The Birth of Café Culture: Parisian Coffeehouses from 1650 to the Revolution

📌 Discover the fascinating history of Parisian coffeehouses, from their humble origins in the 17th century to their role in shaping literature, politics, and intellectual life. Explore the stories of Café de Procope, Voltaire, and the first street coffee vendors. A must-read for coffee lovers, historians, and epicureans! ☕✨

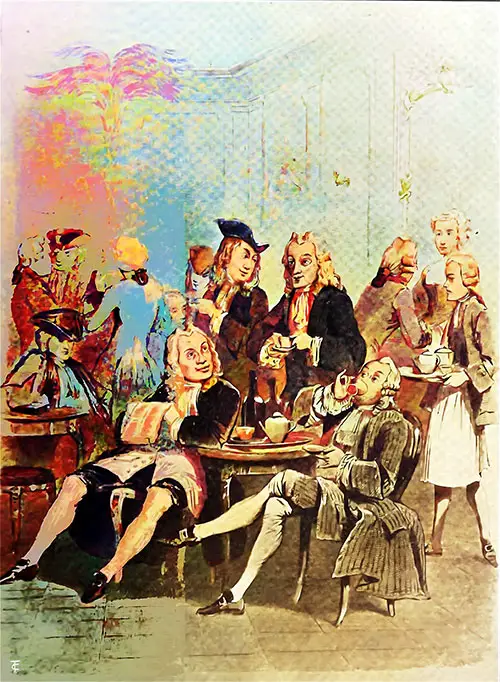

Scene From an Early Parisian Café, Featuring Two Men and a Woman Engaged in Discussion While Enjoying Their Coffee. Sketch by Tufant. Old and New Paris, 1893. GGA Image ID # 222ae8e98d

☕ The Birthplace of Café Culture: A Deep Dive into Early Parisian Coffee Houses

🔎 Why This Article Matters for Epicureans, Food Historians, Teachers, and Coffee Lovers

Few things embody French culture and refinement more than the Parisian café, and this 1922 article on the history of early Parisian coffee houses offers a fascinating deep dive into their origins, influence, and evolution. From humble beginnings in 1657 to their transformation into literary salons, revolutionary meeting spaces, and artistic hubs, this piece captures the romance and cultural significance of the café experience.

✅ Epicureans & coffee lovers – A historical journey into how cafés became central to Parisian life and socialization.

✅ Food historians & educators – Insight into how coffee influenced French culture, literature, politics, and gastronomy.

✅ Students & researchers – A rich historical account that connects the past to modern café traditions.

Paris is celebrated above all the capitals of Europe for its cafes, and the beverage that gives its name to these establishments has been known earlier in France than in any other European country.

Coffee was introduced into central Europe in 1683, the year of the battle of Vienna, and from the Austrian capital, its use spread rapidly to all parts of Germany.

Parisians, however, pride themselves on having known coffee fourteen years earlier than the Viennese. Indeed, an enterprising Levantine started a coffee house in Paris in the very middle of the seventeenth century, not later than 1650.

The name of the stimulating beverage that he offered for sale was, as he wrote it, "cahoue." But the unhappy man had not taken the necessary steps to get his new importation spoken of beforehand in good society. No one knew what to make of the strange liquor he wished to dispense—hot, black, and bitter— the founder of the first coffee house or café became bankrupt.

Drawing of A group of people is gathered outside Théâtre des Variétés, at a nearby a cafe. The view focuses on a Cafe on the Boulevard Montmartre near the entrance of Théâtre des Variétés. Old and New Paris, 1893. GGA Image ID # 222af4e940

The introduction of coffee into Paris by Thévenot in 1657 — How Soliman Aga established the custom of coffee drinking at the court of Louis XIV — Opening the first coffee houses — The French adaptation of the Oriental coffee house, which first appeared in the authentic French cafe of François Procope, a significant figure in this cultural exchange — The important part played by the coffee houses in the development of French literature and the stage — Their association with the Revolution and the founding of the Republic — Quaint customs and patrons — Historic Parisian cafes.

Before the year 1669, coffee was a rare sight in Paris, with only a few glimpses at M. Thévenot's and the homes of his friends. Its existence was mostly confined to the pages of travelogues, as Jean La Roque's authority suggests.

