Medical Inspection Of Immigrants At The Port Of Boston- 1914

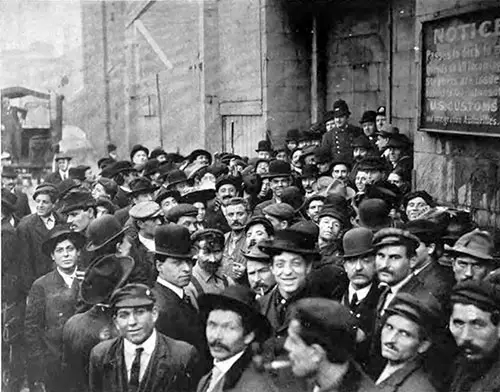

Boston Immigrant Landing Station - Recently Arrived Immigrants circa 1912. The New Immigration, 1912. GGA Image ID # 147a2c2b8c

By J. Nute, B.S., M.D. Boston, P. A. Surgeon. United States Public Health Service. U. S. Immigration Station, Boston, Massachusetts.

While the above heading is the subject this evening, it generally applies to all aorta of the United States. The story of immigration is as old as the history of the United States; with specific qualifications, it is the history of this country. While laws in the early days provided for the restriction of inanimate goods, more or less unwritten and written laws restricted human beings from certain localities, which finally grew into organized law to protect the community.

For example, the Quakers were not welcome in the land of the Puritans, and Virginia gradually closed the door to redemption. Our institutions have been founded by, supported by, and in turn supported by aliens and their descendants. The first rule of national life is self-preservation. As immigration still has a vital role in America's national life, it must be carefully scrutinized to admit the desirable.

The medical aspect of immigration was brought to public notice about 1824 when New York City attempted to levy a head tax on all foreign passengers arriving in that city; later, in 1847, a similar act was passed by the state. This money was intended to support an immigrant hospital. The courts declared it unconstitutional in both cases because the power to regulate commerce was vested in Congress and not in any state.

For many years, each state dealt with the problem of limiting the entry of diseases and aliens as best they could. Of course, this wasn't easy, owing to the ease of passing from one state to another. This was probably the first restrictive policy that was actively started. Still, of course, the country's earlier history showed that economic pressure tended to restrict newcomers to those nearest the region's race, language, and ideals.

When the Federal Government supervised the matter in 1882, it adopted a general rule to reject those who suffered from physical defects liable to make them public charges, note being made of insane, idiots, and persons unable to take care of themselves. In 1891, it further extended this law to include those suffering from loathsome or dangerous contagious diseases.

In 1903, the most radical step was taken when the Government placed a fine of $100 on the steamship company, in addition to exclusion, for each case of a loathsome or dangerous contagious disease that could have been detected by competent medical inspection at the time of embarkation.

In 1907, the United States extended the law to exclude people with epilepsy, feeble-minded people, persons who have been insane within five years or have had two or more attacks of insanity at any time previously, tuberculosis (meaning tuberculosis of the lungs, intestinal tract, or the genitourinary system), or those suffering from such mental or physical defect which may affect the ability of the alien to earn a living.

At the same time, idiots, imbeciles, and tuberculosis were placed in the $100 fine class. In 1891, Congress turned the work of medical inspection over to the Marine Hospital Service (now the Public Health Service). This Service has published definite rules for the medical examination of aliens, which, if followed, ensure a uniform system of inspection and records at all ports of entry.

Whether an immigrant belongs to the excluded class is a function of the immigration officials. This is often confusing to many, for one must understand that the Immigration Service is a bureau of the Department of Labor, and the Public Health Service is a bureau of the Treasury Department.

Hence, the two Bureaus work together. The medical officer's certificate constitutes the legal evidence upon which the immigration officials base their action, in mandatory eases, and in other cases, consider the certificate to affect the ability to earn a living or likely to become a public charge.

Seldom does the alien suffer from a medical judgment that is too harsh. All things considered, he gets the best end of the doubt, for the rules require the certificate to be based on conclusive evidence. For example, a pulmonary tuberculosis case cannot be certified unless a microscopical slide showing the bacilli can be demonstrated.

