The Titanic Horror - April 1912

View of the RMS Titanic, 15 Minutes Before She Sank. The Illustrated London News (18 May 1912) p. 748-749. GGA Image ID # 1011850432

Introduction

"The Titanic Horror," published in American Medicine in April 1912, is an emotionally charged reflection on the tragic sinking of the RMS Titanic, an event that shocked the world. This article captures the magnitude of the catastrophe, depicting the unexpected demise of what was believed to be the most advanced and "unsinkable" ship of its time. The narrative offers a poignant blend of grief, admiration, and critique, reflecting on the human and technological failings that contributed to the disaster and honoring the heroism displayed during the tragedy. Moreover, it delves into the broader lessons that society must learn from this event, particularly regarding humility in the face of nature's power, the prioritization of safety over speed, and the ethical responsibilities of humanity.

The Titanic horror fills everyone with an indescribable sadness. In recent years, hardly any great calamity has been so startling or exemplified so thoroughly that we are in death amid life.

Imagination runs rife, and the scenes that picture themselves on the tablets of our minds are almost too terrible to describe.

Here was the last word in boat construction, a masterpiece from every standpoint—size, convenience, equipment, luxury, and safety. With apparently every known device for protection against every force of the sea, if there was ever an unsinkable boat, the Titanic was the one.

Representing the length and breadth of man's latest knowledge of shipbuilding, the current estimate of this magnificent vessel's fitness to triumph over every danger is shown by the fact that the White Star Line insured it to the full extent of its enormous value at the lowest rate ever given a transatlantic steamer.

Manned as she was by officers and seamen picked for their ability and experience, had anyone suggested the possibility of her going to the bottom of the sea in less than three hours, he would have been laughed to scorn. And this by those considered the most critical, most discriminating experts on insurance in the world! Proudly we put out this superb floating hotel to sea.

Does the Titanic sink? The largest, most durable, staunchest, most elegant ship in the world? Worth over 7,000,000 dollars, with a cargo reaching well over 3,000,000 dollars, a crew of over 900 trained followers of the sea, and a passenger list of nearly 1,500, including many of the leading men and women of two continents, such a boat sink? Impossible.

Even the idea was ridiculous. And so the ship sped along. Making splendid time and with every promise of a quick, delightful trip, one can easily imagine the general admiration felt for the beauties and comforts of this tremendous ship and the satisfaction that arose from having had the good luck of being with the Titanic on her maiden voyage.

Good luck! What a mocker Fate truly is! With her thousands of twinkling lights, a happy crowd on the deck or in the cabins, and hundreds sleeping with all the confidence that they would have had in their own homes, the hand of destiny suddenly struck without an instant's warning.

With hardly a perceptible shock owing to her enormous size and weight, she received her death blow, and probably a large part of her supposedly impregnable double bottom of steel was cut away as with a knife, opening bulkheads and in an instant rendering useless all her elaborate defense against the sea.

For nearly an hour, hardly anyone except possibly the ship's officers suspected danger. Even when the orders to put on life preservers and embark on women and children went forth, one considered the whole thing somewhat of a lark.

Few were delighted at the break in the monotony and eagerly welcomed the situation as an experience to remember. Without a single doubt, hundreds of people went down sleeping peacefully in their cabins with never a warning of their fate.

But soon, unmistakable evidence of the seriousness of affairs became apparent to those on deck, and they knew a terrible truth. The Titanic, the unsinkable boat—the ten-million-dollar floating palace—with her population larger by far than most of the towns and villages of Great Britain or America—was doomed—she was going down!

Confusion Must-Have Reigned

Confusion must have reigned for a few moments. Here were men and women, wealthy and famous, with everything to make life sweet. Husbands were speeding home to expectant families, wives looking forward to a return to their husbands and homes.

Here were men of great affairs, captains of enterprise with thousands in their service. But instantly, one lost all proportions. In that last short period, men and women were divested of every material value, and rich, powerful, and famous were thrown back to just human beings.

