Responsibility for the Titanic Disaster - 1912

Mr. Joseph Bruce Ismay - President of the International Mercantile Marine Company, testified before the investigation committee. He declares the wreck of the Titanic has taught him a lesson. The Literary Digest (4 May 1912) p. 917. © Underwood & Underwood. GGA Image ID # 103a71ff4f

Introduction

The catastrophic sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912, has raised profound questions about responsibility and accountability. The article "Responsibility for the Titanic Disaster - 1912" from The Literary Digest delves into the investigations led by the United States Senate and the British government to determine the causes of the disaster and identify those at fault. With the loss of over 1,500 lives, there is a worldwide demand for answers regarding what went wrong and who is to blame. The article explores the roles of key figures such as Captain Edward Smith, the ship's captain, and J. Bruce Ismay, President of the International Mercantile Marine Company, which owned the Titanic. It also examines the broader responsibilities of the White Star Line and the regulatory bodies overseeing maritime safety. Through a detailed examination of testimonies and editorial commentary, the article highlights the complexity of assigning blame and the urgent need for systemic reforms to prevent future maritime tragedies.

While a particular element of mystery must always shroud the loss of the Titanic, the ongoing investigation is shedding light on many aspects. Specific facts are known only to the deceased Captain and first officer, and others are hidden forever in her rent hull two thousand fathoms deep. However, much is also being cleared up by the patient and thorough investigation, and the press is diligently sifting these facts and placing the blame.

The world is demanding to know where to put the responsibility; it is correcting false rumors and seeking all information that would help make ocean travel safer. The public's role in this quest for accountability is crucial, and its demand for transparency is driving the investigation forward.

Therefore, a committee of the United States Senate, known for its rigorous investigative procedures, is currently hearing testimony from survivors and officials of the White Star Line. Additionally, the British government, renowned for its thoroughness, is set to institute a similar inquiry, ensuring a comprehensive investigation.

As the passengers, officers, and members of the crew tell their following stories and answer the searching questions of the investigators, the horror of the Titanic's sinking, it is remarked, only deepens. The needless loss of life becomes more and more apparent, and the audience's empathy for the victims and their families grows.

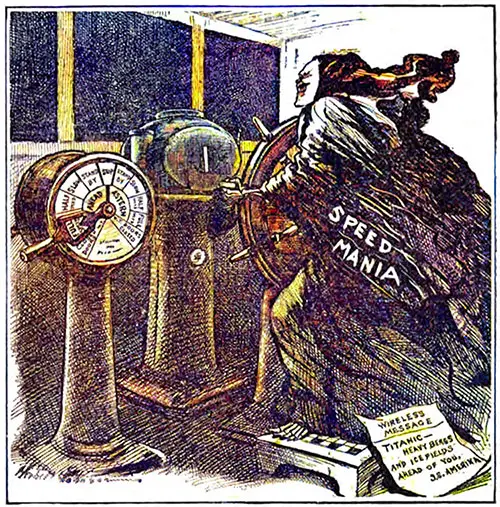

Back at high speed in an ice-infested sea and back to the lack of lifeboats, another reason was becoming more apparent to the press daily. To the New York Tribune, this is the only theory upon which the various elements of the disaster are explicable.

