel, as the outbreak of World War I in late July abruptly altered transatlantic shipping routes and priorities. Early in the year, steamship travel continued as usual, with luxury liners, immigrant transports, and leisure cruises operating regularly. However, once war broke out on July 28, 1914, between the European powers, the nature of passenger travel changed dramatically.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1915 reflect the continued impact of World War I on transatlantic travel. By this time, ocean liners operated under extreme caution, as the war had intensified at sea. German U-boats posed a significant threat to both military and civilian vessels, particularly in the North Atlantic. The sinking of the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915, by a German submarine marked a turning point in wartime maritime policy and had a chilling effect on passenger travel.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1916 provide a fascinating glimpse into transatlantic travel during one of the most dangerous years of World War I. With the war at its peak, passenger and cargo ships alike were under constant threat from German U-boats, leading to fewer transatlantic voyages and heightened security measures for those that did sail.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1917 offer a rare glimpse into ocean travel during the most critical year of World War I. By this time, the war had reached a turning point, and transatlantic travel was increasingly dangerous due to German unrestricted submarine warfare. Many of the great ocean liners that once carried thousands of passengers across the Atlantic had been requisitioned for wartime service, either as troop transports or hospital ships.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1918 reflect a critical phase of World War I, when transatlantic civilian travel was nearly nonexistent, and the majority of ocean liners were used exclusively for war transport.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1919 reflect a pivotal year in transatlantic travel as the world transitioned from the chaos of World War I (1914–1918) to a post-war recovery period. With the Armistice signed in November 1918, the year 1919 saw the gradual resumption of civilian passenger travel, as ocean liners shifted from military service back to commercial operations.

Ship Passenger Lists - Interwar Years 1920-1939

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1920 represent a critical period of transition in transatlantic and ocean liner travel. Following the devastation of World War I (1914–1918) and the post-war adjustments of 1919, 1920 marked the return of large-scale civilian migration. However, this year was particularly significant due to new immigration restrictions and the recovery of the steamship industry.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1921 capture a pivotal year in transatlantic and ocean liner travel, marked by the implementation of the U.S. Emergency Quota Act of 1921. This law dramatically restricted immigration, particularly from Southern and Eastern Europe, changing the composition of passenger lists and reducing the overall number of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1922 reflect a period of major transformation in transatlantic travel, as strict immigration laws and shifting priorities in passenger services shaped ocean liner operations. Following the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which limited the number of immigrants allowed into the U.S., steamship companies continued adjusting their services to attract tourists, business travelers, and middle-class passengers rather than large numbers of third-class immigrants.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1923 reflect the continuing transformation of ocean liner travel, as immigration restrictions remained in place and steamship companies focused on business, tourism, and upper-class travel. The Quota Act of 1921 and the upcoming Immigration Act of 1924 further reduced mass migration to the United States, compelling shipping companies to adapt their strategies.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1924 reflect a new era in ocean liner travel as the United States Immigration Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act) came into effect. This law severely restricted immigration, particularly from Southern and Eastern Europe, and marked a dramatic decline in third-class steerage passengers. With mass migration slowing down, ocean liners shifted their focus to cabin-class travel, luxury tourism, and business travelers.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1925 highlight a changing landscape in transatlantic and international ocean travel. With U.S. immigration still restricted under the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, steamship lines continued their shift away from mass immigration transport to luxury travel, business voyages, and cruising.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1926 reflect a transforming era in transatlantic and global ocean travel. With immigration to the U.S. continuing to decline due to restrictive laws, passenger liners shifted toward leisure, tourism, business, and elite travel. Notably, this year saw high-profile celebrities and business figures traveling on Cunard and other major liners, furthering the glamorization of ocean liners as the preferred mode of travel for the wealthy and influential.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1927 highlight the continued shift in ocean travel from immigration to tourism, business, and elite travel. The listings provide valuable insights into transatlantic, transpacific, and luxury cruise trends during the year. Notably, Germany, Italy, and the United States maintained strong transatlantic liner competition, while Cunard, White Star, and Canadian Pacific continued to dominate the luxury and business-class market. Tourist-class accommodations became more common, making ocean travel more accessible to middle-class travelers.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1928 provide insight into the evolving landscape of transatlantic and transpacific travel as ocean liners became more focused on tourism, leisure, and comfort rather than immigration. The emergence of tourist-class cabins and shopping promenades on ships reflected a growing middle-class demand for sea travel. While Germany and Italy expanded their fleets, the U.S. and Britain remained dominant in transatlantic luxury travel.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1929 capture a pivotal year in ocean travel, highlighting the rise of luxury, the expansion of tourist-class travel, and the growing influence of German and American liners. This was a golden era for transatlantic crossings, with ships becoming floating palaces of comfort, shopping, and entertainment. However, 1929 was also the year of the Wall Street Crash in October, an event that would soon affect passenger traffic, ship construction, and the entire ocean liner industry.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1930 showcase a year of transition in ocean travel, as the effects of the Great Depression began to take hold. While the early months of 1930 still reflected the luxury and grandeur of the late 1920s, by the latter half of the year, economic strain started impacting passenger numbers, ship construction, and industry competition.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1931 reflect the growing effects of the Great Depression on transatlantic travel. While luxury liners still operated, passenger numbers in first-class declined, and tourist and third-class accommodations expanded. Cruising gained popularity, with voyages focusing on exotic destinations rather than simple transatlantic crossings.

