📖 Breaking the Cycle: How the NYA Gave Hope to Depression-Era Youth

📜 Explore how the National Youth Administration (NYA) helped millions of unemployed youth during the Great Depression by providing jobs, education, and job training. A must-read for educators, historians, and genealogists.

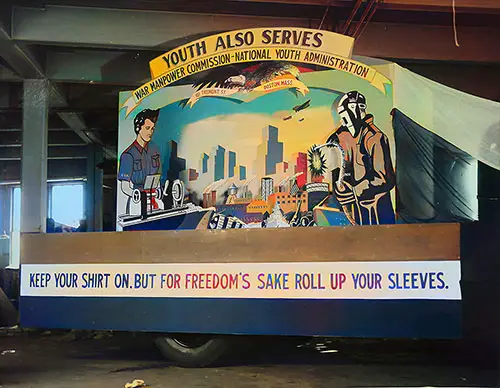

The Photograph Titled “War Manpower Commission and National Youth Administration Float, c. 1941” Shows a Float Used to Promote the War Manpower Commission and the National Youth Administration’s Training Programs for Youth Aged 16 to 24 During World War II. These Programs Focused on War Production Training. National Archives and Records Administration, NAID: 7351386. Colorized by GG Archives for Emphasis. GGA Image ID # 2228faf8d4

📜 Out of School and Out of Work – NYA Youths (1938)

📖 "Breaking the Cycle: How the NYA Gave Hope to Depression-Era Youth"

The Great Depression left millions of young Americans without education, employment, or opportunity—a crisis that could have resulted in a "lost generation." The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a crucial intervention, providing part-time jobs, job training, and financial assistance to youth aged 16-24.

"Out of School and Out of Work" paints a gripping portrait of these young people, many of whom came from large families struggling on public relief. It explores the severe economic struggles that forced students to drop out of school, their bleak employment prospects, and how NYA work projects restored their dignity, financial independence, and hope.

This document is especially valuable for:

✅ Teachers & Students studying New Deal policies, labor history, and social welfare programs.

✅ Historians analyzing youth unemployment and job training programs during the 1930s.

✅ Genealogists researching family members who participated in NYA work projects.

✅ Sociologists & Economists examining the effects of long-term unemployment on young workers.

"Where have you worked before?"

"How long did you go to school?"

These are the two eternal questions asked the young man or woman looking for a job. One 18-year-old boy with whom we talked summed up his own experiences by saying:

"I had to quit school when I was in the eighth grade because my old man didn't have a job and he said I'd have to get out and do something. I've been trying to do something ever since. . . . Once in a while I get some handbills to throw out. When there's a chance for a job, and that don't come but once in a blue moon, what do they ask you? 'Where did you work last?' If you haven't had a job, they don't even want to talk to you. But where you gonna get that first job? I ask you. It takes carfare to go around looking, too, and that don't grow on apple trees."

The work program of the NYA, started in January 1936, has been developed to meet the needs of the lowest-income group of boys and girls who have grown up in the depression. In April 1938, 180,000 unmarried young people from 18 to 24 years old were employed part-time on a wide variety of NYA work projects.

Who Are the NYA Project Workers?

Ninety-five percent, of them come from families certified as in need of public relief. Most of these families are unusually large; more than one-third of them have seven or more to feed, clothe, and shelter; 29 percent, more are families numbering five and six to a household; 28 percent, are families of four. Only 9 percent, are families of three (with one child). [Note 1]

It is not hard to imagine the difficult home situations these young people face. Their parents have fully expected that they would be self-supporting by the time they were 18, if not sooner; undoubtedly many have anticipated that their sons, at least, would contribute something to the family income.

Instead, the jobless young people have been a further drain on already incredibly meager family incomes. Although the NYA work program may employ unmarried youth 18 to 24 years old, the average age of project workers today is slightly under 20. [Note 2]

They are divided almost equally between the sexes. Racially, their distribution among whites, Negroes, Indians, and other racial minorities is in proportion to the general population.