Some unquestionably believed it impossible for the Titanic to sink and, secure in their confidence, preferred to remain on board rather than risk their lives in the lifeboats.

But many knew the truth and left a picture of heroism to the world that time can never destroy. Men whose lives and manner of living had been far removed from hardship or conditions ordinarily looked upon as developing fortitude and courage took their stand side by side with soldiers and sailors trained to meet death bravely.

With sublime heroism in its renunciation of self, husbands and fathers kissed their loved ones goodbye and, with brave smiles on their faces, watched them row away.

No one can read the accounts of the survivors without swelling with pride that manhood and womanhood can ring so true at the supreme moment.

Tears of sadness will fill our eyes, voices will break, and anguish almost overpowers us. However, still, there is an exaltation, a sense of inspiration, that comes from thinking of the nobility of the Titanic's heroes that cannot help but lift and buoy us up in the face of this greatest calamity of modern times.

Let no carping critic of humanity croak again that the flower of chivalry is dead, that men have grown weak, or our civilization has destroyed that courage and bravery.

Let no pessimist tell us the world is going to the bad, that men and women have lost their instincts of honor and self-denial through the struggle for wealth and position.

Let no one say that humanity has lost any part of its nobility or strength as the years have passed.

No, when the traducer of humanity tells us that the days of heroism, devotion, and unselfish love are no more, we have only to point to the Titanic and that last scene that will never be blotted from the memory of man—a great ship—the largest in the world—going down, hundreds waving goodbye and throwing kisses to their loved ones, while the band with unbelievable fortitude was playing that grandest of hymns, Nearer, My God to Thee!

In the dark of night, with all the depressing effects of severe cold, over 1,500 souls met their end and went forth to meet their God. The picture of that tragic moment is the beggar's description. No words can do it justice, and every one of us must shape it for ourselves in our consciousness.

But terrible indeed as the disaster indeed was and empty as it leaves the world and countless families, humanity cannot fail to gain from the chastening effect it must have on every sentient being and the aspiration that every true man must feel that his end shall be as near as possible to that of those who died like men.

As we bring this to a close, we cannot refrain from quoting a verse from Abraham Lincoln's favorite poem, which has always been in the writer's mind since we received the fatal news.

"O, why should the spirit of mortal be proud

Like a swift, fleeting meteor—a fast-flying cloud,

A flash of the lightning—a dash of the wave,

Man passes from life to his end in the grave."

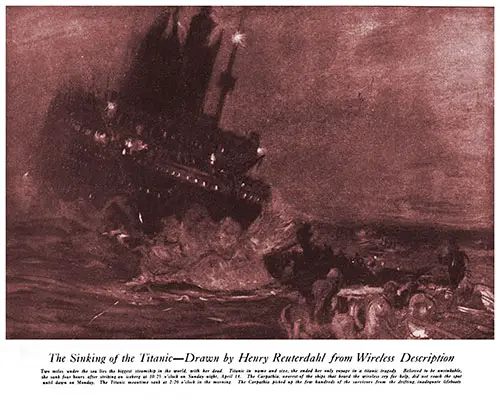

The Sinking of the Titanic, Drawn by Henry Reuterdahl From Wireless Description. Two Miles Under the Sea Lies the Biggest Steamship in the World, With Her Dead. Titanic in Name and Size, She Ended Her Only Voyage in a Titanic Tragedy. Believed to Be Unsinkable, She Sank Four Hours After Striking an Iceberg at 10:25 P.m. on Sunday, April 14, 1912. the Carpathia, the Nearest of the Ships That Heard the Wireless Cry for Help, Reached the Spot at Dawn on Monday. the Titanic Meantime Sank at 2:20 A.m. the Carpathia Picked Up the Few Hundreds of the Survivors From the Drifting, Inadequate Lifeboats. Collier's Weekly Magazine, 27 April 1912. GGA Image ID # 21a2abb7c3

What is the lesson?