Briefly, the law divides all defectives into three classes and makes no distinction between the cabin and steerage passengers. United States citizens are exempt from examination but may be called upon by immigration officials for satisfactory evidence of citizenship.

Class A. Mandatory exclusion because of definite specified diseases such as idiocy, imbecility, feeble-mindedness, insanity, epilepsy, tuberculosis, loathsome, or dangerous contagious diseases.

Class B. Aliens not classified under Class A but present some defect or disease affecting the ability to earn a living, such as hernia, heart disease, inadequate nutrition, varicosities, presenility, specific conditions of the nervous system, chronic joint disorders, observed impaired vision, and tuberculosis of the skin, glands, and joints.

Class C aliens that present defects or diseases of less seriousness must be sure of the information of the immigration officers that they may pass intelligently on with ease.

Every passenger carries an identification card to prevent any alien from passing by without examination by a doctor. In the cabin, this card is punched as each alien passes the medical officer so that the inspector can tell at a glance whether or not he has been seen. As the immigration inspectors are on the alert, they usually return to the doctor any alien who presents any unusual physical or mental appearance, even if his card is punched.

To prevent any delay, the doctor notes a slight abnormality, such as a burn scar on the face, and gives the alien a slip noting the condition and stamped "Special Medical Passed." The steerage usually examined onshore is checked by attendants to prevent any oversight. At Ellis Island, an attendant stamped the steerage passengers' inspection cards in ink.

In the law, contagious means communicable, and loathsome contagious means those whose presence excites abhorrence and are essentially chronic, such as favus, ringworm of the scalp, leprosy, and venereal diseases. Trachoma, hookworm, and amoebic dysentery may illustrate dangerous contagious diseases.

The examination method varies depending on the local conditions. The medical officer must exercise care and tact to accomplish this without undue annoyance to travelers or traffic delays. Before the inspection, two sources of information are at hand: the manifest sheet and the ship surgeon's report. How reliable this information is depends on the type of men filling out the forms.

When one considers that nearly all immigration is carried in foreign ships crewed by foreign officers, it requires experience in dealing with them to estimate the value of their reports. As far as possible, all inspections should be made in daylight under artificial light. Certain diseases involving different hues or alterations in the skin cannot be noted accurately.

The medical examination is divided into two parts: primary and secondary. In the primary, the examiner's efforts are directed toward segregating from those presented those suspected of having disease, defect, or abnormality of any kind to enable the healthy to proceed without unnecessary delay.

Secondary: systematically inquiring into the signs and symptoms in those turned aside to determine a diagnosis and proper certification. The alien may be detained for any reasonable observation period required to complete the diagnosis and, if necessary, hospital treatment provided.

Primary inspection is conducted on an even, level surface so that the passenger may not be tempted to look where he is stepping. Care is taken against crowding to maintain an evenly spaced line and carry as little baggage as possible.

The examiner stands in a position to secure as even illumination as possible. One must avoid direct sunshine in the face or reflected from the water.

To facilitate the work, the line should turn right before the examiner to secure a good view of both sides and back with the least effort.

Standing with the light falling over his shoulder, he begins his study of the alien at about twenty feet distant. Starting with the feet at that distance, the eye gradually rises from the feet to the head without effort as the alien draws near. The examiner then proceeds systematically to examine the line as it approaches. The character of the gait or other defects of the lower extremities will attract attention, such as flat feet, nervous disorders, deformities, abnormalities, joint diseases, or artificial legs.

As the glance sweeps upward, the immigration physician may note undue prominence of or about the groins and hands as they furnish essential evidence of general physical development, diseases of the respiratory and vascular system, disordered or impaired nutrition, defective mentality, nervous and contagious diseases, besides local defects and deformities. The abdomen was noticed for undue protrusion, ascites, splenic enlargement, pregnancy, and abdominal tumors in general.

The chest is examined for asymmetry, undue prominence, defective development, and the back for evidence of spinal disease and deformity. The neck is surveyed for goiter, abnormal pulsations, enlarged glands, tumors, and malformations.

The head is examined for abnormalities such as unusual shape deformity, disproportion, and asymmetry affecting the bones of the face and skull; this includes any signs of disease of the ears and the skin. The oral and ocular membranes are an index for anemia. At the same time, the scalp and beard are scrutinized for evidence of ringworm, favus, or other infection. By this time, the alien had arrived close enough for the eyes to be taken into close detail, and the lids had everted to detect trachoma.

