The International Ice Patrol

Official Coast Guard Photo. Thirty-Four Years Ago Today (14 - 15 April 1912), 1,517 Men, Women, and Children Lost Their Lives When the Beautiful, Shining New Titanic, on Her Maiden Voyage, Crashed Her “Unsinkable” Bow Into Just Such a Floating Giant. Coast Guardsmen Aboard a Cutter Attached to the International Ice Patrol Pay Slight Attention to a Huge Iceberg Floating by. The Patrol Had Already Warned All Shipping of Its Location and Direction of Drift. Record Group 26: Records of the U.S. Coast Guard, Series: Photographs of Activities, Facilities, and Personalities, File Unit: International Ice Patrol. NAID: 205581387. Local ID: 26-G-01-24-46(1). Produced: January 24, 1946. GGA Image ID # 21a10a9669

Introduction

The sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912 was one of the deadliest maritime disasters in history, profoundly impacting global maritime safety regulations. In the aftermath of this tragic event, the need for a systematic and reliable way to monitor and report iceberg dangers became evident. The result was the establishment of the International Ice Patrol (IIP) in 1914, a service dedicated to ensuring the safety of transatlantic ships navigating through iceberg-prone waters. Created as part of an international effort to prevent a recurrence of such a tragedy, the IIP represents one of the most significant advancements in maritime safety. This article explores the origins, operations, and continued relevance of the International Ice Patrol, highlighting its role in transforming transatlantic ocean travel and its enduring commitment to protecting lives at sea.

U.S. Coast Guard, Washington, DC, Release of Official US Coast Guard Photograph, Taken Aboard a Coast Guard Cutter Assigned to the International Ice Patrol, 12 April 1944. GGA Image ID # 21a1f02297

The International Ice Patrol (IIP) is an organization established to monitor and report the presence of icebergs in the North Atlantic Ocean, particularly in the shipping lanes used by vessels traveling between Europe and North America. Its creation is directly linked to the tragic sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912. Here is an overview of the IIP, its history, its connection to the Titanic disaster, and its role today:

Overview of the International Ice Patrol (IIP)

- Founded: 1914

- Purpose: To monitor iceberg danger in the North Atlantic Ocean and provide safety information to transatlantic ships.

- Administered by: United States Coast Guard

- Operations: Primarily conducted through aerial reconnaissance and, more recently, satellite imagery.

Link to the Titanic Disaster

The formation of the International Ice Patrol is a direct result of the sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912. Here’s how the disaster influenced its creation:

-

Titanic’s Collision with an Iceberg: The Titanic, on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York City, collided with a large iceberg in the North Atlantic. The collision resulted in the ship sinking, leading to the loss of over 1,500 lives.

-

Lack of Iceberg Monitoring: Before the Titanic disaster, there was no formalized system for monitoring and reporting iceberg locations in the shipping lanes of the North Atlantic. Ships relied on occasional reports from other vessels, which often led to insufficient or outdated information.

-

International Response: The tragedy highlighted the need for a dedicated service to track icebergs and warn ships. As a result, during the first International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in London in 1913, several countries decided to establish the International Ice Patrol.

Establishment and Early History

-

Official Formation: The IIP was officially established in 1914 under the auspices of SOLAS, and its operation was assigned to the United States. Since then, it has been funded and supported by various countries whose ships pass through the North Atlantic shipping lanes.

-

Initial Operations: Early operations of the IIP were carried out using ships equipped with radio communication systems to locate and report iceberg positions. Cutters from the U.S. Coast Guard were initially used to patrol the ice-prone regions.

-

Aerial Reconnaissance: In the 1920s and 1930s, the IIP began employing aircraft for aerial reconnaissance of icebergs, greatly enhancing its ability to detect and track icebergs. This shift allowed for more comprehensive coverage and timely information dissemination to ships.

Modern Operations

-

Technology and Methods: Today, the International Ice Patrol utilizes advanced technology, including satellite imagery, GPS, radar, and aircraft equipped with sensors to detect icebergs. These advancements have made iceberg detection and tracking much more precise and efficient.

-

Area of Operations: The IIP focuses on the waters off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, particularly in the region known as the "Iceberg Alley"—a major transatlantic shipping route where the Labrador Current carries icebergs from the Arctic southward into the Atlantic Ocean.

-

Iceberg Bulletins and Warnings: The IIP issues daily iceberg bulletins and warnings from February through August, the period when icebergs are most prevalent. These bulletins are distributed to ships and maritime organizations worldwide.

Impact and Safety Record

-

Improved Maritime Safety: Since its establishment, the IIP has contributed significantly to maritime safety in the North Atlantic. There has not been a single reported loss of life or major ship damage due to iceberg collision in areas monitored by the IIP since its inception.