What is the lesson? This is, after all, a significant problem. Without a doubt, we have grown arrogant from our progress. We have felt ourselves conquerors of the sea and the elements with our monster ships.

We have magnified our pigmy strength and minimized the enormous powers of nature. In our rush and hustle, we have sacrificed safety for speed.

Restlessness and impatience have controlled us. We have subordinated care and precaution for haste and hurry. Without sense or judgment, we have made foolish drafts on luxury, excitement, and sensational.

And now, when we have to pay, and the collector appears—we find that it is Death! Is it not time to call a halt, to alter our ideas and readjust our values? Is not safety preferable to size and speed? Is it not infinitely preferable to reach our destination a few hours later—but with life and limb intact?

Are four-day boats, eighteen-hour trains, and countless things of the same character worth the price we are paying?

As Charles M. Hays, a great railroad man and one of the Titanic's heroes, said only a few hours before his death. Some great disaster will surely come if the fearful attempts at haste and speed are not curbed.

Little did he know the prophetic character of his remark. The Titanic was sacrificed to false values, the exaltation of size, speed, luxury, and everything appealing to humanity's love for beauty and greatness at the expense of safety and sensible precaution.

Dashing onward at 21 knots (about 26 miles), the danger of icebergs though fully recognized, was never heeded, and we never slackened her pace.

She was to get in on time. Secure in her great size and with blind confidence in her power to triumph over every accident, lifeboat equipment for less than one in three of her passengers and crew was provided.

To reduce the distance and reach her destination quicker, she followed a course known to have its constant dangers of icebergs and floes. Admitting that she was in the usual lane of steamship travel, the fact remains that it was not the safest.

And so we are brought face to face with the grim truth that not the shipbuilders, not the White Star management, not the Captain or his assistants are to blame except incidentally for this awful catastrophe.

The culprits are the people who have encouraged these things and forced their adoption by turning their backs on the cautious and conservative and patronizing only the swiftest, most daring, and most spectacular. Big business is bound to give the people what they want.

If a premium in the form of patronage is given to safety, conservative methods, and common sense, the public will get just these things. But we have given our support and encouragement to the risky, the daring, and the sensational.

Consequently, we the masses are culpable and common decency should make us realize it. We have ignored the substance for the shadow, and it is cruelly wrong to curse and condemn those who have given us what we wanted.

It is only human nature to make someone the goat, but is this fair? Is it right to make those who do our bidding —the officials and subordinates—bear the burden of our indifference or neglect?

Indeed not, and that spirit we proudly call the American spirit of fair play should enable us to be just and generous in this hour of anguish and remorse.

Let us investigate and study the situation in all its aspects and seek as honest, thoughtful men to reach conclusions and decisions that shall correct conditions and prevent a repetition.

But let us take a lesson from our dead heroes and, with respect for their nobility and unselfishness, refrain from making the small, petty mistake of condemning anyone—or any group of men—without the fullest hearing and consideration for their actual responsibility.

In other words, here is the moment for humanity to rise to new heights of fairness, justice, and generosity. We owe it to our dead—but above all to our manhood and womanhood.

The psychology of courage is interesting, but the manifestation of this mental attribute is so interwoven with other spiritual or psychic forces that it is tough to place it and give it its actual value.

Plenty of facts show that courage or bravery in the face of sudden or violent death is most uncertain. Many men who have lived lives and given sufficient reason to lead us to anticipate their highest courage have proven to be the veriest cowards in the end.

On the other hand, plenty of those whose character, temperament, and environment have led them to appear weak, vacillating, and shameful met their fate with the most sublime and splendid courage in the crisis.

Bravery is a most uncertain quantity and can never be predicated on an individual's usual mental qualities or customs. Love, pride, trust in God, the psychology of the moment, the surroundings, the physical condition, and many other factors are all woven into the fabric of courage and heroism, just like fear, despair, lack of control, and some of the same factors that under certain conditions give rise to courage, will cause the most arrant cowardice. No man knows just how he will act at such times until they come.