Perhaps the most arresting data about this large cross-section of underprivileged youth are on their educational background. The United States spends more than any other nation in the world on its educational system, but a study of 35,638 youth on NYA work projects [Note 3] reveals that we have a considerable group who have not had a fair share in this education. Only half of these NYA boys and girls ever went to school a day beyond the eighth grade.

About 47 percent, of them left school between the ninth and twelfth grades, and only about 3 percent, attended college at all. This study included no States in the deep South, where the educational level is still lower.

In Louisiana, the school attendance of white boys and girls on the NYA work program averages six years; of Negro youth, one year more. [Note 4] In Colorado, youth on the NYA work program have spent an average of only six years in school.

Arkansas relief youth, on the average, left their schoolbooks behind them between the sixth and seventh grades—and the majority of rural schools in Arkansas are open only six months a year. On one work project that we visited in the mountains of Kentucky, 17 of the 26 boys could neither read nor write when they became NYA workers, and we were told that they were typical of the relief youth in that area.

In an attempt to discover why so many of these young people left school at such an early age, a sample questionnaire was sent to 13,547 of them. [Note 5] Financial difficulties accounted for about 47 percent; discouragement and lack of interest were the reasons given by 25 percent.

If these young people have not been in school, what have they been doing? We asked a number of them this very question. "I lie around and look for work," and "Oh, I don't know, what is there to do?" are typical answers.

A study of almost 20,000 project youth [Note 6] shows that before NYA employment one-third had never had any kind of job at all; one-sixth had done some work as unskilled laborers; one-eighth reported some employment as domestics; one-tenth had at some time found a little work as farm hands; another tenth had been employed in factories or workshops.

The remaining 17.5 percent had held odd jobs in a variety of fields. Without question, the great majority of NYA youth who reported some work experience have had only temporary jobs. For example, the one-tenth who had been farm hands had gone into the harvest fields for a few weeks a year.

Many of those in domestic work had done odd jobs around a household or cared for children for a few hours a week. Christmas and other seasonal or sporadic employment probably accounts for large numbers more. It seems conservative to conclude that the great majority of youth now working on NYA projects have never had regular jobs.

What Does NYA Offer Them?

The work program gives this group of young people an average of 44.5 hours' work a month with an average monthly pay of $15.73. [Note 7]

We can gather the meaning of these hours of work and these dollars of pay only by the observations we have made and the comments we have heard as we have traveled over the country, seeing projects and youth and talking with supervisors and members of communities who have watched the development of the NYA work program.

We have seen and heard abundant indications that the great majority of young people on relief are eager to work. For years, to most of them, a job has been a fabulous unreality. Here is at least part-time work on which they can depend. Someone wants their efforts.

In every State in which we asked: "What do NYA workers do with their money?" we got the same answers. First, they help at home; overnight, they have placed themselves on the asset side of the family ledger; instead of being another person to share limited family food supplies, each can contribute something to the family expenses.

The value of this shedding of the feeling of guilt and defeat, which this contribution to the family means, cannot be computed. This is one boy's description of what his NYA job has meant to him:

"Maybe you don't know what it's like to come home and have everyone looking at you, and you know they're thinking, even if they don't say it, 'He didn't find a job.' It gets terrible. You just don't want to come home. . . . But a guy's gotta eat some place and you gotta sleep some place. ... I tell you, the first time I walked in the front door with my paycheck, I was somebody!"

After they have helped out at home, we were told, most of these young workers buy themselves some clothes; for years they have worn hand-me-downs.

"Usually, after about the second pay-check," a NYA supervisor said, "a boy will come to work with a new pair of trousers. They probably cost him two or three dollars, but they're his and he bought them with his own money. Maybe on his next wages he'll get a pair of shoes.

The girl will blossom out in a $2.95 dress. You can't possibly know what it means to her. We notice that she keeps herself cleaner, that her hair isn't straggling all over the place. You can actually see shoulders straightened up when these boys and girls appear with their new clothes."

If they have any money left, there is a little chance for entertainment—a movie, taking a girl for an ice cream soda, going to a dance, riding in a bus. One boy with whom we talked must be typical of many.