As noted in his book, Jean de Thévenot brought coffee into Paris in 1657. One account says that a decoction, supposed to have been coffee, was sold by a Levantine in the Petit Chatelet under the name of "cohove" or "cahoue" during the reign of Louis XIII; but this lacks confirmation. Louis XIV is said to have been served with coffee for the first time in 1664.

Following the arrival of the Turkish ambassador, Soliman Aga, in July 1669, the popularity of coffee in Paris skyrocketed. His lavish coffee functions and generous servings of the beverage at the court and in the city led to the widespread adoption of the drink.

Within six months, Paris was talking about the sumptuous coffee functions of the ambassador from Mohammed IV to the court of Louis XIV.

Despite the slow start with Louis XIV's court, coffee found a fervent supporter in the next king, Louis XV. His desire to please his mistress, Mme. du Barry, led to a coffee craze, with the king reportedly spending a hefty $15,000 a year on coffee for his daughters.

This Sketch Depicts When Coffee Was First Sold and Served Publicly in the Fair of St. Germain. The Fair of St. Germain, Held Annually Between February and Easter Sunday, Was One of Paris’s Oldest and Most Popular Fairs. It Was Housed in Semi-Permanent Buildings and Sold Textiles, Paintings, and Other Fashionable and Luxury Goods. However, the Fair Was More Than Just a Marketplace. It Was Pivotal in Developing the Commedia Dell’arte, a Significant Cultural Contribution. All About Coffee, 1922. GGA Image ID # 222b285ed0

Meanwhile, in 1672, one Pascal, an Armenian, first sold coffee publicly in Paris. Pascal, who, according to one account, was brought to Paris by the Turkish ambassador, Soliman Aga, offered the beverage for sale from a tent, which was also a kind of booth, in the fair of St. Germain, supplemented by the service of Turkish waiter boys, who peddled it among the crowds from small cups on trays.

The fair was held during the first two months of spring in a large open plot just inside the walls of Paris and near the Latin Quarter. As Pascal's waiter boys circulated through the crowds on those chilly days, the fragrant odor of freshly made coffee brought many ready sales of the steaming beverage. Soon, visitors to the fair learned to look for the 'little black' cupful of cheer, or 'petit noir,' a name that still endures.

When the fair closed, Pascal opened a small coffee shop on the Quai de l'Ecole near the Pont Neuf. However, his frequenters were of the type who preferred the beers and wines of the day, and coffee languished.

Pascal continued to send his waiter boys, with their large coffee jugs, which were heated by lamps, through the streets of Paris and from door to door. Their cheery cry of "café! café!" became a welcome call to many a Parisian, who later missed his petit noir when Pascal gave up and moved on to London, where coffee drinking was then in high favor.

Street Coffee Vendor of Paris — Period. 1672 to 1689 Two Sous per Dish, Sugar Included. All About Coffee, 1922. GGA Image ID # 222b2867cc

Lacking favor at court, coffee's progress was slow. The French fashionable set clung to its light wines and beers. In 1672, Maliban, another Armenian, opened a coffee house in the rue Bussy, next to the Metz tennis court near St.-Germain's abbey. He also supplied tobacco to his customers.

All these, and others, were essentially the Oriental style of coffee houses of the lower classes, and they appealed principally to the poorer classes and foreigners. "Gentlemen and people of fashion" did not care to be seen in this public house. But when the French merchants began to set up, first at St.-Germain's fair, "spacious apartments in an elegant manner, ornamented with tapestries, large mirrors, pictures, marble tables, branches for candles, magnificent lusters, and serving coffee, tea, chocolate, and other refreshments," they were soon crowded with people of fashion and men of letters.

In this way, coffee drinking in public acquired a badge of respectability. Presently, there are some three hundred coffee houses in Paris. In addition to plying their trade in the city, the principal coffee men maintained coffee rooms in St. Germain's and St. Laurence's fairs. Women, as well as men, frequented these.

