📖 Hope for a Generation: How the National Youth Administration Reshaped America’s Workforce

📜 Discover how the National Youth Administration (NYA) provided jobs, education, and training to young Americans during the Great Depression. This 1938 WPA report explores the NYA’s impact on youth employment, democracy, and social mobility. Essential reading for educators, historians & genealogists!

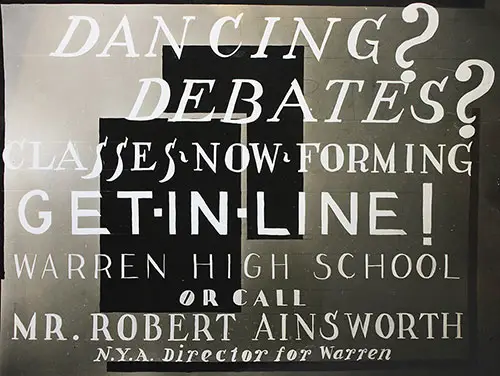

National Youth Administration Advertisement, c. 1939. This Photograph Depicts a Poster Advertising the National Youth Administration’s Programs, Which Included Dance and Debate, at Warren High School in Warren, Massachusetts. National Archives and Records Administration, NAID: 7351387. GGA Image ID # 2226f84947

📜 Introduction to the National Youth Administration (1938)

📖 "Building a Future for Youth: The National Youth Administration’s Role in the Great Depression"

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was one of the most significant New Deal programs aimed at addressing the youth unemployment crisis during the Great Depression. Established in 1935 as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the NYA provided job training, financial aid, and employment opportunities to millions of young Americans, helping them transition from school to the workforce.

This 1938 introduction to the NYA presents a comprehensive overview of its mission, achievements, and challenges. The foreword by Charles W. Taussig, chairman of the National Advisory Committee, provides an insightful analysis of the youth crisis in America, highlighting the economic instability, lack of education, and job shortages that plagued the younger generation.

For teachers, students, historians, and genealogists, this document is essential reading, offering:

✅ A firsthand account of the NYA’s efforts to combat youth unemployment.

✅ A deep dive into the social challenges faced by young people during the Great Depression.

✅ An exploration of government intervention in education and workforce training.

✅ A discussion of democracy, civic responsibility, and economic reform for youth.

Through government records, personal testimonies, and economic data, this historical document captures the spirit of Roosevelt’s New Deal and its attempt to secure the future of America’s youth.

Authors' Acknowledgments

This Book Originated in the Desire of the National Advisory Committee of the National Youth Administration for an independent survey of the activities of the NYA. Much of the information comes from first-hand observation in the field by one of the authors during the first four months of 1938 while temporarily engaged as a consultant to the National Advisory Committee.

In addition, we were granted free access to the files of the National Youth Administration and have made use of assembled data hitherto unpublished.

We are indebted, first of all, to Miss Thelma McKelvey, Director of the Division of Reports and Records of the National Youth Administration. Without the aid of her efficiency and intelligence and generous contribution of time, we could not have assembled much of the material that is in this book.

She and the members of her staff—Miss Mina Gardner, Mrs. Miriam Naigles, Mrs. Anita Day, and Miss Phyllis Scully—were helpful throughout and worked overtime to compile most of the data for the Appendix.

We are indebted also to Mr. Aubrey Williams, Mr. Richard R. Brown, Mr. David R. Williams, Mr. W. Thacher Winslow, Mr. John H. Pritchard, Dr. Mary H. S. Hayes, Mrs. Mary McLeod Bethune, and other members of the national NYA staff. We found them all engagingly frank in answering our questions and helpful in many other ways.

The regional directors, State directors, and many of their assistants, all of them already overburdened with work, have been extremely co-operative. We are grateful to all of them. Our thankful appreciation extends also to the hundreds of work project supervisors and the many members of the faculties of high schools and colleges who generously gave us their time and interpretations.

