James P. Moody: Titanic's Youngest Officer and Witness to Disaster

📌 Explore the life and final voyage of James Paul Moody, Sixth Officer of the RMS Titanic. Discover firsthand accounts, official reports, and rare images that bring his role—and the tragedy—to life for students, historians, and genealogists alike.

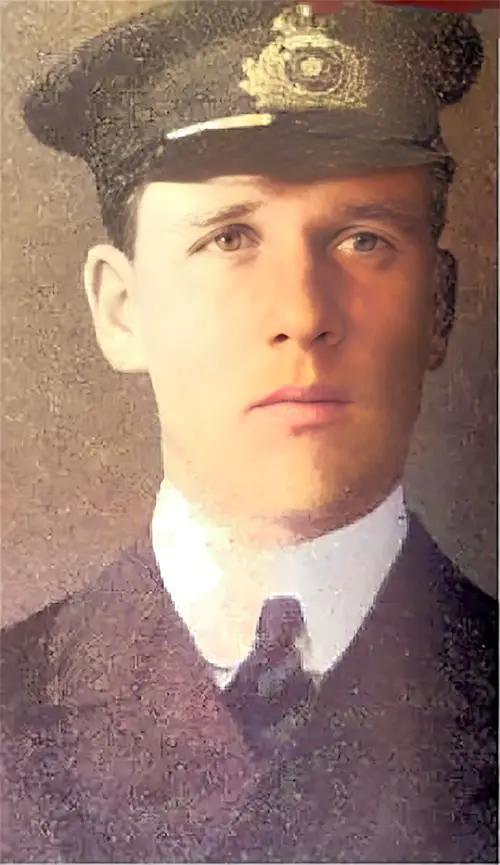

James Paul Moody, Sixth Officer on the RMS Titanic circa 1910. Mr. Moody Did Not Survive the Tragedy and Was Only 24 at the Time of His Death. GGA Image ID # 17046f0308

🔍 Review and Summary:

A Young Officer’s Final Watch: James P. Moody and the Titanic Disaster

This compelling biographical feature on James Paul Moody, Sixth Officer aboard the RMS Titanic, offers a richly detailed look into one of the youngest and most courageous crew members aboard the ill-fated ship. For educators, students, and history enthusiasts, this article provides a powerful narrative gateway into the personal dimensions of the Titanic tragedy—connecting facts, emotion, and context. 💔🌊

At just 24 years old, Moody was the junior-most officer aboard the Titanic—and, notably, the only officer to perish in the disaster. The story draws from two primary historical sources—Wreck of the Titanic and the British Inquiry Report—providing both a personal and official lens into the events of April 14–15, 1912.

James Moody Fast Facts

- Full Name: James Paul Moody

- Date of birth: 21 August 1887

- Place of birth: Scarborough, North Yorkshire, England

- Marital status: Single

- Crew position: Titanic's Sixth Officer

- Date of death: 15 April 1912

- Cause of death: Unconfirmed; body never recovered

- Formerly Chief Officer of the SS Caprera

Excerpt from WRECK OF THE TITANIC – p. 45-46

Not only was the Titanic tearing through the April night to its doom with every ounce of steam crowded on, but it was under orders from the general officers of the line to make all the speed of which she was capable.

This was the statement made by J. P. Moody, a quartermaster of the vessel and helmsman on the night of the disaster. He said the ship was making twenty one knots an hour, and the officers were striving to live up to the orders to smash the record.

“It was close to midnight,” said Moody, “and I was on the bridge with the second officer, who was in command. Suddenly he shouted, ‘Port your helm!' I did so, but it was too late. We struck the submerged portion of the berg.”

As nearly as most of the passengers could remember, the Titanic, sliding through the water at no more speed than had been consistently maintained during all of the trip, gracefully slid a few feet out of the water with just the slightest tremble. It rolled slightly; then it pitched.

The shock, scarcely noticeable to those on board, drew a few loungers over to the railings. Officers and petty officers were hurrying about. There was no destruction within the ship, at least not in the sight of the passengers.

There was no panic. Everything that could be seen tended to alleviate what little fear had crept into the minds of the passengers, who were more apprehensive than the regular travelers who cross the ocean at this season of the year and who were more used to experiencing those small quivers.

Not one person aboard the Titanic, unless possibly it was the men of the crew, who were working far below, knew the extent of the injuries it had sustained. Many of the passengers had taken time to dress, so sure were they that there was no danger.

They came on deck, looked the situation over and were unable to see the slightest sign that the Titanic had been torn open beneath the water line. When the passengers' fear had been partly calmed and most of them had returned to their staterooms or to the card games in which they were engaged before the quiver was felt, there came surging through the first cabin quarters a report, that seemed to have drifted in from nowhere, that the ship was sinking.

How this word crept in from outside no one seems now to know. Immediately the crew began to man the boats. Then came the shudder of the riven hulk of the once magnificent steamship as it receded from the shelving ice upon which it had driven, and its bow settled deeply into the water.

James Paul Moody Shown Wearing the Junior Officer's Uniform of the White Star Line circa 1911. GGA Image ID # 170478f17d

Excerpt from LOSS OF THE STEAMSHIP " TITANIC.", p.88-89

The foregoing evidence establishes quite clearly that Capt. Smith, the master; Mr. Murdoch, the first officer; Mr. Lightoller, the second officer; and Mr. Moody, the sixth officer, all knew on the Sunday evening that the vessel was entering a region where ice might be expected; and this being so, it seems to me to be of little importance to consider whether the master had by design or otherwise succeeded in avoiding the particular ice indicated in the three messages received by him.

