Fruits of the Titanic Disaster - 1913

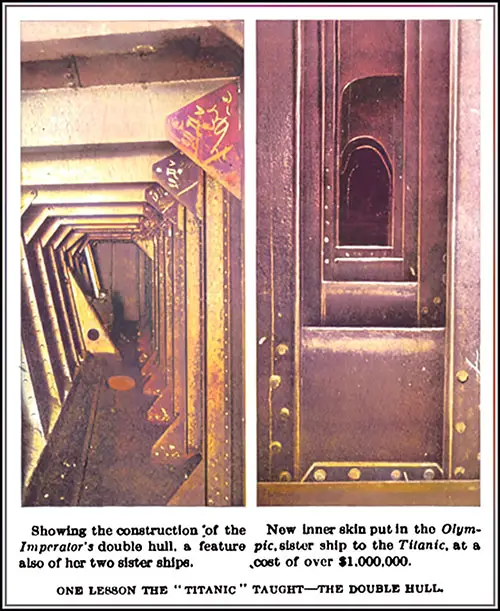

One Lesson The Titanic Taught -- The Double Hull. On the left is the construction of the Imperator's double hull, a feature of her two sister ships. On the right, designers put new inner skin in the RMS Olympic, the sister ship to the Titanic, at over $1,000,000. The Literary Digest (26 April 1913) p. 937. GGA Image ID # 1088bb8198

Introduction

The sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 14, 1912, was a watershed moment in maritime history, profoundly changing the way the world viewed ocean travel safety. One year after the disaster that claimed the lives of over 1,500 passengers and crew, the world began to see the fruits of the lessons learned from this tragedy. The article "Fruits of the Titanic Disaster - 1913" explores the various safety improvements, legislative reforms, and technological advancements that emerged in the wake of the Titanic's sinking. From the introduction of double hulls in shipbuilding to the enhancement of lifeboat regulations and the establishment of an international ice patrol, these changes represented a collective effort to ensure that such a calamity would never happen again. The article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative impact of the Titanic disaster on the maritime industry, underlining the sacrifices made by those who perished and the advancements that were achieved to honor their memory.

The Tragic Memories invoked last week on the first anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic raise the question: To what extent, in these twelve months, have governments and steamboat companies applied the lessons driven home by that appalling disaster?

While some editors detect a tendency on the part of the public to forget those lessons and to relax the pressure of its demand for reforms, all agree that significant progress has been made in ocean travel safety. Today, we can confidently say that the safety of ocean travel is significantly improved, a testament to the terrible sacrifice of 1,503 men, women, and children in the icy waters of the North Atlantic in the early morning of 14 April 1912.

"The comparative safety of those who now go upon the sea in the great liners is the service done for them by the 1,500 souls lost with the Titanic," says the Springfield Republican, and in the Brooklyn Eagle, we read:

"Some good comes out of every great calamity, and some good has come out of this. We have abandoned as a fallacy the theory of the unsinkable ship. The preaching of many marine architects in favor of the double hull would not in a dozen years have carried the conviction at once brought home to shipbuilders when the full story of the wreck became known.

The agitation of legislative "reformers" worldwide would not have forced owners to increase their lifeboat and liferaft equipment so promptly as they did without compulsion when the Titanic tragically demonstrated the need for the increase.

Marconi himself could not have argued so forcefully for the perfection of wireless service at sea as did the want of a perfected system on ships that answered the Titanic's call for help. Suppose the catastrophe of 14 April 1912 is recalled with grief for those who perished bravely and uncomplainingly. In that case, people will also remember that the dead died not in vain."

According to the New York Times, perhaps the most crucial development in steamship building since the loss of the Titanic has been the double-skinned steamship, the ship within a ship, with transverse bulkheads extending between skins to the upper deck.

The new Hamburg-American liner Imperator, the largest vessel afloat, was designed and built on this principle, while the White Star liner Olympic, originally built with a single hull, has been reconstructed at the cost of a million and a quarter dollars, the principal change being the addition of inner skin.

Another result of the Titanic disaster, says The Times, has been to check the speed mania that had taken possession of both the traveling public and the steamship companies.

Moreover, an ice patrol has been established on the North Atlantic steamship lanes, the lifesaving equipment of the liners has been increased, and in some cases, two or more captains have been allotted to each ship so that the safety of the passengers shall not depend upon the judgment and alertness of an overworked officer.

The Imperator, for example, carries a commodore and three staff captains, one of whom will always be on the bridge. In the New York World, Mr. George Uhler, Supervising Inspector-General of the United States Steamboat Inspection Service, bears witness as follows to the increased precautions against disaster at sea:

"Since the Titanic went down, I have inspected many transatlantic liners, and I know of my knowledge that nearly every steamship landing at the port of New York now carries a sufficient number of lifeboats and rafts to care for every passenger on board in case these boats were called into use.

I also know that the officials of the major lines have cut down the number of passengers to be carried to fulfill promises made regarding a sufficient number of lifeboats for passengers and crew.

"It is likewise true that every large steamship now carries two wireless operators, one of whom shall be on duty constantly. As to the number of drills participated in by the crew, I also know that the companies are doing everything in their power to have the crew members so trained that all lifeboats and rafts may be adequately staffed and operated in cases of emergency. I cannot state how frequently these drills take place.

"Before the Titanic disaster, the question of boatage was regulated by the ship's tonnage, without regard for the number of the passengers. That has been changed; the number of boats now depends solely on the number of persons carried. Every American vessel engaged in overseas trade has boats and rafts to accommodate every person on board.