The 1932 Ellis Island Passenger Lists reflect a year of continued economic challenges, as the Great Depression deepened and heavily impacted transatlantic travel. While ocean liners remained the primary method of long-distance travel, the effects of the economic downturn shifted passenger demographics, with an emphasis on tourist-class and economy accommodations. Cruises also gained traction, with ships offering voyages beyond standard transatlantic crossings.

The 1933 Ellis Island Passenger Lists document another year of economic struggles during the Great Depression, which continued to reshape the steamship industry. Transatlantic travel declined, first-class accommodations dwindled, and more ships focused on tourist and economy-class passengers. However, new ships and services emerged, cruises remained popular, and certain luxury liners continued their prestige despite financial hardships.

The 1934 Ellis Island Passenger Lists reflect a year of transition for the transatlantic steamship industry. The effects of the Great Depression continued to reshape travel patterns, leading to a greater emphasis on tourist-class accommodations and a decline in first-class luxury travel. However, 1934 also marked a major milestone in maritime history with the merger of Cunard Line and White Star Line, one of the most significant developments in the history of ocean travel.

The 1935 Ellis Island Passenger Lists reflect a dynamic year in ocean travel, marked by the continued dominance of European luxury liners, the growing influence of American steamship lines, and the introduction of the RMS Normandie, a ship that would redefine transatlantic crossings. The effects of the Great Depression were still evident, with an emphasis on tourist-class travel, while celebrity passengers and aviation pioneers added glamour to ocean travel.

The 1936 Ellis Island Passenger Lists showcase a pivotal year in transatlantic and global ocean travel, marked by intense competition among ocean liners, technological advancements, and shifting travel trends. The year saw the rise of the RMS Queen Mary, an intensifying rivalry between France’s Normandie and Germany’s Bremen and Europa, and the growing role of the United States in the steamship industry.

The 1937 Ellis Island Passenger Lists provide a fascinating look into the golden age of ocean travel, with luxury liners, elite voyages, and expanding global routes. This was a year of intense competition between the great transatlantic liners, with the Normandie, Queen Mary, Bremen, and Europa leading the way. Additionally, political tensions in Europe began influencing passenger travel, with N**i Germany using its liners for propaganda and Italy’s shipping industry growing in strength.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1938 showcase a collection of souvenir passenger lists from major steamship lines, preserving a snapshot of transatlantic and other long-distance maritime travel in the late 1930s. What makes this collection interesting is its reflection of ocean travel just before World War II, including the presence of German, British, Italian, French, and American ships, many of which would soon be repurposed for war efforts.

The Ellis Island Passenger Lists for 1939 represent a crucial turning point in maritime travel history, capturing the final months of civilian transatlantic crossings before World War II disrupted commercial shipping. The souvenir passenger lists in this collection provide a glimpse into the world of luxury liners, immigrant travel, and the final crossings before many of these great ships were requisitioned for war service.

The 1940 passenger lists represent a dramatic shift in ocean liner travel as World War II had engulfed Europe, making transatlantic crossings perilous. Unlike previous years, when travel was dominated by leisure cruises, immigration, and business voyages, 1940 was defined by evacuations, war refugees, and emergency relocations.

Post World War 2 Passenger Lists 1946-1954

The 1946 passenger lists mark the resumption of civilian ocean travel after World War II, as ships once used for troop transport and wartime service returned to commercial operations. This year represents a transitional period where ocean liners began carrying post-war migrants, refugees, and individuals displaced by the war, many of whom sought a new life in North America, Australia, and South Africa.

The 1947 passenger lists reflect a significant shift in transatlantic and global ocean travel. The world was transitioning from wartime service back to commercial and civilian maritime travel, with passenger liners once again focusing on luxury, tourism, and post-war migration. This year marked the revival of grand transatlantic voyages, with Cunard Line, United States Lines, and Orient Line leading the resurgence of passenger shipping.