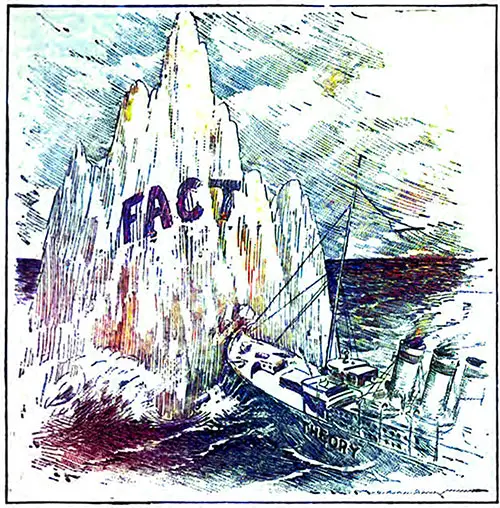

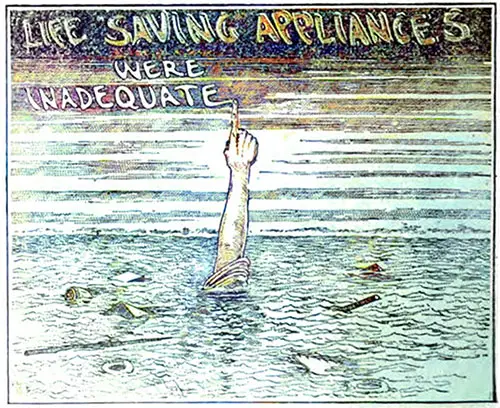

Passengers, proprietors, and officers alike were obsessed with the infatuation that the ship was unsinkable. With her watertight compartments, the safety of the modern all-steel liner had kept the British Board of Trade content with an inadequate life-saving requirement.

The owners of the Titanic had been content with complying with the law, though it meant refuge for less than half of those on board. Because, as Captain Rostrom of the Carpathia crisply puts it, the Titanic was supposed to be a lifeboat herself.

The alleged lack of vigilance before the collision, the failure to fill the lifeboats to their capacity, and the holding back of the news of the ship's loss are all ascribed to a persistent and fatal belief that the Titanic was unsinkable. This belief, deeply ingrained in the minds of passengers and crew alike, led to a complacency that proved to be fatal.

As the Army and Navy Journal (New York) remarks, 'Out of the fabric of its delusion and hope, the public created the unsinkable boat and confided itself blindly in it despite warnings that even a child might have listened to.' This 'fabric' refers to the collective optimism and trust in technological advancements that led to the creation of the unsinkable myth, a belief that was tragically shattered on that fateful night.

The Helmsman—Johnson in the Philadelphia North American. The Literary Digest (4 May 1912) p. 921-b. GGA Image ID # 103a800831

But people are not content with knowing what is responsible. Responsibility is personal, we are reminded, and the question is, Who? And two persons are named: Captain Smith and J. Bruce Ismay.

The Captain went down with his ship, and many are inclined to cover him with the mantle of charity and remember only his heroic end. However, the Albany Journal and the New York Times are among the papers that can not absolve Captain Smith of blame.

Says The Times: Ice, floating ice, and bergs were in plain sight. Not only that, but Captain Smith had received at least three warnings by wireless messages that icebergs were in his path—from the Touraine, the Amerika, and the Mesaba. He had acknowledged with thanks the Mesaba's warning that dead ahead of him lay much heavy-packed ice and significant numbers of bergs. Yet straight into the jaws of destruction, he steamed at high speed.

The company is by no means to be absolved. Undoubtedly, the Captain was aware of a desire on the company's part for a short voyage. It would please the passengers and bring trade to the line.

But no orders from the company compel, and its desires should not persuade a captain to steam through a field of icebergs at 21 knots an hour. The responsibility of the wreck rests upon the Titanic's Captain directly and secondarily upon the owners.

Though The Times gives the White Star Line, or the International Mercantile Marine Company which controls it, a secondary responsibility, most of its contemporaries assign it the first, and some the only, place among the guilty.

Captain Rostrom, they recall, admitted when questioned that under the law, a captain's control over his ship is absolute. Then he added: But suppose we get orders from our boat owners to do a certain thing. We are liable to dismissal if we do not execute that order.

Captains should exercise the utmost care, but the Springfield Republican observes that they should also improve their boats' speed and regularity or appoint a more competent man.

Under this pressure, if not admitted, a commander must often be obliged to take risks not less real but intangible. Though expensive, speed is safe enough; what is extremely dangerous is the demand for speed combined with a high degree of regularity.

A captain ought to be free and, in theory, to use his best judgment, even if a four-day crossing should be stretched out to a fortnight.

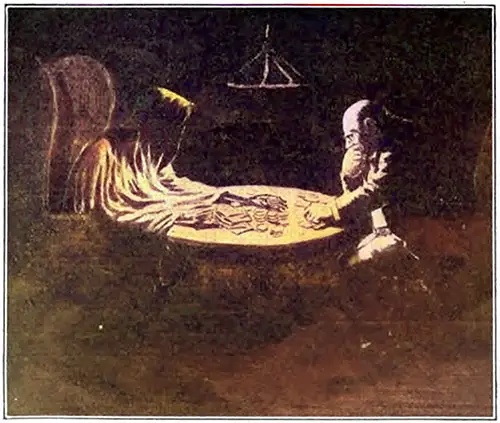

Special reasons for desiring a quick and splendid run on the Titanic's maiden trip are found daily in the company's financial condition.