-

International Collaboration: The IIP operates as a collaborative effort involving multiple countries, ensuring safety in international waters. Countries benefiting from the IIP services contribute to its funding.

Legacy and Importance

-

Preventing Another Titanic: The International Ice Patrol stands as one of the most enduring legacies of the Titanic disaster. It was created to prevent similar tragedies and ensure safe passage for ships crossing the North Atlantic.

-

Continued Relevance: Despite over a century of operation, the IIP remains highly relevant due to changing climate conditions, which may affect iceberg formation and drift patterns. It continues to adapt its methods to the evolving technological landscape and environmental challenges.

Conclusion

The International Ice Patrol is a prime example of how a catastrophic event like the sinking of the Titanic led to substantial international cooperation and innovation in maritime safety. The IIP has played a crucial role in protecting lives and property at sea for over a century, providing a model of how proactive measures can mitigate natural hazards in critical shipping lanes.

Official U.S. Coast Guard Photograph Rel. No. 6056 In Recognition of the Coast Guard Operatin the International Ice Patrol for Half a Century, 1 March 1964. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 26: Records of the U.S. Coast GuardSeries: Photographs of Activities, Facilities, and PersonalitiesFile Unit: International Ice Patrol. BAUD 205581624, Local ID 26-G-6056. GGA Image ID # 21a1bb5039

A U.S. Coast Guard HC-1308 "Hercules" Plane Tracks an Iceberg in the Grand Banks Region During a Recent Ice Patrol Flight, February 1964. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 26: Records of the U.S. Coast Guard. Series: Photographs of Activities, Facilities, and Personalities. File Unit: International Ice Patrol. NAID: 205581624. Local ID: 26-G-6056. Photographs and other Graphic Materials -- 2 Images. GGA Image ID # 21a1c81cdf

Original caption:

Aerial ice reconnaissance work of the International Ice Patrol is performed in 1964 by U.S. Coast Guard turbine-powered four-engine HC-130B "Hercules" planes based at Argentia, Newfoundland. Here a "Hercules" tracks an iceberg in the Grand Banks region during a recent Ice Patrol flight.

The first aerial ice scouting flights started during the 1946 International Ice Patrol season. Within a period of forty-four days of that season, seventy-one flights frequently averaging eight to ten hours long were performed by Catalinas, Liberatos and converted B-17 "Flying Fortresses" of World War II Fame.

Operations improved so noticeably that since that time the Ice Patrol has relied mainly on aerial reconnaissance flights. Coast Guard cutters which had solely performed the work of tracking icebergs and warning ships passing through the dangerous ice zone of the North Atlantic from the formal inception of the Ice Patrol in 1914 until 1941, were relegated to standby duty.

Only in emergencies are Coast Guard cutters now used on Ice Patrol reconnaissance as when icebergs drift too near the shipping lanes and require constant monitoring. Also when the patrol planes are grounded because of dense fog or foul weather.

The Story of the ICE PATROL

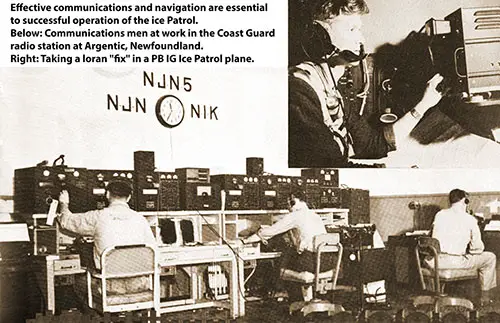

Effective Communications and Navigation Are Essential to Successful Operation of the Ice Patrol. Below: Communications Men at Work in the Coast Guard Radio Station at Argentic, Newfoundland. Right: Taking a Loran “Fix” in a PBIG Ice Patrol Plane. International Ice Patrol, USCG Brochure, 1956. GGA Image ID # 21a1d7d075

For many years, trans-Atlantic navigators have dreaded icebergs along the tracks near the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. In the days of slow steamers, most vessels took a course directly across the Banks, carrying them through the ice zone for most of the year.

Since the advent of large and fast steamers, agreements have been entered, and definite routes have been established southward of the normal ice zone. If the ice zone were fixed, nothing would be required to assure reasonable safety along these routes. Unfortunately, the limits of the ice fields and bergs vary considerably in their location during and from season to season.

Consequently, a vessel might sail on a clear course at her departure but encounter ice that had drifted into her path before she reached the Grand Banks. This historical context underscores the significance of the Ice Patrol's establishment.

Arctic ice drifts southward into the North Atlantic Ocean every spring and summer and presents a menace to ships traversing the ocean north of 40° latitude.

The ice menace is greatest off Newfoundland, where the prevalence of fog is added to the accumulation of icebergs, the concentration of traffic, and the presence of fishing vessels scattered over the Grand Banks. All these factors have contributed to the likelihood of collision in the Western North Atlantic.