We all certainly hope we can have the curtain run down at the close and leave behind as clean, noble, and uplifting a scene as that enacted by so many men as the Titanic made her last plunge.

Medical men, with few exceptions, have always died well. The doctors on the Titanic seem to have been faithful to the best traditions of our profession. And after all that is said or done, can one have a better or more beautiful epitaph than Death found him unafraid?

But we who live have our work before us, and this calamity emphasizes certain vital features. The medical profession strives with all its strength and knowledge to save and prolong life.

Does it not behoove us while we drive back the hordes of disease to devote more thought and time to pointing out and urging greater efficiency in preventing needless accidents?

In other words, what is the good of saving countless lives from disease if they are only going to be sacrificed to the Moloch of carelessness and industrial negligence? In all sincerity, we believe medical men should give this matter more thought and devote more attention to arousing humanity from its indifference or ignorance of the physical danger.

"The Titanic Horror," in American Medicine, New York: American-Medical Publishing Company, Complete Series, Vol. XVIII, No. 4, New Series, Vol. VII, No. 4, April 1912, p. 179-182.

Key Points

-

The Unprecedented Tragedy: The article underscores the shock and disbelief that surrounded the Titanic's sinking, a vessel celebrated as the pinnacle of maritime engineering and safety. The belief in its unsinkability was so strong that even the most experienced experts found it inconceivable that it could sink on its maiden voyage.

-

Moments of Heroism Amidst Chaos: The narrative vividly describes the courage and self-sacrifice shown by the Titanic's passengers and crew, highlighting the stoicism of the men who stayed behind to allow women and children to evacuate first. This bravery, especially under such dire circumstances, serves as a reminder of human nobility and courage.

-

Critique of Human Hubris and Materialism: The author offers a critical examination of modern society's obsession with speed, luxury, and technological achievement, suggesting that these priorities contributed to the disaster. The article calls for a reassessment of these values, emphasizing the need to prioritize safety and caution over prestige and convenience.

-

The Role of Society in Shaping Maritime Practices: The piece argues that the public's demand for faster and more luxurious travel led to risky maritime practices. It points out that the shipping companies merely responded to these societal desires, suggesting a shared culpability between the public and the maritime industry.

-

Lessons for the Future: Beyond assigning blame, the article calls for meaningful action to prevent such a catastrophe from happening again. It advocates for a focus on better safety regulations, improved lifeboat provisions, and a cultural shift toward valuing human life and safety over technological feats and speed records.

-

Psychology of Courage in Crisis: The article reflects on the unpredictable nature of courage, noting that bravery in the face of death is not always consistent or predictable. It emphasizes the importance of preparing individuals and societies to meet such crises with dignity and composure.

Summary

In "The Titanic Horror," American Medicine provides a profound reflection on the sinking of the RMS Titanic, emphasizing the emotional and moral lessons stemming from this historic disaster. The article illustrates the world's shock at the loss of what was believed to be an invincible ship, the Titanic. It pays tribute to the heroism of those who faced their doom with courage and critiques the societal obsession with speed and luxury that contributed to the disaster. The piece underscores a collective responsibility, not just for the shipping industry but for society at large, to demand safer practices and to prioritize human life over material achievements. By learning from this tragedy, humanity can hope to foster a more cautious, responsible approach to future endeavors.

Conclusion

"The Titanic Horror" serves as both a lament for the lives lost in one of the greatest maritime disasters of the early 20th century and a call to action for a more conscientious approach to progress and safety. The article does not merely dwell on the tragedy but uses it as a stark reminder of humanity's vulnerability and the need for humility in the face of natural forces. By urging society to reevaluate its priorities—placing safety and precaution above speed and luxury—the piece offers a roadmap for ensuring that such a catastrophe does not happen again. In honoring the heroism of those who perished and critiquing the arrogance that led to the disaster, the article becomes both a tribute and a powerful lesson in the value of human life.