The Republican notes that International Mercantile Marine bonds have paid interest charges, but investors in the company's preferred and common shares have never received a dividend.

The White Star Line's common stock sold as low as 5 (par value 100) and the preferred stock at 26 before the Titanic disaster. Reorganization is said to be imminent.

The Wall Street Journal confirms these statements, remarking on a movement to stimulate speculation in the stock. Part of the campaign plan was alleged to be to interest the public in the successful maiden trip of the Titanic. Such plans miscarried.

The Eternal Collision —Macauley in the New York World. The Literary Digest (4 May 1912) p. 921-a. GGA Image iD # 103ac3fcc9

The criticisms of J. Bruce Ismay, the responsible head of the White Star Line and the company owning it for saving his own life, have been stilled somewhat by sworn testimony justifying his act. However, there is still an inclination to make him a scapegoat.

Senator Smith's insistence on keeping him in this country to give testimony concerning the disaster is one of the matters that has prompted caustic comments from the British press on the conduct of the Senatorial investigation. The Hearst papers, the Philadelphia North American, and other journals see his presence on the Titanic as proof of his authority there.

At least, thinks the Baltimore News, his word would weigh with the Captain, who told him of one of the iceberg warnings, so that The News finds it difficult to believe that one word of caution from Mr. Ismay to the effect that the Titanic would better come into New York behind schedule time than to hit an iceberg would not have been taken even by the most autocratic Captain as a hint not to be disregarded.

Mr. Ismay's statement is at least clear and consistent. But other papers are beginning to agree with the Louisville Courier-Journal that something is to be said for him. He says in part:

When I boarded the Titanic at Southampton on 10 April, I intended to return by her. I had no intention of remaining in the United States at that time. I came merely to observe the new vessel, as I had done with other lines' ships.

I was a passenger during the voyage and exercised no greater rights or privileges than any other passenger. The commander did not consult me about the ship, course, speed, navigation, or conduct at sea; all these matters were under the exclusive control of the Captain.

As other passengers did, I saw Captain Smith only casually. Captain Smith or any other person never consulted me, nor did I make any suggestions to anyone about the ship's course.

The only information I ever received on the ship that other vessels had sighted ice was by a wireless message from the Baltic.

If the information received had aroused any apprehension in my mind—which it did not —I should not have ventured to suggest to a commander of Captain Smith's experience. The responsibility for the navigation of the ship rested solely with him.

Everybody learns by experience, observes Mr. Ismay. He believes that in this crisis, the steamship owners of the world have realized that too much reliance has been placed on watertight compartments and wireless telegraphy and that they must equip every vessel with lifeboats and rafts sufficient to provide for every soul on board and adequate men to handle them.

They have learned, too, that there are, at present, no such things as unsinkable ships. As the first result of this lesson, Mr. Ismay has ordered that all vessels belonging to the International Mercantile Marine Company shall be fully equipped with lifeboats. In announcing this decision, he says:

I am candid to admit that until I had experience in a wreck, I never fully realized the inadequacy of the rules of our and other lines concerning preserving life in case of an accident in mid-ocean. I had gone along like the other steamship men on the theory that our ships were unsinkable.

I am determined to do this irrespective of any present or future laws on the subject, either in this country, in England, Holland, or any other foreign country touched by the lines of the International Mercantile Marine Company.

I will see that not only every passenger but every crew member on any ship of the White Star, the American, and all other lines of the International Mercantile Marine shall be as safe as possible in case of another accident.

The Steamship-owner Gambled with Death - But Death held the cards —Barclay in the Baltimore Sun. The Literary Digest (4 May 1912) p. 920-a. GGA Image ID # 103c61ea80

We are not waiting to comply with the law only. We will disregard technicalities and give human life the amplest and complete protection, irrespective of all legal requirements.

In the future, there will never arise a condition in which there is no room for everybody in the lifeboats or on the unsinkable pneumatic life-rafts incapable of being upset in rough weather.

Similar action has been taken by other steamship lines so that the New York Sun thinks it safe to say that never before in the history of the mercantile marine of any nation have life-saving appliances aboard a ship been brought to their maximum efficiency so quickly as has been done by all countries since the Titanic disaster taught its tragic lesson.