A perusal of the history of navigation before the turn of the twentieth century impresses one with the many casualties that befell vessels in the above waters. Collisions between east- and westbound ships first claimed more attention than the perils of ice.

It was in 1855 that Matthew Fontaine Maury, in his Sailing Directions, proposed separate lane routes, with the eastbound lane just south of Cape Race and the westbound lane near the tail of the Grand Banks. Serious mishaps with ice continued to be frequent until 1875, when the Cunard Line adopted a system of tracks, the southern ones being laid south of the normal ice limits. The added safety of these precautions caused other large companies to join with the Cunard Line in adopting 1898 the present North Atlantic Track Agreement.

The Sinking of the RMS Titanic and Aftermath

Previous to 1912, nothing had been done toward the establishment of any system for guarding against the danger from floating ice along the trans- Atlantic steamship lanes in the vicinity of the Grand Banks, off Newfoundland, but on April 14 of that year, when the steamer Titanic was sunk by striking an iceberg, there arose an almost universal demand for a patrol of the ice zone to warn passing vessels of the limits of danger from day to day during the season. Two Navy scout cruisers patrolled the ice regions throughout the dangerous periods of that year. During the 1913 season, the patrol was undertaken by the Treasury Department and performed by the Coast Guard cutters Seneca and Miami.

The British Government also played a significant role in addressing the ice observation and ice patrol issue. In 1913, they chartered and equipped the steam trawler Scotia for this service, with the cost shared by the British Board of Trade and various British trans-Atlantic steamship companies.

The Scotia's work primarily involved ice and weather observations off the coast of Newfoundland. Despite being hindered by fog and storms, it still managed to gather valuable information and cooperated with the US Coast Guard cutters in disseminating ice information to passing vessels.

Patrolling the ice regions was thoroughly discussed at the International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea, convened in London on November 12, 1913. The convention signed on January 30, 1914, by the representatives of the various maritime powers of the world, provided for the inauguration of an international derelict destruction.

An ice observation and ice patrol service, consisting of two vessels, should patrol the ice regions during the season of danger from icebergs and attempt to keep the trans-Atlantic lanes clear of derelicts during the remainder of the year. This international cooperation is a testament to the unity and collaboration among maritime powers in ensuring trans-Atlantic navigation safety.

As the convention, when ratified, would not go into effect until July 1, 1915, the government of Great Britain, on behalf of the several powers interested, inquired on January 31, 1914, as to whether the United States would be disposed to undertake the work at once under the same mutual obligations as provided in the convention.

The President favored the proposition, and on February 17, 1914, he directed that the (then) Revenue Cutter Service begin the international ice observation and ice patrol service as early as possible in that month. This commitment to the Ice Patrol's mission has been unwavering, with a patrol maintained by the Coast Guard each year since then, except for the World War years of 1917 and 1918.

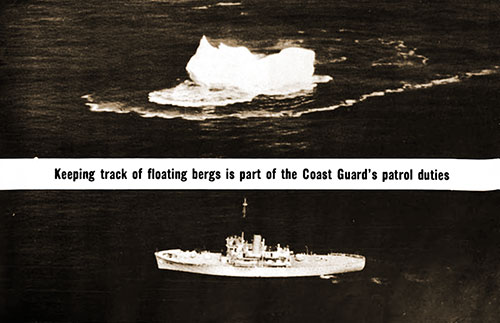

Keeping Track of Floating Bergs Is Part of the Coast Guard’s Patrol Duties. International Ice Patrol, USCG Brochure, 1956. GGA Image ID # 21a1eb5cb9

The second International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea, convened in London on April 16, 1929, was another significant event in the Ice Patrol's history. Eighteen nations participated, signing the final act on May 31, 1929. However, due to concerns in the United States Senate about ambiguities in Article 54 dealing with control, the 1929 convention was not ratified by the United States until August 7, 1936.

Even then, the ratification was accompanied by three reservations. At the same time, Congress enacted legislation on June 25, 1936, requiring the Commandant of the Coast Guard to administer the International Ice Observation and Ice Patrol Service (ch. 807, par. 1, 49 Stat. 1922) and prescribing in a general fashion how this service was to be performed. Today, This remains the essential Coast Guard authority to operate the International Ice Observation and Ice Patrol Service.

Due to the advances in nautical science and the improved techniques developed during World War II, a third convention was felt obligatory to be convened as soon as practicable after the close of hostilities. A special shipping committee organized by that department made such a recommendation to the Secretary of State in 1943.