"It makes you feel like a man to have some money jingling in your pocket," he said.

The Evolution of NYA Work Projects

When funds amounting to $30,000,000 a year were first made available for youth work projects in the fall of 1935, the newly formed National Youth Administration in Washington was firm in its stand for a decentralized program.

The specific needs of youth in New York City, for example, were totally different in character from the wants of the Kentucky mountaineers or of the Arkansas sharecroppers. A Youth Director for each State was appointed, and he, in turn, divided his State into districts, with supervisory personnel for each.

State organizations began to plan a host of projects. Boys and girls were to be put to work in January 1936. This general picture of these first days of NYA by one State director is typical of what we heard also from several others:

"We were told we had so much money allotted to us, and that we could put as many relief boys and girls to work as possible with that money, within the general regulations about wages and hours of work. When we asked Washington: "What kind of work?' we were told: 'That's up to you. Plan the best projects you can. Get them sponsored by public agencies in your own communities. Go to it.' We did.

But we didn't know, we couldn't possibly have known, what kind of work these youth wanted and needed. We planned it the best we could. We wanted good sponsors who would provide us with places for work projects, money for materials, and help with supervision.

They were hard to get then, because many of them thought these young people were only loafers. Well, it seemed at that time that the quickest way to get our boys and girls to work was to put them in obvious jobs, like helping to supervise young children on public playgrounds.

It didn't take us very long to find out that work like that was for only a very few of our youth. The rest were wasting time. Then we got clerical jobs for a lot of them—too many of them—in city and county and State offices. Only a certain number belonged there.

We realized that we had to have other kinds of work, many other lands. We formed State and local advisory committees of men and women with fundamental interests in youth and we asked them to help us to plan honest and real work.

We talked with the youth and they had good ideas. We found out that we needed a great variety of work, because young people don't fit into any one or two—or six—grooves."

End Notes

Note 1: From a sample research of 19,306 youth on NYA work projects in California, Kentucky, Nebraska, Ohio, and New York City.

Note 2: From a sampling of 6697 project youth in California, Nebraska, and Ohio. Also Youth Directors in nine States other than the above three report average age of project youth as between 19 and 20.

Note 3: From a sample research of 35,638 project youth in Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, California, Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, New Hampshire, and New York City.

Note 4: We inquired into the reasons for the slightly longer school attendance of Negro youth in this group. Most frequently we were told that in these families of very low income, many Negro women seek and obtain some work as domestic servants, whereas white women rarely do, with the result that Negro children sometimes can remain in school a little longer. However, it should be noted that, owing to the generally lower standards in Negro schools, the education of Negroes who have been in school seven years may be poorer than that of white children who have been in school only six years.

Note 5: From a sampling of 15,547 youth on work projects in California, Kentucky, Minnesota, and Ohio.

Note 6: In California, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and West Virginia. Youth directors in most of the States we have visited, other than these six, estimate a much higher percentage of youth with no work experience whatsoever. The lowest estimate we have had from these directors is 50 percent, and the highest is 95 percent.

Note 7: Official WPA regulations state that the maximum hours of work for NYA project youth shall be 8 hours a day, 40 hours a week, and 70 hours a month. Earnings range from a minimum of $10 to a maximum of $25 a month, based on wage rates established in accordance with prevailing local wage standards. Administrative Order No. 60 of the Works Progress Administration.

Betty and Ernest K. Lindley, "Out of School and Out of Work," in A New Deal for Youth: The Story of the National Youth Administration, New York: The Viking Press, 1938, pp. 17-23.

📌 Key Highlights & Findings

📊 The Harsh Reality of Depression-Era Youth

📌 180,000 young people were employed by the NYA in 1938.

📌 95% of NYA project workers came from families on public relief.

📌 One-third of NYA youth had never held a job before enrolling in the program.

📌 More than half left school before the ninth grade, many forced out due to family financial struggles.

📌 Why did youth drop out of school?

- 47% cited financial struggles (families couldn’t afford for them to stay in school).

- 25% felt discouraged or lost interest due to economic instability.