In this book we have attempted to give a panoramic picture of the NYA. Necessarily we have made some appraisals. They are strictly our own and should not be construed as those either of NYA officials or of any member of the National Advisory Committee.

B. L. and E. K. L.

Washington, May 8, 1938.

Foreword

By CHARLES W. TAUSSIG

Chairman of The National Advisory Committee of The National Youth Administration

If we are to consider as normal the years of the present century prior to the Great War, the entire generation which we today call "Youth" was born into an abnormal world. Greeted by a world war or the economic aftermath, they have known only a condition of social and economic instability.

Unprecedented post-war agricultural prosperity was quickly followed by collapse and dire distress. A few years of a riotous industrial boom, with all the attendant luxuries and banalities, were followed in 1929 by an economic crisis, from which we are now only hesitatingly commencing to emerge.

While we in the United States have been going through our own gyrations, our youth have seen the rest of the world tom by wars and revolutions. They have seen age-old governments crack up and be replaced by a variety of dictatorships.

American youth of today never knew the norms by which we judge the passing show. It is difficult for adults to understand the point of view of young people. We draw comparisons between present-day chaos and what we called normal some years back.

Youth know only chaos. With all the progress that has been made in our educational technique, much of it is still based on a world which no longer exists, and which has never existed for the younger generation.

Youth, in an effort to throw off the non-essentials and inadequacies of a system that prepares them for a life they have no opportunity to live, frequently discard the fundamentals of a good life. Integrity, spirituality, and a reasonable moral code are sometimes sacrificed.

On the other hand, hardship and suffering have developed in them a social consciousness that did not exist in previous generations. The amenities of life are no longer taken for granted. Today young people have once more become explorers, explorers in a world in which even their elders fail to recognize familiar landmarks, a world in which many a landfall has proved but a mirage.

With some justification, youth suspect the older generation of having worshiped false gods. Rightly or wrongly, they feel we have made a "mess of things/' The very system which we know as Democracy is subjected by youth to a cruel analysis. Vendors of gilt substitutes find willing converts to political and social creeds that are destructive to much that this Nation stands for.

Now, if ever, we must invoke our cardinal principles of free thought, free speech, and free education. Under the proper direction and leadership, our youth can and will develop a more definite and hopeful philosophy of life. Unless we educate the youth of today to function intelligently in a modem Democracy, democratic government is doomed.

Who can view the political, social, and economic changes in the world without looking to our own Democracy, even with its acknowledged shortcomings, as a haven of hope? To reinforce and perfect our system of government, we will require a leadership and an electorate far more intelligent and responsive than we have had in the past. We must remember that in less than a decade the group which we now designate as "youth" will control the destiny of this Nation.

Youth are dissatisfied, and with much justification. They are sentient, restless, and explosive. Unless we can give them the opportunities which they demand, they will seek a way for themselves that may endanger the very fundamentals of our liberties.

Their demands are not unreasonable. They desire an opportunity to cam a living; to marry at mating age; to attain education; to understand the principles and functions of our government They ask only a willingness on our part to consider them fellow-citizens of a great Democracy.

This in broad terms is what is called "the youth problem." In my judgment the following specific deficiencies in our national life have created this problem:

- There are not jobs enough to take care of the youth who need them and want them.

- Our educational system is not adequate, in size or character, to prepare multitudes of youth for the work opportunities that are available.

- Nationally speaking, there is not equal opportunity for education. Vast areas of the United States have inadequate educational systems. There are not enough free schools to take care of the youth population, and millions of youth and children are too poor to attend free schools and colleges even where they exist.

- There is a gap measured in years between the time a youth leaves school and the time he finds a job. During this period society completely abandons him. Most of our criminals are to be found in this social no-man's land.

The National Youth Administration was created in an attempt to find a solution or a partial solution for these four shortcomings in our social and economic life.

It is of importance that the reader of this book keeps in mind the basic philosophy of our American approach to this problem. The problem is not unique to the United States. It exists in most countries throughout the world. But an American solution must be predicated on the maintenance and reinforcement of the family unit. In totalitarian states, by contrast, the community and family are subordinated to a regimented nationalism.