The Secretary of State approved this recommendation, and the Coast Guard Commandant was instructed to draw up a set of United States proposals to revise the 1929 convention. In an informal conversation between the United Kingdom and the United States, it was agreed that the United Kingdom would, by the provisions of the 1929 convention, invite those nations' parties to attend a conference for its revision. Accordingly, a conference was convened in London on April 23, 1948. This conference resulted in the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1948, signed on June 10, 1948, and ratified without amendment by the United States Senate on April 20, 1949.

According to the convention's provisions, it was to come into force on January 1, 1951, provided that at least 12 months before that date, not less than 15 acceptances, including seven by countries, each with not less than 1 million gross tons of shipping, were deposited. It was not until November 19, 1951, however, that the required 15 acceptances were deposited, and the 1948 convention came into force on November 19, 1952.

The funding of the International Ice Patrol is computed by determining the total tonnage of each signatory nation passing through the ice patrol area and by distributing the cost of the operation in proportion to the tonnage as a whole. In other words, the patrol is financed on a "pay-as-you-benefit" basis.

As of early 1956, the governments contributing to the Ice Patrol included the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Greece, Netherlands, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.

To summarize, the present United States responsibility to manage and contribute to the cost of the International Ice Observation and Ice Patrol Service is contained in the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1948, and the present Coast Guard responsibility and authority to conduct the service is included in 14 U. S. C. 738 (ch. 804, par. 1, 49 Stat. 1922).

United States Coast Guard, "The Story of the ICE PATROL," in "International Ice Patrol," Washington, DC: Public Information Division, Brochure CG-171, October 1957, (Unpaginated).

Key Points

-

Origins and Formation of the International Ice Patrol:

- The IIP was established as a direct response to the sinking of the RMS Titanic, which struck an iceberg in April 1912, resulting in the loss of more than 1,500 lives.

- At the first International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in 1913, several nations came together to create the International Ice Patrol, tasked with monitoring and reporting the presence of icebergs in the North Atlantic.

- The United States was given the responsibility to manage and operate the IIP, primarily funded by countries with ships navigating through these waters.

-

Early Operations and Techniques:

- Initially, the IIP relied on Coast Guard cutters and ships to patrol the seas and observe iceberg locations. These ships reported their findings via radio to warn nearby vessels.

- The early years of the IIP saw advancements in communication and observation techniques, including the use of radar and sonar, which significantly improved the accuracy and efficiency of iceberg tracking.

-

Technological Advancements and Modernization:

- Over the decades, the IIP has incorporated modern technologies such as aerial reconnaissance, satellite imagery, and advanced computer models to predict iceberg drift patterns and movements.

- These technological advancements have enhanced the IIP's ability to provide real-time data and forecasts, ensuring a higher level of safety for ships navigating through potentially hazardous waters.

-

Impact on Maritime Safety and International Collaboration:

- Since its inception, the IIP has played a critical role in maritime safety, and there has not been a single reported loss of life due to an iceberg collision in the areas monitored by the IIP.

- The IIP represents a significant international collaboration, with numerous countries contributing to funding and operational support. Its work is a testament to the effectiveness of coordinated international efforts in addressing global safety challenges.

-

Enduring Legacy and Relevance Today:

- The IIP continues to operate under the U.S. Coast Guard, using cutting-edge technology to track and report iceberg locations. It remains a vital service that has adapted to the changing environment and continues to prioritize safety at sea.

- The organization’s adaptability and commitment to innovation ensure it remains relevant in an era where climate change may impact iceberg patterns and sea conditions.

Summary

The article on the International Ice Patrol highlights its crucial role in enhancing maritime safety following the Titanic disaster in 1912. Established in 1914 through international cooperation and led by the United States, the IIP's primary mission is to monitor and report iceberg dangers in the North Atlantic shipping lanes. Over the years, the IIP has evolved from using basic ship-based observations to employing advanced aerial reconnaissance, satellite imagery, and predictive modeling technologies. These advancements have significantly improved its effectiveness in safeguarding transatlantic ocean travel. The IIP's success is evident in its impeccable safety record, with no reported losses of life due to iceberg collisions in monitored areas since its formation. The article underscores the enduring significance of the IIP as a symbol of international collaboration, innovation, and a relentless commitment to safety at sea.

Conclusion

The establishment and evolution of the International Ice Patrol stand as one of the most remarkable achievements in the history of maritime safety. Born out of the tragedy of the Titanic, the IIP has continuously adapted to technological advancements and changing environmental conditions to protect lives at sea. It exemplifies how international cooperation and innovative practices can effectively address global challenges and ensure safer transatlantic travel. As the threat of climate change looms over ocean navigation and iceberg dynamics, the International Ice Patrol's role remains more vital than ever. Its commitment to leveraging cutting-edge technologies and maintaining a high standard of vigilance will continue to be essential in safeguarding maritime routes and preserving the lessons learned from history.