Many lacked basic education, especially in the South, where schools were open only six months per year.

📌 What were they doing before NYA?

Many were idle, unable to find work or training.

Some took on odd jobs (farm work, domestic labor, seasonal employment).

Others wandered from place to place searching for any job opportunity.

🛑 The biggest problem? Employers refused to hire youth without experience—but youth couldn’t get experience without a job. The NYA broke this cycle by providing work opportunities.

🛠️ What Did NYA Offer?

📜 A Lifeline for Jobless Youth

🔹 The NYA provided part-time jobs (average 44.5 hours per month) with monthly earnings of $15.73.

🔹 Work projects were designed to be meaningful, offering training in public service, construction, education, and clerical work.

🔹 NYA work gave youth stability—for many, it was their first real job experience.

📌 Where did the money go?

✅ Helping their families—for the first time, they contributed to household expenses.

✅ Buying clothes—many had worn hand-me-downs for years.

✅ Entertainment & social life—for some, NYA wages meant they could afford a movie ticket, a dance, or an ice cream soda for the first time.

💬 Testimonial from an NYA Worker:

🗣️ "Maybe you don’t know what it’s like to come home and have everyone looking at you, and you know they’re thinking, even if they don’t say it, ‘He didn’t find a job.’ It gets terrible. You just don’t want to come home... But a guy’s gotta eat some place. I tell you, the first time I walked in the front door with my paycheck, I was somebody!"

✅ NYA provided more than just jobs—it restored pride and self-worth.

🚀 Evolution of NYA Work Projects

🏗️ Adapting to the Needs of Youth

🔹 When NYA first started in January 1936, its projects were experimental, focusing on:

- Playground supervision

- Clerical work in government offices

- Other community-based jobs

🔹 However, these early projects did not meet the diverse needs of unemployed youth.

🔹 By 1938, NYA projects had expanded significantly, offering:

- Industrial training (factory work, auto repair, metalwork)

- Education-based work (literacy programs, school tutoring)

- Public service jobs (community construction, park maintenance)

🔹 Local control was key—NYA allowed states and cities to shape projects based on local economic needs.

💡 Lesson for today? The NYA was flexible and responsive—a model for modern youth employment programs.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images & Their Significance

📷 "War Manpower Commission and National Youth Administration Float, c. 1941"

👉 Shows a float promoting NYA's training programs during WWII.

✅ Significance: Demonstrates how NYA adapted to wartime needs, shifting its focus to war production training.

🌎 Why This Document Matters for Educators, Historians & Genealogists

📖 For Teachers & Students

✅ Explains how government programs helped unemployed youth during the Great Depression.

✅ Provides a real-world example of "learning through work".

✅ Encourages discussion on modern youth employment issues.

📜 For Genealogists

✅ NYA work records can help trace family members who may have been participants.

✅ Provides historical context for the economic struggles of young adults in the 1930s.

🏛️ For Historians

✅ Examines the role of government intervention in economic crises.

✅ Explores youth unemployment as a social issue beyond just the Great Depression.

✅ Highlights how economic struggles influenced education and job training policy.

⚖️ Discussion of Bias in the Content

📌 Potential Biases in the Report

🔹 The document praises the NYA extensively, with little criticism of inefficiencies or failures.

🔹 Race & gender disparities are only briefly mentioned—a more nuanced analysis of the challenges faced by minority and female participants is missing.

🔹 There’s no discussion of opposition to the program from business leaders or politicians who believed government job programs hurt private enterprise.

📌 Why This Bias Matters

To fully understand the NYA’s impact, researchers should cross-reference this document with other sources, such as:

🔹 Congressional debates on NYA funding & effectiveness.

🔹 Testimonies from business owners & private employers.

🔹 Oral histories from NYA participants.

🏗️ Final Thoughts: The NYA’s Lasting Legacy

The National Youth Administration was a transformative New Deal program, ensuring that millions of young Americans were not permanently left behind by the Great Depression.

📌 This report highlights the NYA’s critical role in shaping the future workforce, reinforcing the importance of government intervention during economic crises. 🌎✨