A Sketch of a Scene at the Cafe de Procope in 1743 Depicts Several Patrons Enjoying Their Coffee. The Café Procope, Also Known As Le Procope, on the Rue de L’ancienne Comédie, Is a Café in the 6th Arrondissement of Paris. the Original Café, Opened in 1686 by the Sicilian Chef Procopio Cutò, Became the Hub of the Parisian Artistic and Literary Community in the 18th and 19th Centuries. It Is Sometimes Erroneously Called the Oldest Café in Continuous Operation; However, the Original Café Closed in 1872, and the Space Was Used in Various Ways Before 1957, When the Current Incarnation Opened. All About Coffee, 1922. Colorized by GG Archives for Effect. GGA Image ID # 222b512eb3

The Progenitor of the Real Parisian Café

It was not until 1689 that an actual French adaptation of the Oriental coffee house appeared in Paris. This was the Café de Procope, opened by Francois Procope (Procopio Cultelli, or Cotelli), who came from Florence or Palermo. Procope was a lemonade (lemonade vendor) with a royal license to sell spices, ice, barley water, lemonade, and other refreshments. He early added coffee to the list and attracted a large and distinguished patronage.

Procope, a keen-witted merchant, made his appeal to a higher class of patrons than did Pascal and those who first followed him. He established his café directly opposite the newly opened Comédie Française, in the street then known as the rue des Fosses-St.-Germain, but now the rue de l'Ancienne Comédie.

Because of its location, the Café de Procope became the gathering place of many noted French actors, authors, dramatists, and musicians of the eighteenth century. It was a veritable literary salon. Voltaire was a constant patron, and until the café closed after more than two centuries, his marble table and chair were among the precious relics of the coffee house. His favorite drink is said to have been a mixture of coffee and chocolate.

Naturally, the name of Benjamin Franklin, recognized in Europe as one of the world's foremost thinkers during the American Revolution, was often spoken over the coffee cups of Café de Procope. When the distinguished American died in 1790, this French coffee house went into deep mourning "for the great friend of "republicanism." The walls, inside and out, were swathed in black bunting, and all frequenters acclaimed Franklin's statesmanship and scientific attainments.

The Café de Procope looms large in the annals of the French Revolution. During the turbulent days of 1789, people could be found at the tables drinking coffee or stronger beverages and engaged in debate over the burning questions of the hour.

After the Revolution, the Café de Procope lost its literary prestige and sank to the level of an ordinary restaurant. History records that coffee became firmly established in Paris with the opening of the Café de Procope. During Louis XV's reign, 600 cafés were built in Paris. At the close of the eighteenth century, there were more than 800. By 1843, the number had increased to more than 3000.

Café de foy, Known As the Patriots’ cafe, In the palais-Royal, Paris, 1789. Sketch Shows a Distinguished Gentleman Talking to Two Ladies Sitting at the Café. All About Coffee, 1922. GGA Image ID # 222b5a2fec

The Development of the Cafés

Coffee's vogue spread rapidly, and many cabarets and famous eating houses began to add it to their menus. Among these was the Tour d'Argent (silver tower), which had opened on the Quai de la Tournelle in 1582 and speedily became Paris's most fashionable restaurant.

It is still one of the chief attractions of the epicure, retaining its reputation for its cooking, which drew a host of world leaders, from Napoleon to Edward VII, and its quaint interior.

When coffee houses began growing rapidly in Paris, the majority centered in the Palais Royal, "that garden spot of beauty, enclosed on three sides by three tiers of galleries." Soon after the opening of the Café de Procope, it began to blossom with many attractive coffee stalls or rooms sprinkled among the other shops that occupied the galleries overlooking the gardens.

The beginnings of the Regency coffee house are associated with the legend that Lefevre, a Parisian, began peddling coffee in the streets of Paris when Procope opened his café in 1689.

The story has it that Lefevre later opened a café near the Palais Royal, selling it in 1718 to one Leclerc. Leclerc named it the Café de la Régence in honor of the regent of Orleans, a name that still endures on a broad sign over its doors. After paying their court to the regent, the nobility had their rendezvous there.

Parisians Enjoying a Beautiful Day at a Café on the Boulevard Montmartre, Paris, 1893. Old and New Paris, 1893. GGA Image ID # 222c349735

To name the patrons of the Café de la Régence in its long career would be to

outline the history of French literature for more than two centuries. There was Philidor the "greatest theoretician of the eighteenth century, better known for his chess than his music"; Robespierre, of the Revolution, who once played chess with a girl disguised as a boy for the life of her lover; Napoleon, who was then noted more for his chess than his empire-building propensities; and Gambetta, whose loud voice, generally raised in debate, disturbed one chess player so much that he protested because he could not follow his game.