A feminine voice may further confirm the suspicion of arrested sexual development, which has been aroused by noting the absence of a beard and the peculiar wrinkles about the upper lip, a shaky voice often found in alcoholics, scanning speech or hoarseness make us at once turn off at case for more detailed examination.

Not only sight but also touch and smell play a part. The hand against the forehead gives an idea of the presence of fever, while sight takes in conditions about the month. Response to a simple question provides an index of hearing and mental reaction. At the same time, the sense of smell may arouse suspicion of uremia, ozaena, favus, foul discharge from the ear, abscesses, or ulcers concealed by clothing.

Associated with this, the examiner acquires a habit of noticing unusual conduct, bearing, language, peculiar facial expressions, and emotional outbreaks. Febrile changes are constantly watched for signs of exanthemata. In infants, one may note one of the most apparent signs of respiratory changes by watching the movements of the alae nasi muscles.

Defective vision is often detected by squinting, a desire to keep in the proximity of accompanying persons, a tendency to look down while walking, avoiding the gaze of the examiner, or indecision or confusion in the sense of orientation when obliged to make a sudden change in the direction of his course.

A general impression is formed when the immigrant is face-to-face with the examiner. It has either been so favorable that the alien is passed at once, or one may have noted something to cause his detention.

The above gives a general idea of what observation shows on the preliminary examination. The secondary examination is the regular medical procedure to confirm a diagnosis or pass the alien.

To the casual visitor, it may seem a common condition and tend to justify the criticism of a writer that I quote from a Boston newspaper.

The immigrants simply file past them, and they look hard at them as hard as they can, and that is about all they do. If they are looking for any particular one, they switch him off for further examination and do the same if their suspicions are aroused. They are very clever at detecting skin and eye diseases and do their best work in that line. They don't see all, and thousands get by them.

Diseases like tuberculosis of the lungs are constantly coming in against the law; all except the very advanced cases were getting in. Still more important are the mental disorders, the feeble-minded, and the insane, which are rarely detected."

Owing to the critic's lack of knowledge of immigration law and experience in the practical side of the examination and its results, the above is a good description of the impression made.

It is of the same value as the medical student's opinion who, after attending a few large surgical clinics, said that all there was to surgery was "Cut it off or cut it out."

As a matter of fact, there is much more to it than the casual visitor ever hers unless he is willing to spend plenty of time in careful investigation of the subject from all sides.

Knowledge of racial types and their peculiarities is essential, for without this, many normal persons would be detained. Hence, ethnology plays a vital part.

Since the days of laboratory and other aids to diagnosis, we have tended to lose sight of the value of observation and what it may tell us until we are reminded of it by some expert like the late Professor Fits of Harvard. It is interesting to note that over seventy-five years ago, Robert Ferguson, in a lecture before the students of King's College, London, stated, "That there is a right and wrong method of observing is evident since mankind has always observed but rarely discovered."

In fact, one can safely state that almost no serious organic disease can hold an individual without stamping some evidence of its presence upon the patient's appearance, evident to the eye or hand of the trained observer.

It must be borne in mind that owing to certain limitations. Immigration inspection is a sieve and not a dam. Also, medicine is not a science like mathematics. It would be decidedly unfair to certify a person on suspicion. Hence, it is a wise provision in the regulations that calls for definite evidence and gives the alien the right of appeal.

To those who look on from the outside, it may seem as if little is accomplished if one considers the fact that the stream of men, women, and children passing in line is composed of a body of individuals from whom the physicians in the employ of the steamship companies have already endeavored to eliminate the physical and mentally unfit, it may be a matter of surprise to know that about 1.5 percent, of the total number of immigrants arriving at the ports of the United States, have been certified for physical or mental defects that would place them in one of the classes which either rendered deportation mandatory or required the alien to submit satisfactory proof that his disability will not make him a public charge.

The following paragraphs will describe some conditions met to show how experience in this work is necessary to avoid the mistake of confusing racial characteristics with pathological conditions.