At 6 p. m. Mr. Lightoller came on the bridge again to take over the ship from Mr. Wilde. the chief officer (dead). He does not remember being told anything about the Baltic message, which had been received at 1.42 p. m. Mr. Lightoller then requested Mr. Moody, the sixth officer (dead), to let him know "at what time we should reach the vicinity of ice," and says that he thinks Mr. Moody reported "about 11 o'clock."

Mr. Lightoller says that 11 o'clock did not agree with a mental calculation he himself had made and which showed 9.30 as the time. This mental calculation he at first said he had made before Mr. Moody gave him 11 o'clock as the time, but later on he corrected this, and said his mental calculation was made between 7 and 8 o'clock, and alter Mr. Moody had mentioned 11.

He did not point out the difference to him and thought that perhaps Mr. Moody had made his calculations on the basis of some "other" message. Mr. Lightoller excuses himself for not pointing out the difference by saying that Mr. Moody was busy at the time, probably with stellar observations.

It is, however. an odd circumstance that Mr. Lightoller. who believed that the vicinity of ice would be reached before his watch ended at 10 p. m., should not have mentioned the fact to Mr. Moody, and it is also odd that if he thought that Mr. Moody was working on the basis of some "other" message, he did not ask what the other message was or where it came from.

The point, however. of Mr. Lightoller's evidence is that they both thought that the vicinity of ice would be reached before midnight. When he was examined as to whether he did not fear that on entering the indicated ice region he might run afoul of a growler (a low-lying berg) lie answers: "No, I judged I should see it with "sufficient distinct ness" and at a distance of a "mile and a half, more probably 2 miles."

RMS Titanic Sixth Officer, James P. Moody

The foregoing evidence establishes quite clearly that Capt. Smith, the master; Mr. Murdoch, the first officer; Mr. Lightoller, the second officer; and Mr. Moody, the sixth officer, all knew on the Sunday evening that the vessel was entering a region where ice might be expected.

The Loss of the Steamship Titanic, Report of a Formal Investigation into the Circumstances Attending the Foundering on April 15. 1912. Of the British Steamship "Titanic." of Liverpool. After Striking Ice in or near Latitude 41° 46' N, Longitude 50° 14' W, North Atlantic Ocean, as Conducted by the British Government. Presented by Mr. Smith of Michigan, 20 August 1912.

🧲 Most Engaging Content Highlights:

💬 Moody’s Firsthand Recollection

“Suddenly he shouted, ‘Port your helm!’ I did so, but it was too late.”

This reconstructed quote from Moody paints a vivid and chilling picture of the seconds before the Titanic struck the iceberg. His presence on the bridge during impact makes this one of the most gripping moments in the article.

📜 Inquiry Report Insights

Moody was not just a passive observer—he actively calculated when the ship might enter the ice field, estimating it to be around 11 p.m. The inquiry excerpts show how Moody’s estimation diverged from other officers’, revealing missed opportunities and internal miscommunications that may have influenced the tragedy's outcome.

🕯️ Calm Before the Panic

The understated early moments after the collision—when passengers felt only a slight tremble—contrast hauntingly with what followed. Moody’s behind-the-scenes involvement in manning the lifeboats (before giving his own place away) deepens our appreciation for the heroism shown by junior officers.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images:

🧥 Moody in Uniform, 1910 and 1911

"James Paul Moody, Sixth Officer on the RMS Titanic circa 1910."

"James Paul Moody Shown Wearing the Junior Officer's Uniform of the White Star Line circa 1911."

These images are invaluable teaching tools. They offer visual connections to the real individuals behind historical events, helping students and genealogists alike to personalize the past. Moody’s youthful appearance underscores the tragedy of his loss and the human cost of the Titanic disaster. 📸🧍♂️

🎓 Relevance for Educational and Research Use:

For Teachers and Students:

This article is a strong secondary source ideal for:

🔹 Essay citations and classroom discussions on decision-making, duty, and maritime history.

🔹 Critical thinking activities comparing first-person accounts with official reports.

🔹 Cross-disciplinary lessons connecting math (calculating ice field timing) and history.

💡 Encourage students to explore the GG Archives when researching ocean travel or composing essays on Titanic crew members. The original documents and illustrations provide depth and authenticity beyond textbook summaries.

For Genealogists:

The article is useful for tracing individuals in ship service records and understanding the hierarchical structure of ocean liner crews in the early 20th century.

For Historians and Enthusiasts:

The blend of primary source material, official inquiry transcripts, and biographical context offers a layered, nuanced portrayal of a key—but often overshadowed—Titanic figure.

🧠 Final Thoughts:

James P. Moody’s legacy reminds us that courage is not measured by rank. His actions in the final hours—helping passengers, performing calculations, and remaining at his post—offer a story of quiet heroism amid chaos. This article is more than a biography; it’s an invitation to understand the Titanic not just as a tragedy, but as a human story of duty, youth, and sacrifice.

🌟 Use the GG Archives to enrich your next project, essay, or family research journey—because history lives in the details.