Chess is still in favor of the Régence. However, as

were the earlier patrons, the players are not obliged to pay by the hour for their tables with extra charges for candles placed by the chess boards. The present Café de la Régence is in the rue St. Honoré. Still, it retains its aspect of golden days in considerable measure.

The vogue of coffee popularized sugar, which was then bought by the ounce at the apothecary's shop. Dufour says that in Paris, they used to put so much sugar in the coffee that "it was nothing but a syrup of blackened water." The ladies were wont to have their carriages stop in front of the Paris cafés and to have their coffee served to them by the porter on silver saucers.

New cafés open every year. As they became numerous and competitive, it became necessary to invent new attractions for customers.

Then was born the café chantant, where songs, monologues, dances, little plays, and farces (not always in the best taste) were provided to amuse the frequenters. Many of these cafés chantants were in the open air along the Champs-Elysees.

In bad weather, Paris provided the pleasure-seeker with the Eldorado, Alcazar d'Hiver, Scala, Gaiete, Concert du XIXme Steele, Folies Bobino, Rambuteau, Concert European, and countless other meeting places where one could be served with a cup of coffee.

As in London, certain cafés were noted for particular followings, like the military, students, artists, and merchants. The politicians had their favorite resorts.

.

The Cafe Des Mille Colonnes in 1811. Café Des Mille Colonnes Was Located on the First Floor, in The montpensier Gallery, Near The café de Foy. All About Coffee, 1922. GGA Image ID # 222ca7d305

Historic Parisian Cafés

Some historic cafés are still thriving in their original locations, although the majority have now passed into oblivion. Glimpses of the more famous houses are found in the novels, poetry, and essays written by the French literati who patronized them.

These first-hand accounts give insights that are sometimes stirring, often amusing, and frequently revolting — such as the assassination of St. Fargeau in Fevrier's low-vaulted cellar café in the Palais Royal.

Perhaps the Boulevard des Italiens had, and still has, more fashionable cafés than any other section of the French capital. The Tortoni, opened in the early days of the Empire by Velloni, an Italian lemonade vendor, was the most popular of the boulevard cafés and was generally thronged with fashionables from all parts of Europe.

Here, Louis Blanc, historian of the Revolution, spent many hours in the early days of his fame... Farther down the boulevard were the Café Riche, Maison Poree, Café Anglais, and the Café de Paris.

The Riche and the Doree, standing side by side, were both high-priced and noted for their revelries. The Anglais, which came into existence after the snuffing out of the Empire, were also distinguished for their high prices but, in return, gave an excellent dinner and fine wines. It is told that even during the siege of Paris, the Anglais offered its patrons "such luxuries as ass, mule, peas, fried potatoes, and champagne."

La Belle Limonaudière at Café Des Mille Colonnes, Palais Royal, Paris, 1814. This Hand-Colored Etching Depicts Patrons at the Famous Parisian Café Enjoying Their Coffee, Caricature Created by British Artist Thomas Rowlandson. La Belle Limonadière Was Also a Parisian Personality Known for Her Striking Beauty During the First Empire and the Early Years of the Restoration. Image Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Rosenwald Collection, 1945-5-1254-b. GGA Image ID # 222c3da111

The Café de Paris, which opened in 1822 in the former home of the Russian Prince Demidoff, was the most richly equipped and elegantly conducted café in Paris in the nineteenth century.

The Café Literaire opened on Boulevard Bonne Nouvelle late in the nineteenth century, made a direct appeal to literary men for patronage, printing this footnote on its menu: "Every customer spending a franc in this establishment is entitled to one volume of any work to be selected from our vast collection."

An Everyday Scene at Café de La Paix by Georges Croegaert, 1883. Croegaert Was a Belgian Artist (1848–1923). GGA Image ID # 222cb10590

The Grand Café de Paris, Place du Théâtre in 1843. All About Coffee, 1922. GGA Image ID # 222cc1908d

Interior of a Typical Parisian Cafe of the Early Nineteenth Century. All About Coffee, 1922. GGA Image ID # 222ccb50d8

Chess has been a favorite pastime at the Café de la Régence. The Café de la Régence in Paris was an important European chess center in the 18th and 19th centuries. All important chess masters of the time played there. The Café's masters included but were not limited to, Paul Morphy. All About Coffee, 1922. GGA Image ID # 222ccfa050

Ukers, William H., M.A., All About Coffee, "Chapter XI: History of the Early Parisian Coffee Houses," New York: The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company, 1922, p. 91-104.