Immediately after the first report of the accident to the Titanic, the steamship companies conferred with the United States Hydrographic Office, and all captains were instructed to take a new southern route. This route was intended to bring them many miles south of the iceberg zone, though it added 200 miles to the westbound course.

Moreover, notes The Sun, the ships are going out equipped with more lifeboats than ever, and these boats are ready for service.

A remarkable instance of the effect of the Titanic's loss was the mutiny of the crew of her sister ship, the RMS Olympic. The firemen distrusted the collapsible boats furnished to complete her equipment, causing the scheduled trip from Southampton to New York to be abandoned last week.

In addition to the steps taken by the shipping companies, Great Britain, the United States, and other maritime powers, we will make their respective regulations stricter and enforce more careful inspection.

Soon, an international conference will be held to recommend uniform legislation on the problem of ensuring the safety of steamers and on similar matters.

The Moving Finger Writes, And. Having Writ, Moves On. (Life Saving Appliances Were Inadequate —Ireland lo the Columbus Dispatch. The Literary Digest (4 May 1912) p. 920-b. GGA Image ID # 103c9aff7e

While it is universally acknowledged that the Titanic disaster taught one valuable lesson: the priceless worth of wireless communication at sea, it is no less generally felt that the wireless system has fallen short of its possibilities due to a lack of systematized organization and cooperation, as the Baltimore Sun puts it, in connection with the recent disaster.

True, the Carpathia heard the distress call, but only because the single operator had postponed his usual hour of retirement by chance. Another ship that might have come up in time to save all the passengers failed to receive the call from the Titanic because the operator was asleep. Hence, there is a strong demand for some regulation providing wireless outfits on freight and passenger steamers and requiring every passenger boat to carry two operators.

Then, too, the confusion regarding the messages from the Carpathia, other vessels, and stations on shore, accusations of holding up messages, and refusals of operators on rival lines to communicate courteously with each other bring forth such indignant editorial comments as this in the New York World:

One reform made mandatory by the Titanic disaster is the immediate systematization of wireless communication at sea and its regulation in the public interest. The revelation of lax and chaotic wireless communication methods on the ocean should lead to a reform that must secure stricter regulation for the public benefit under international agreements, providing for its more responsible control.

Meanwhile, the Senate's committee is carrying out a thorough investigation. It comprises Senators Smith of Michigan, Chairman; Perkins of California; Bourne of Oregon; Burton of Ohio; Fletcher of Florida; Simmons of North Carolina; and Newlands of Nevada.

According to Senator Smith, the purpose of the inquiry is to get all facts bearing upon this unfortunate catastrophe that we can obtain. The detention of Mr. Ismay and officers and members of the crew of the Titanic, which has been criticized in England, is thus explained by Senator Smith:

From the beginning, we have planned to temporarily obtain the testimony of citizens or subjects of Great Britain in this country. The committee will pursue this course until we conclude it has obtained all accessible and valuable information to understand this disaster properly.

Members of the committee, particularly Mr. Smith, are criticized because of their unfamiliarity with the subject. The British press sneers at them and expresses surprise that the Senate did not leave such matters to a committee of experts. Some of this harsh criticism our press finds to be deserved.

The Springfield Republican's Washington correspondent admits that the investigation is ludicrous and that the committee chairman, in particular, shows "remarkable persistence and fertility in asking ignorant questions.

The Senate's hasty action in starting the investigation, which began the morning after the Carpathia reached New York, has been condemned by the English press and by speakers in the House of Commons.

But our papers praise such timeliness, and it will, thinks the New York American, spur the English themselves to quicker and more resolute action than they otherwise would have been likely to take.

The further assertion that the United States Senate has no right to conduct such an inquiry about the disaster that had occurred on a British ship on the high seas is thus answered by the New York Tribune.

The Titanic inquest is being held here because, as one of the members of Parliament suggested yesterday, many American citizens lost their lives in the disaster. Nor can there be any valid denial of the right of this Government to investigate the equipment and conduct of foreign ships that seek the use of its ports and the patronage of its citizens and, in so doing, to ask questions of any of the alien owners and officers of those ships whom it may happen to find within its jurisdiction.

"Topics of the Day: Responsibility for the 'Titanic' Disaster," in The Literary Digest, New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, Vol. XLIV, No. 18, Whole No. 1150, 4 May 1912:917-920.