Our American philosophy neither prevents a national approach to the problem nor puts undue emphasis on sectionalism at the expense of national purpose and national unity. On the contrary, equalizing opportunities within our communities and bolstering the more backward communities strengthen the Nation as a whole in the only way it can be strengthened in a Democracy.

On August 15, 1935, the National Advisory Committee of the National Youth Administration held its first meeting. Mr. Harry Hopkins, Administrator of the Works Progress Administration, within which organization the National Youth Administration functions, addressed the conference. A few excerpts from his talk will illustrate the official point of view at the commencement of this new adventure in applied Democracy:

It is awfully easy to make a speech about youth; how they have been neglected and the difficulties and disadvantages which have come to them through unemployment. When you try to put somebody to this and to be specific, definite, and precise as to what we are going to do, then it gets a little complicated. Our other student aid things are pretty simple.

You say to the University President: "Pick out the boys and girls wno are broke. Put them to work and give them a benefit." That is easy. But, when you get to some of these other problems on a national basis, it isn't so simple.

I have given this a great deal of thought and I have nothing on my mind to offer as a solution to our problems, and I know of no one else who has anything to offer resembling a satisfactory program for young people. I want to assure you that the government is looking for ideas, that this program is not fixed and set, that we are not afraid of exploring anything within the law.

On the same occasion, Mr. Aubrey Williams, the Director of the National Youth Administration, spoke along the same lines. He said:

We have no answers already written to the problems of young people. Those answers that we have are obviously meager and do not provide any general solution. ... I do not know that there are any answers we can write or put into effect.

To do very much about this situation may be beyond any group of people, no matter how sincere and how earnest they are. Certainly it reaches out and has implications for the whole growing concern of the Nation.

I quote these two leaders to indicate the humility with which the National Youth Administration approached this great problem. No one person and no small group knew the answer. The answer to the problem, and I think we have more than an inkling now as to what that answer really is, lay in the hearts of the tens of thousands of communities scattered throughout the United States.

Every individual connected with the now vast Youth Administration organization, from the President of the United States down to the individual youth beneficiary in the most remote sections of our country, is contributing to its solution. Whether we are on the right course, the reader will have to judge for himself.

Having close personal knowledge of the task attempted, I feel that this book accurately and vividly portrays the achievements of the National Youth Administration. I doubt if, in the annals of governments, there has ever been an official organization comparable in peacetime activity to NYA.

Enthusiasm, training, competency, humanity, and unceasing labor permeate the entire organization. Every field of social work is represented in its paid or volunteer personnel. Educators, social workers, religious leaders, labor leaders, farming experts, industrialists, doctors, nurses, all play their part. Not the least valuable contributors are the many leaders of private youth organizations, who have participated in our work actively or in an advisory capacity.

The entire Youth Administration, but particularly the National Advisory Committee, endeavors to work closely and sympathetically with various so-called youth movements and organizations of youth, irrespective of whether the ideas of these organizations are wholly approved of.

At a recent conference of the National Advisory Committee, the question of continuing to work with organizations of youth, some of which are popularly termed "radical," was discussed. The following significant statements were made by two members of the Advisory Committee and the thoughts therein contained were unanimously approved by the Committee:

I feel definitely that, if we hold ourselves aloof, we are stultifying and sacrificing our own opportunity to be helpful. And certainly what we did yesterday in having representatives of youth organizations join in with us in our discussions was just exactly the sort of thing we ought to do.

For if we are really in contact with these people, we will accomplish a great deal more than if we set ourselves up on heights and refuse to listen to any idea or contribution they have. I think our experience has been that if we let them see we are receptive and sympathetic, we will find they are in turn responsive, and then, when we have suggestions to make, we will find them a great deal more receptive sometimes to checks or brakes that we might wish to put on their activities than they would be if we set ourselves apart.[Note 1]

I am interested in youth unemployed, whatever the formula by which they express themselves. When we have an acute unemployment situation, we cannot expect that every movement will express itself in reasonable and sane terms.