🔥 Key Takeaways: What Makes This Article a Café Lover’s Dream?

☕ The Dawn of Coffee Culture in Paris

🔹 While coffee arrived in Vienna in 1683, Parisians had already been sipping the dark elixir as early as 1650.

🔹 The first known coffee house in Paris was an absolute failure—an Armenian merchant tried selling "cahoue," but without proper marketing, the black, bitter drink was met with suspicion.

🔹 It wasn’t until 1672 that Pascal, another Armenian, successfully introduced coffee at the Fair of St. Germain, where its warm aroma and exotic flavor won over Parisians.

💡 Why It’s Interesting:

✅ For foodies & coffee lovers – A rare glimpse into coffee’s rocky start in Europe.

✅ For historians – A cultural case study in how foreign imports became deeply French.

👑 Louis XIV, the Turkish Ambassador, and the Spread of Coffee

🔹 The Turkish ambassador Soliman Aga revolutionized coffee culture in Paris in 1669, hosting lavish coffee ceremonies at Versailles.

🔹 Despite initial resistance at the royal court, Louis XV eventually fell in love with coffee, spending $15,000 a year on the beverage.

💡 Why It’s Interesting:

✅ For students & teachers – A historical connection between diplomacy, trade, and culinary evolution.

✅ For coffee lovers – An early example of coffee as a luxury and status symbol.

🏛️ The First True Parisian Café: Café de Procope (1686)

🔹 François Procope opened the Café de Procope, the first true Parisian café, directly across from the Comédie Française.

🔹 It became the meeting place for some of the greatest minds in history, including Voltaire, Rousseau, and later Benjamin Franklin.

🔹 It played a major role in the French Revolution—Danton, Marat, and Robespierre all met here to discuss radical new ideas.

💡 Why It’s Interesting:

✅ For literature & history lovers – A café where Enlightenment and revolutionary ideas took shape.

✅ For educators & students – A perfect example of how coffeehouses shaped politics and philosophy.

🎭 The Rise of Café Culture and the Birth of Parisian Intellectualism

🔹 By 1700, coffeehouses were the center of intellectual life, much like the Greek agora or Roman forums.

🔹 Café patrons were divided by profession and interest—students, artists, merchants, politicians, and aristocrats all had their own preferred spots.

🔹 By 1843, there were over 3,000 cafés in Paris, each with its own distinct clientele and atmosphere.

💡 Why It’s Interesting:

✅ For sociologists & historians – A fascinating look at how cafés became social institutions.

✅ For modern café lovers – The origins of today’s specialty coffee movement can be traced here.

🖼️ Noteworthy Images & Their Significance

📌 "Scene from an Early Parisian Café (1893)"

➤ A beautiful artistic sketch capturing the spirit of early coffeehouses, where people gathered to debate, read, and sip coffee.

📌 "Street Coffee Vendor of Paris (1672-1689)"

➤ Depicts the first portable coffee vendors, marking the beginning of "to-go" coffee culture in Paris.

📌 "Café de Procope in 1743"

➤ The legendary café where Voltaire, Rousseau, and Franklin gathered, an intellectual and revolutionary landmark.

📌 "La Belle Limonaudière at Café des Mille Colonnes, Palais Royal, 1814"

➤ A romanticized portrait of Parisian café culture, showcasing the elegance, fashion, and sophistication of 19th-century coffee drinking.

🎯 Final Thoughts: Why This Article Still Matters Today

Parisian coffeehouses weren’t just places to drink coffee—they were hubs of creativity, debate, and revolution. This 1922 article captures the magic of their origins and shows how they shaped French culture, literature, and history.

✅ For coffee lovers & café enthusiasts – This is the ultimate origin story of café culture.

✅ For food historians & educators – A detailed, well-researched look at the intersection of coffee, politics, and social change.

✅ For epicureans & travelers – An inspiring guide to Parisian café history, perfect for those who love coffee, history, and French culture.

💡 Whether you’re sipping an espresso at Café de Flore or reading this in a modern coffee shop, this article reminds us that every cup of coffee is a sip of history. ☕✨