It takes considerable experience to know what constitutes a healthy color in a given race. A healthy Gypsy might readily be suspected of having Addison's disease, a healthy Greek of suffering from malarial cachexia or malignant disease. A normal West Indian Negro sometimes has the peculiar pallor suggestive of tuberculosis, and the temperate Alpine mountaineer often dilated capillaries resembling those seen in chronic alcoholics. Seasickness may readily leave harmful effects for some days, and the pallor and weakness suggest some severe constitutional disease.

Pulsating blood vessels in the neck are often caused by fright, increasing the heart's action. One can readily note that all or nearly all immigrants pale before the doctor in high nervous tension, for they believe the battle is nearly over with the medical officer.

This is not their first medical examination. They have seen others weeded out before leaving. In contrast, during the voyage, weird tales of all sorts have been poured into their ears about what may happen, with all the local color and exaggeration characteristic of human nature.

Irritation of the conjunctiva caused by certain occupations involving exposure to smoke, dust, or heat, such as ironworkers, bakers, coal miners, and line workers, may cause chronic inflammation and scar formation of the lids simulating an old incompletely cicatrized trachoma.

The face of a muscular, able-bodied Italian peasant is often so devoid of fat and muscle tissue that, at first sight, one would think that the whole body is thin and undeveloped.

The complexion of the Slavish peasant woman would be suspicious of chlorosis if possessed by a Scandinavian or English woman of the same class. On the other hand, the red cheek of the Scandinavian would arouse the thought of a hectic flush if seen in the Polish woman.

The excitability of the southern Italians and the Hebrews is well known. It is easy to get excited by their almost maniacal actions. The stolidity and indifference of the Slavs would suggest melancholia if presented by the Hebrews.

An Englishman's sanity would be questioned if, on slight provocation, he manifested the external manifestation of emotion that would occur in the Sicilian. The German girl takes her examination seriously, and her sanity would once be suspected if she saw the exact reason for light remark and laughter as the girl from Ireland.

Some races are incredibly emotional, others slow, and it is impossible to pick the abnormal unless the normal is known. In short, in determining mental conditions by inspection, the first essential is to determine the individual's race or type and to have a good knowledge of his racial characteristics. To the trained examiner, the facial expression, attitude, mannerisms, and dress convey an expression of understanding.

It would be difficult for an examiner not familiar with the Syrian peasant type to form an opinion of his mental caliber from his appearance or attitude alone. A few questions will determine reaction and orientation. If nothing is noted from this, the alien may be allowed to pass. Otherwise, he is held for a complete mental examination.

Under the present law and facilities, it is impracticable to consider every alien a possible mental defect and subject him to complete examination unless there were some signs of mental disorder on primary inspection.

With the feeble-minded, facial expression and attitude are valuable indexes except in the high-grade types, where they are negligible. It is a matter of judgment and experience of the examiner (based upon the normal) to decide how much lower the suspect is on the mental scale, considering all the factors of race, previous environment, and education.

Due to the lack of agreement among experts on where the normal ends, The term mental instability, psychopathic tendency, or constitutionally inferior can be referred to a class whose mental organization is of the weakest yet showing no definite mental symptom at present, would go on normally in primitive surroundings. Still, under slight stress, such as being found in a new country with disappointments, its strange language and customs become mentally disordered.

Inveetigatoni, who has carefully studied the subject, agrees that the medical inspection is no farce. Examiners with years of experience in the service have seen a marked increase in efficiency due to experience and increased facilities. It is imperfect, but it is being improved as fast as Congress grants authority and facilities. There are still many loopholes, and any attempt to seal them is naturally fought bitterly by those interested in keeping an open gate.

Newspaper or magazine articles on the subject are rarely tactful but rather sentimental fiction with just enough facts to give a good story foundation.

Every time a defective is admitted, it induces many more to try. If the public were truthfully informed, the country would receive a better physical and mental type of immigrant. In turn, the immigrant would or could have better treatment and protection.

It has been estimated that out of the alien head tax of $4.00, about twelve cents pays the art of the present inspection. If this is true, the medical department is undoubtedly not draining the public treasury.

The work is hazardous and requires men of good physique. Furthermore, they must be interested in the subject to pay close attention to their work. In the busy season, the constant standing and mental concentration tend to produce breakdown, and there is always the chance of contracting contagious diseases.