Key Points

-

The Role of Captain Edward Smith:

- Captain Edward Smith, who went down with the Titanic, is a central figure in the discussion of responsibility. Critics argue that Smith ignored multiple warnings about icebergs in the vicinity and maintained a high speed of 21 knots, believing in the ship's unsinkability.

- While some defend Smith's actions, suggesting he may have been under pressure from the company to make a fast voyage, others, including the New York Times, hold him directly responsible for recklessly navigating through a known ice field.

-

Criticism of J. Bruce Ismay and the White Star Line:

- J. Bruce Ismay, President of the International Mercantile Marine Company and a passenger on the Titanic, faced widespread criticism for surviving the disaster while many others perished. His presence on the ship is seen by some as evidence of his influence over its operations.

- Ismay defended his actions by stating he had no authority over the ship's navigation or speed and was merely a passenger. Nonetheless, his decision to board a lifeboat while others remained on the sinking ship led to accusations of cowardice and negligence.

-

The Flawed Belief in an "Unsinkable" Ship:

- A recurring theme in the article is the widespread belief in the Titanic's unsinkability, a delusion shared by passengers, crew, and company officials alike. This belief contributed to complacency in safety measures, such as the inadequate number of lifeboats and the failure to fill them to capacity during the evacuation.

- The Army and Navy Journal emphasizes that this misplaced confidence led to a failure to heed warnings and prepare adequately for emergencies, contributing to the high loss of life.

-

The Pressure for Speed and Financial Motives:

- The article highlights the pressure on captains to maintain speed and regularity to attract business and meet financial goals. The White Star Line and the International Mercantile Marine Company were reportedly in a difficult financial situation, adding urgency to make the Titanic's maiden voyage a success.

- Editorials such as the Springfield Republican suggest that economic pressures and the desire to stimulate stock market interest may have influenced decisions made during the voyage, including ignoring ice warnings.

-

Critique of the Investigations and Media Coverage:

- The U.S. Senate's investigation, led by Senator Smith, faced criticism for its lack of maritime expertise and the conduct of its questioning. The British press and public opinion questioned the legitimacy of the American inquiry, given that the disaster occurred on a British ship in international waters.

- Despite the criticism, the investigations played a crucial role in uncovering the flaws in safety practices and catalyzing reforms in maritime regulations, particularly concerning lifeboats and wireless communication.

-

Call for Systematic Reforms in Maritime Safety:

- The article discusses the immediate steps taken by shipping companies, such as the International Mercantile Marine Company, to increase the number of lifeboats and implement more rigorous safety measures on their vessels.

- There is also a call for international cooperation to establish uniform maritime safety regulations, ensuring that ships are adequately equipped and prepared to handle emergencies.

Summary

The article "Responsibility for the Titanic Disaster - 1912" explores the ongoing investigations into the Titanic's sinking and the search for accountability. It highlights the criticisms leveled against Captain Edward Smith and J. Bruce Ismay, the president of the company that owned the Titanic, and examines the broader responsibilities of the White Star Line and the maritime regulatory bodies. The article underscores the deadly consequences of the misplaced belief in the Titanic's unsinkability, the economic pressures driving risky navigation decisions, and the need for substantial reforms in maritime safety practices. It emphasizes the importance of holding individuals and institutions accountable while calling for systematic improvements to prevent future disasters. The article ultimately argues for greater transparency, regulation, and international cooperation to ensure the safety of ocean travelers.

Conclusion

The RMS Titanic disaster remains one of the most poignant reminders of the fallibility of human decision-making and the dangers of overconfidence in technology. As the article "Responsibility for the Titanic Disaster - 1912" reveals, determining responsibility for the tragedy is complex, involving multiple parties, including Captain Smith, J. Bruce Ismay, the White Star Line, and the regulatory bodies overseeing maritime safety. The sinking of the Titanic exposed significant flaws in safety protocols, driven in part by economic motives and a reckless belief in the ship's invulnerability. The subsequent investigations by the U.S. Senate and the British government were not without controversy, but they were crucial in driving reforms that have since reshaped maritime safety standards. The article emphasizes that while individual accountability is necessary, systemic changes are vital to ensure such a disaster is never repeated. The Titanic's legacy serves as a powerful reminder of the need for vigilance, caution, and continual improvement in maritime safety practices.