"In the lake, bay, and sound trade, passenger vessels must have lifeboats and rafts for all passengers only between 15 May and 15 September, when the passenger-carrying trade is greatest. During other seasons, they must have boats for but 60 percent of their passenger capacity. This is sufficient, for our coastwise passenger trade in the winter months is very light."

On 23 July 1912, the United States Congress passed a law forbidding any passenger ship, American or foreign, carrying fifty or more passengers to leave any American harbor without a wireless apparatus capable of transmitting and receiving messages a distance of one hundred miles, with an auxiliary power-plant sufficient to operate it for four hours if the primary machinery is disabled. At least two skilled men should be onboard to send messages.

In July of this year, an International Maritime Conference is expected to assemble in London to bring about an international agreement "for a system of reporting and disseminating information relating to aids and perils to navigation, the establishment of lane routes to be followed by the transatlantic steamers," and other matters affecting the safety of ocean travelers. Says The Times:

"Within the year, so many measures have been taken to guard against a repetition of this disaster that we may be sure that that type of disaster will not be repeated. No ship in the plight of the Titanic will be lost again under similar conditions."

"Fruits of the 'Titanic' Disaster," in The Literary Digest, New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, Vol. XLVI, No. 17, Whole No. 1201, 25 April 1913, p. 937-938.

Key Points

-

Introduction of the Double Hull Design:

- One of the most significant changes in shipbuilding following the Titanic disaster was the adoption of the double hull design. This "ship within a ship" concept provided an extra layer of protection against breaches and collisions.

- The new Hamburg-American liner Imperator was built with a double hull, while the White Star Line's Olympic, sister ship to the Titanic, was retrofitted with a new inner skin at a cost of over $1,000,000. This innovation reflected a shift towards more robust and secure shipbuilding practices.

-

Reform of Lifeboat Regulations:

- The article emphasizes the swift response to improve lifesaving equipment on ocean liners. Before the Titanic disaster, lifeboat capacity was determined by a ship's tonnage rather than the number of passengers. This policy was changed to ensure that there were enough lifeboats and life rafts for everyone on board.

- The United States Steamboat Inspection Service reported that transatlantic liners now carry a sufficient number of lifeboats and rafts for all passengers and crew, and the number of passengers carried was reduced to meet these new safety standards.

-

Enhanced Wireless Communication Requirements:

- Recognizing the critical role of wireless communication in emergencies, the United States Congress passed a law in July 1912 mandating that all passenger ships carrying fifty or more passengers must have wireless apparatus capable of transmitting messages over a distance of 100 miles. Additionally, ships were required to have at least two skilled operators onboard at all times.

- The presence of multiple wireless operators on ships ensured continuous monitoring and quick responses to distress calls, a lesson learned from the delay in the Titanic's communication.

-

Introduction of an International Ice Patrol and Route Adjustments:

- In response to the Titanic tragedy, an international ice patrol was established to monitor iceberg activity in the North Atlantic, providing early warnings to ships and helping them navigate safely.

- Steamship companies, in cooperation with the United States Hydrographic Office, agreed to move transatlantic routes approximately 100 miles further south, away from iceberg-prone regions, to avoid a repeat of the Titanic disaster.

-

Shift in Attitude Towards Speed and Safety:

- The disaster also tempered the "speed mania" that had gripped both the public and steamship companies. The emphasis shifted from breaking speed records to ensuring safer and more reliable ocean travel.

- New practices, such as assigning multiple captains or officers on ships like the Imperator, ensured that no single individual's judgment would determine a ship's safety, reducing the risk of human error due to fatigue or overwork.

-

International Efforts for Unified Maritime Safety Standards:

- The article notes the plans for an International Maritime Conference to be held in London in July 1913, aimed at developing an international agreement on safety practices, including lane routes for steamers and protocols for reporting navigational hazards.

Summary

The article "Fruits of the Titanic Disaster - 1913" provides a detailed account of the significant safety improvements and regulatory changes that emerged from the lessons learned after the sinking of the RMS Titanic. Among the most notable changes were the adoption of double hulls in shipbuilding, revised lifeboat regulations to ensure sufficient capacity for all passengers, enhanced wireless communication standards, and the establishment of an international ice patrol to monitor iceberg activity. These reforms marked a turning point in maritime safety, moving away from the reckless pursuit of speed towards prioritizing passenger safety and preparedness. The article highlights the progress made in the year following the disaster, underscoring that while the loss of life was tragic, it served as a catalyst for critical advancements that would protect future generations of ocean travelers.

Conclusion

The RMS Titanic disaster was a profound tragedy that left an indelible mark on maritime history, but it also led to some of the most significant reforms in ocean travel safety ever undertaken. As the article "Fruits of the Titanic Disaster - 1913" illustrates, the changes that followed—ranging from improved ship construction and lifeboat regulations to enhanced communication protocols and international collaboration—demonstrate a committed response to ensuring such a catastrophe would never occur again. The memory of the 1,503 men, women, and children who lost their lives in the icy waters of the North Atlantic continues to be honored through these advancements. The disaster of the Titanic has taught invaluable lessons that underscore the need for constant vigilance, innovation, and a shared responsibility in safeguarding human life at sea. As maritime travel continues to evolve, the legacy of the Titanic will remain a powerful reminder of the importance of prioritizing safety above all else.