Medical Inspection of Immigrants

Owing to the recent agitation concerning immigration, this timely subject will bear careful reading. A review of the Immigration Service's annual reports shows that the most critical function of the immigration inspection lies in the medical examination. If an alien has a sound body and mind, he is not likely to do much harm.

A careful appraisal of our human imports is a serious matter requiring thought. Doubtless, more aliens are held and appeals taken for medical reasons, directly or indirectly than for any other reason.

Dr. Nute has broad experience in immigration work and a chance to see all sides, having been stationed on the Canadian border, at Ellis Island, N.Y., and at the port of Boston. He shows that undesirables have been attracted to this country; as communities grew, restrictions followed just as naturally against the aliens as against the foreign goods in the trade market.

Among the early adventurers were persons sent to America to serve out penal offenses, escape prosecution, and suffer from Wanderlust. Among the latter were many types that undoubtedly today would be recognized as mental defectives. Later on, those who had acquired settlement and had defective relatives were naturally anxious to have the defective relative at hand, mainly when American institutions gained the reputation of dealing more kindly with the inmates than the home asylums.

It is essential to understand that it has only been since 1903 that a financial penalty has been placed upon the steamship companies and that the alien is returned to the port of embarkation of his hometown. Also, there is always the appeal, hence the chance of a good gamble, as the ship has to return to Europe in the natural course of events. It has only been since 1907 that the feeble-minded have been mandatorily restricted.

Microscopical evidence must be present to certify certain conditions, like Tuberculosis, gonorrhea, favus, ringworm, etc. Any physician thus can understand how many incipient tuberculous persons may be admitted. According to the law, tuberculosis refers only to the lungs, genitourinary, and intestinal tracts. Persons suffering from Tuberculosis of the bones, joints, skin, glands, etc., may be landed. Persons with pulmonary Tuberculosis can be landed according to certain departmental decisions.

Like most other laws, immigration law has an exception for nearly every rule, and the alien with money and influence may utilize it to his advantage. The doctor never admits an alien, nor does he ever exclude one; that is the function of immigration officials.

Those who have traveled can readily realize the difficulties of cabin inspection, which often has to be made after dark, with poor light, and even in daylight in cold and stormy weather, someplace has to be sought that may not delay the ship or passengers. Doing this without slowing traffic, without inconveniencing passengers, who are often nervous, tired, and irritable after a long journey, who resent being asked personal questions, certainly requires tact.

Observation has taught these examiners a great deal, both in a knowledge of human nature and the practical recognition of diseased conditions. The spectacular linework is about all there is to the visitor. Still, he rarely follows behind the scenes and learns what happens to those who enter detention rooms. The most challenging work is often between ships when eases must be carefully recorded after due examination, which carries the hard work of any hospital examining room.

The mental examination is a different matter than any institution has to face. Here, the examiner must pick out the defectives from the mixed stream flowing past. After picking out a suspect, the doctor receives no aid from the alien's relatives or friends. Instead, all sorts of pressure will be borne to discredit the examiner.

The number of people working in Boston has markedly increased during the past year. New lines have entered, but the type of immigrant has changed. Not many years ago, most of Boston's immigrants came from Northern Europe and the British Isles. Today, southern and eastern Europeans predominate, and emigration begins from Turkey, Asia, and Persia.

Boston sadly needs a proper immigrant station, both for the protection of the public and in fairness to the detained immigrants. The present quarters are inadequate in every way. It does not require much of a rush of traffic to fill it, which causes many to be detained on shipboard until room can be made by either landing or deporting those detained on Long Wharf.

One should remember that detained aliens are not felons but human beings waiting to prove their right to land or waiting for the ship's sailing to return them to their homes. Boston is fortunate to have a well-trained medical staff. Still, the best carpenter cannot build much of a house with a jackknife. It is only due to the vigilance of these doctors that severe outbreaks of diseases have not occurred.

As a result of much injudicious talk in some newspapers and magazines, a false situation has been created, either by those who do not understand or those who are prejudiced against restriction.

Suppose every charitable institution, prison, or hospital supported in any part by public funds would report to the Immigration Service or in an annual report every inmate who is a public charge or who is seeking free aid. In that case, the taxpayers might learn something not hitherto realized.