We probably need to listen to them all the more because they are rather emotional and rather unusual in their terminology. But wherever they have actual elemental facts to point to, that points to our need to deal with those facts. In the second place, it is clear to me that we may overestimate the significance of the radical formulae used by youth today.

When they get emotionally interested, they are naturally going to seek out the most favorable form for protest they can find. Youth rejoices in being able to state a thing in a manner rather painful to his adults and it does not indicate at all that he is a revolutionary person getting ready to put a bomb under the American government.

I think we would make a very great mistake to keep out of touch with these matters. Thirdly, in proportion as we deal effectively with these people, even their use of the formulæ will tend to disappear. You cannot sustain formulæ on just language and if we can take the sting out of an unbearable situation, then radical formulæ are gone.[Note 2]

It is this broad, tolerant, democratic approach to the problems of youth which I believe has made so effective the methods used by the National Youth Administration.

I think there are five outstanding accomplishments that might be credited to the National Youth Administration, which are dramatically related in this book:

- That the Youth Administration has made an excellent start toward filling the gap between leaving school and finding a job.

- That a new technique in education is in the process of being developed: that is, education through work. The inclusion of related studies to actual work on a project has been an outstanding success.

- The exceptionally large percentage of youth trained on National Youth Administration projects who, after three to six months' combined work and education, have been able to find employment in private enterprise.

- That there has been found much socially useful work within the various communities that unemployed youth can be given, which will enrich the community as well as the lives of the erstwhile unemployed youth.

- That an average of over $50,000,000 per year was spent by tire government on this work at an administrative overhead of less than 5 percent.

I cannot, in this short introduction, name the hundreds of individuals who have contributed so largely to the success of the National Youth Administration. Yet, I cannot fail to mention one outstanding personality who, though having no official connection with the NYA, is recognized by acclamation as its spiritual leader.

I refer to Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt. Mrs. Roosevelt happens to hold a great position, but this is merely a coincidence in her relation to the National Youth Administration. She is by training and practice a social worker and a teacher but, above all, a great humanitarian.

Months before the National Youth Administration was created, Mrs. Roosevelt spent considerable time meeting with a group of representative underprivileged youth in New York City. This group, numbering about thirty, represented a cross-section of urban young people.

On several occasions, I had the privilege of attending these conferences at her home in New York. They were very informal. She had a graceful way of making these youth forget that she was the wife of the President of the United States and regard her only as a puzzled friend looking for a means of alleviating their condition.

I doubt if the young people knew that many details of these conferences were related by Mrs. Roosevelt to the President. When the President decided to create the National Youth Administration, he was acting not merely on his own considerable knowledge of the problem, but partly on a factual representation of the plight of youth conveyed directly to him by youth themselves through a sympathetic and wise messenger.

Since the formation of the NYA, Mrs. Roosevelt has kept in close and active touch with its work I question whether any individual has visited as many projects scattered throughout the entire United States as has Mrs. Roosevelt. Her wise criticism has on many occasions saved the National Youth Administration from making mistakes. Some of the projects enumerated or discussed here were conceived by her.

It is, therefore, fitting that this book should be dedicated to Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, not as First Lady, but as a woman of vision, intuition, and great love.

Charles W. Taussig.

End Notes

Betty and Ernest K. Lindley, "Introduction, etc.," in A New Deal for Youth: The Story of the National Youth Administration, New York: The Viking Press, 1938.

📖 Key Highlights & Findings from the Report

📌 The Urgent Need for the NYA

The report makes it clear that by the 1930s, the American youth faced an economic crisis of unprecedented scale. Taussig and other contributors outline four major national deficiencies that led to the creation of the NYA:

1️⃣ A Severe Lack of Jobs – Unemployment rates for young people were skyrocketing, with millions of high school and college graduates unable to find work.