The 1948 passenger lists reflect the post-war revival of ocean travel, as transatlantic voyages became more frequent, luxurious, and accessible. The world’s largest and most prestigious ocean liners, such as the RMS Queen Elizabeth, RMS Queen Mary, SS America, and RMS Mauretania, dominated the routes between Europe and North America, while Holland-America, Orient Line, and CGT-French Line contributed to global routes.

The 1949 passenger lists highlight the continued growth and evolution of ocean travel in the post-war era. With international economies stabilizing and migration still at high levels, transatlantic and global passenger voyages flourished, led by dominant lines like Cunard, United States Lines, Holland-America, Italia Line, and Canadian Pacific Line. While ocean liners remained dominant, the rise of Tourist Class, increasing student travel, and new migration patterns shaped the industry.

The 1950 passenger lists mark a pivotal moment in transatlantic and global ocean travel, as ocean liners remained the dominant mode of transportation, but faced growing competition from commercial aviation. This period saw a continued rise in migration, an expansion of Tourist Class, and the post-war boom of luxury travel. This year was one of the last great years for ocean liners before air travel began overtaking them as the preferred method of crossing the Atlantic.

The 1951 passenger lists capture a critical transition in transatlantic and global travel as ocean liners continued to be the dominant mode of transport, but commercial aviation was rapidly growing as a competitor. During this period, luxury travel thrived, migration surged, and Tourist Class expanded, making transatlantic crossings more accessible to middle-class travelers. This year also saw a rise in post-war migration, with significant voyages between Europe and North America, and continued migration from Italy, the UK, and Canada.

The 1952 passenger lists highlight a transformative year in ocean travel, with the maiden voyages of the SS United States, the continued expansion of Tourist Class, and new routes connecting North America, Europe, and South America. This year saw one of the last peak years for ocean liners before commercial aviation gained a stronghold in the transatlantic travel market. The Passenger Lists for 1952 document a turning point in maritime history, as air travel rose, Tourist Class expanded, and the SS United States entered the scene.

The 1953 passenger lists document an era in which ocean liners remained a vital force in global travel despite the continued rise of commercial aviation. This year saw luxury travel flourish, the expansion of the Tourist Class, and migration routes connecting Europe, North America, and South America. This was one of the last golden years of ocean liner travel, as, by 1958, commercial jets would make transatlantic crossings by air the new standard.

The 1954 passenger lists mark the final full year of Ellis Island’s operation as an immigration station, making this an especially significant year for transatlantic travel and migration history. The last immigrant, Norwegian merchant seaman Arne Peterssen, was processed at Ellis Island on November 29, 1954, bringing an end to an era of mass migration through the station.

The 1955 passenger lists document an important transitional period in maritime history. While iconic ships like the Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth, and SS United States continued to make prestigious voyages, the growing influence of air travel was beginning to challenge the supremacy of ocean liners. These voyages highlight the lasting appeal of transatlantic travel while also signaling the industry's impending shift toward cruising and leisure travel rather than mass migration.

The passenger lists of 1956 document a maritime industry that was at a crossroads. While ocean liners remained a popular method of travel, their dominance was being challenged by advancements in aviation. Cunard, a leader in transatlantic crossings, continued to provide services for both migrants and tourists, with the Ivernia catering to the growing number of immigrants traveling to Canada and the Mauretania maintaining the traditional transatlantic route.

The 1957 passenger lists reflect an era of transition for ocean liner travel, as the airline industry was rapidly advancing, drawing more passengers away from traditional sea voyages. However, transatlantic liners like the RMS Queen Elizabeth continued to serve thousands of passengers, particularly those who sought the luxury and nostalgia of sea travel. Many ships still carried migrants, particularly to North America and Australia, but leisure and business travel were increasingly dominant.

All Digitized Lists of Passengers for 1954 Available at the GG Archives. Listing Includes Date Voyage Began, Steamship Line, Vessel, Passenger Class and Route.

All Digitized Lists of Passengers for 1954 Available at the GG Archives. Ships included the Queen Mary and Saxonia.

All Digitized Lists of Passengers for 1954 Available at the GG Archives. Ships included the Nieuw Amsterdam.

All Digitized Lists of Passengers for 1954 Available at the GG Archives. Ships included the Carinthia.

Recap and Summary of the "Ship Passenger Lists by Year of Voyage" Index Page

Overview

The Ship Passenger Lists by Year of Voyage page from the Gjenvick-Gjønvik Archives serves as a comprehensive historical resource for researchers, genealogists, and maritime enthusiasts. It organizes passenger lists chronologically, covering voyages from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, detailing migration patterns, notable ships, and key historical events that influenced transatlantic and global travel.