There is only one reason for restricting immigration: protecting American institutions. There are many reasons for laxity: cheap labor, foreign commercial companies' traffic products, and a cheap vote easily controlled.

The feeble-minded problem is one of the most serious, for it is more open to dispute and less likely than the insane to become a public charge. Many forms of insanity are curable and at least usually recognizable. Still, the feeble-minded are the more dangerous, as they never play the normal in life's competition and often go for years or life unrecognized.

The best remedy is honest enforcement of the law—make every public office holder seeking to land a defective alien enter their name as a sponsor in the public records, give the medical department more authority and better facilities, and divide work better so that efficiency may not be diminished by speed, even if more medical officers are required, and lastly, have a more precise understanding on the part of the public that has to pay the bill.

Every alien should be required to show the United States that he is clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to land in this country instead of requiring the United States constantly to be on the defensive.

The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Thursday, April 23, 1914. a Journal of Medicine, Surgery and Allied Sciences. Published at Boston, Weekly, by the Undersigned. Papers for Publication and All Other Communications for the Editorial Department Should Be Sent to the Editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 809 Paddock Building, 101 Tremont Street, Boston. All Reprint Orders Must Be Sent in Writing to the Editor on or Before the Day of Publication.

Why You Should Read This Article on Medical Inspection of Immigrants at the Port of Boston (1914)

For teachers, students, genealogists, family historians, and public health researchers, this article provides a crucial historical perspective on immigration inspection in the early 20th century. It details the rigorous medical examinations immigrants faced upon arrival at Boston, one of America’s busiest ports, and highlights the evolution of public health policies and immigration restrictions.

Key Insights from the Article:

1. The Role of Boston in U.S. Immigration History

- Boston was a major entry point for Northern, Western, and later Southern and Eastern European immigrants.

- The article explores how immigration laws evolved, from early state-level restrictions to federal oversight in 1882.

- The Public Health Service and U.S. Immigration Service worked together to ensure immigrants were physically and mentally fit to enter the country.

2. The Medical Examination Process: Identifying the Unfit

- Immigrants were classified into three groups:

- Class A: Mandatory exclusion for conditions like insanity, epilepsy, tuberculosis, and contagious diseases.

- Class B: Those with physical defects that could impact their ability to work.

- Class C: Minor conditions that required documentation but did not bar entry.

- Every immigrant—whether in steerage or first-class—was required to undergo a medical inspection.

- Inspectors looked for physical deformities, contagious diseases, and mental disorders, often using quick observational techniques.

3. The Challenges of Mental Health Screening

- Mental illnesses such as feeblemindedness, epilepsy, and insanity were difficult to detect in short examinations.

- The Binet-Simon intelligence test was beginning to be used to assess immigrants for mental deficiencies.

- Some conditions, like mild cognitive impairments, could be missed or mistaken for cultural differences, making the process controversial.

4. The Struggles Between Public Health and Economic Interests

- Steamship companies resisted stricter health screenings to avoid financial losses from rejected passengers.

- The Public Health Service had limited resources—medical officers worked under extreme conditions with minimal facilities.

- Boston’s immigration station was overcrowded, causing delays and forcing immigrants to remain onboard ships until space was available.

5. The Public Debate on Immigration Restrictions

- Critics argued that the inspection process was too lenient, allowing contagious diseases and mental illness to enter the U.S.

- Others believed it unfairly targeted certain ethnic groups, particularly immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe.

- The article emphasizes that immigration restrictions were not about discrimination, but rather about protecting American public health and institutions.

Why This Article Matters for Immigration & Public Health History

📖 For genealogists and family historians: This article helps contextualize the experiences of ancestors who immigrated through Boston and the challenges they faced.

📖 For educators and students: It provides a detailed look at early 20th-century public health policies, making it a valuable resource for studies in history, immigration, and medical ethics.

📖 For public health researchers: It demonstrates the origins of modern disease control and immigration health screening, offering a historical case study on quarantine policies, disease detection, and mental health evaluations.

🚢 This article is an essential read for anyone who wants to understand how medical inspections shaped immigration, public health policies, and the lives of those who passed through America’s ports!