2️⃣ An Inadequate Education System – Many states lacked sufficient public schools and vocational training programs, leaving millions of young Americans unprepared for employment.

3️⃣ Economic Inequality in Education – Vast portions of rural America had no access to schools or job training programs, and millions of youth were too poor to attend school, even when it was available.

4️⃣ The "Gap Years" Between School & Employment – Many young people were left adrift after finishing school, falling into poverty, crime, and radical political movements due to the lack of social support.

The NYA was designed to directly address these problems, providing work-study programs, vocational training, and financial aid to help young Americans become productive members of society.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images

📷 National Youth Administration Advertisement, c. 1939 – A promotional poster from Warren High School in Massachusetts, advertising debate and dance programs sponsored by the NYA. This highlights how the NYA wasn’t just about jobs—it also aimed to cultivate social and civic engagement among young people.

📜 Key Themes & Contributions of the NYA

🏛️ Strengthening Democracy Through Youth Employment

Taussig makes a strong argument that without meaningful jobs, education, and civic engagement, youth could become disillusioned with democracy. He warns that:

🔹 Economic instability makes youth vulnerable to extremist political ideologies.

🔹 A lack of opportunity creates resentment toward older generations.

🔹 Education and employment are key to preserving American democracy.

The NYA was seen as a safeguard against social unrest, helping young people build careers, contribute to their communities, and believe in the American system.

🎓 The NYA’s Impact on Education & Training

One of the NYA’s greatest accomplishments was its work-study programs, which allowed students to earn money while continuing their education.

✅ The NYA partnered with high schools, colleges, and trade schools to provide financial aid and vocational training.

✅ Thousands of young people gained technical skills in fields like mechanics, construction, nursing, and teaching.

✅ By combining education with hands-on work, the NYA pioneered a new model of experiential learning that still influences modern job training programs.

⚙️ Developing a Productive Workforce

The NYA wasn’t just about giving young people busy work—it was about creating a skilled workforce that could rebuild the nation.

🔹 Many NYA graduates found jobs in private industry after gaining skills through NYA projects.

🔹 Women were included in many NYA programs, an early step toward gender inclusion in the workforce.

🔹 The program addressed regional inequalities, bringing job training to rural and underdeveloped areas.

By investing in youth, the NYA helped revitalize entire communities while preparing a new generation for economic success.

📚 Relevance for Teachers, Students, Genealogists & Historians

📖 Why This Report Matters for Teachers & Students

✅ Offers a firsthand look at New Deal youth programs.

✅ Provides primary source material on education & labor policy.

✅ Sheds light on social and economic issues that remain relevant today.

📜 Why This Report is Valuable for Genealogists

✅ Contains records of youth employment & training programs, which may help researchers trace family members.

✅ Documents migration patterns as young people moved for job opportunities.

🏛️ Why Historians Should Study This Document

✅ Explores the intersection of economic policy, youth development & social reform.

✅ Reveals how government programs shaped America’s workforce.

✅ Highlights early steps toward gender and racial inclusion in job training.

⚖️ Discussion of Bias in the Content

📌 Potential Biases in the Report

The report is largely positive, focusing on NYA successes while downplaying failures or criticisms.

Racial & gender inequalities are not deeply addressed, even though many NYA programs excluded Black and female workers.

The government’s role in controlling education & employment is portrayed as entirely positive, without much discussion of potential downsides.

📌 Why This Bias Matters

Historians should read this document alongside other sources, including firsthand accounts from NYA participants and critical analyses of New Deal programs to get a balanced perspective.

🏗️ Final Thoughts: Why This Document Matters

The National Youth Administration played a critical role in shaping American labor policy, workforce training, and youth education. This 1938 report provides an invaluable look at how the U.S. government tackled youth unemployment, offering important lessons for today’s educators, policymakers, and historians.

📌 Ultimately, this document is a testament to how investing in youth can transform a nation’s future. 🌎✨