What makes this collection particularly valuable is its breadth and diversity, capturing everything from early steamship crossings to the golden age of ocean liners, wartime transport, and the gradual transition to air travel. The passenger lists, often presented as souvenir documents, highlight class distinctions, major shipping lines, and significant global migration trends.

Key Highlights and Noteworthy Voyages

1. 19th-Century Transatlantic Migration & Industrialization (1800s–1890s)

- Castle Garden Era (1855–1891): Early immigration processing at Castle Garden in New York saw millions of European migrants arriving via steamships, many fleeing economic hardship, war, or famine.

- Early Steamship Innovation: Ships like the City of Brussels (Inman Line, 1877) and RMS Servia (Cunard Line, 1882) showcased the transition from sail to steam-powered travel.

- Diverse Ports & Routes: Major routes included Liverpool, Hamburg, and Le Havre to New York and Philadelphia, reflecting shifting migration trends.

- Introduction of Luxury Travel: By the late 19th century, passenger lists documented saloon (first-class) travelers, reflecting the emergence of transatlantic leisure voyages.

- Notable Voyages:

- SS Pennsylvania (1878) – Highlighted Philadelphia’s growing role in transatlantic migration.

- RMS Etruria (1886) – One of Cunard’s premier liners, known for speed and luxury.

- Statue of Liberty Dedication (1886) – Arriving passengers in late 1886 may have witnessed the unveiling of Lady Liberty.

2. Ellis Island & the Peak of Transatlantic Migration (1892–1914)

- Ellis Island Opens (1892): This period marked the peak of mass immigration from Europe, with millions processed at Ellis Island.

- Rise of North German Lloyd & White Star Line: German shipping companies competed with British lines, introducing more luxurious ocean liners.

- RMS Titanic Disaster (1912): The sinking of the Titanic marked a pivotal moment in maritime safety, influencing future ship designs.

- Notable Voyages:

- SS City of Chicago (1883) – Illustrates the growth of U.S.-bound passenger traffic from Liverpool.

- SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse (1901) – A record-breaking German liner, ushering in a new era of speed and comfort.

- RMS Lusitania (1915) – The sinking of the Lusitania during World War I intensified tensions between Germany and the U.S.

3. Wartime Ocean Travel & Post-War Migration (1914–1945)

- World War I (1914–1918): Many civilian ocean liners were converted into troop transports.

- Interwar Period (1920s–1930s): The golden age of luxury liners, with ships like the RMS Queen Mary and Normandie dominating the Atlantic.

- The Great Depression (1930s): Economic struggles led to fewer first-class travelers, increasing the focus on tourist-class travel.

- World War II (1939–1945):

- Ocean liners were requisitioned for troop transport and refugee evacuations.

- Notable wartime voyages included the SS Manhattan (1940) evacuating civilians from Lisbon.

4. The Post-War Ocean Liner Boom & The Rise of Air Travel (1946–1957)

- Return to Civilian Travel: Passenger liners resumed transatlantic crossings, facilitating post-war migration to North America and Australia.

- Expansion of Tourist Class (1950s): Affordable tourist-class cabins made ocean travel accessible to middle-class travelers.

- SS United States (1952): The fastest ocean liner ever built, reflecting the U.S. attempt to dominate the North Atlantic.

- Ellis Island Closure (1954): Arne Peterssen became the last immigrant processed at Ellis Island before its closure in November 1954.

- Air Travel Overtakes Ocean Liners (1957+): The decline of ocean liner travel began, with commercial jets replacing transatlantic crossings.

Key Takeaways from the Index Page

- Historical & Genealogical Value: These passenger lists provide a window into migration history, documenting family journeys, economic trends, and global mobility.

- Evolution of Ocean Travel: The index captures technological advancements, from early steamships to grand luxury liners and war-time conversions.

- Global Impact of Maritime Travel: Passenger records illustrate how ocean liners shaped economies, influenced global migration, and adapted during crises like wars and economic downturns.

- The Decline of Ocean Liners (1950s): The rise of aviation in the late 1950s led to the gradual decline of passenger ships, marking the end of an era for transatlantic crossings.

Conclusion

The Ship Passenger Lists by Year of Voyage index is an essential resource for maritime and immigration history, offering a detailed timeline of global passenger travel from the 19th century to the mid-20th century. The collection highlights major migrations, technological advancements, and cultural shifts, providing an invaluable reference for researchers, historians, and family historians tracing their ancestors' journeys.