The Titanic Tragedy - 1912

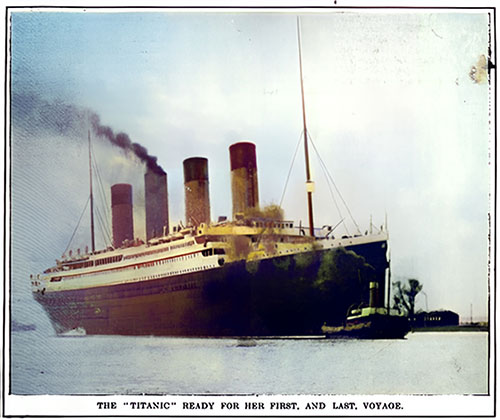

The RMS Titanic Ready for Her First and Last Voyage. The Literary Digest (27 April 1912) p. 867. GGA Image ID # 1084c9f3c4

Introduction

"The Titanic Tragedy," published in The Literary Digest on April 27, 1912, is a comprehensive and emotional analysis of the catastrophic sinking of the RMS Titanic. The article goes beyond recounting the event, delving into the public outrage and critical commentary that emerged in the wake of the disaster. It discusses the avoidable nature of the tragedy, the lack of adequate safety measures on the ship, and the dangerous prioritization of speed and luxury over safety by the White Star Line and its competitors. This article captures a moment in history when technological pride clashed with human vulnerability, highlighting the need for accountability and reform in maritime safety.

There are tears for the dead, pity for the bereaved, and pride in the heroic victims of the Titanic disaster. Still, there is some pretty stern comment, too, on the fact that in this year 1912, the greatest of all ships, the unsinkable Titanic, should, upon her maiden voyage, carry down to Death 1,635 men and women while but 705 were rescued from a calm sea on a starlit night.

The dramatic circumstances and the long death roll, including many of the world's most honored names, make this the greatest ocean tragedy of modern times.

But what remains etched in the minds of those who have been grappling with this tragedy is the stark fact that the loss of life was not just a tragedy, but a needless, wanton, and wholly avoidable sacrifice. Many an editorial on the Titanic's demise bears the brief but damning caption: MURDER.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, there was a significant public outcry, with many expressing their shock and anger. In this turmoil of protest and denunciation, two questions press relentlessly for an answer.

First: Why was the Titanic driving ahead practically full speed along a dangerous course through icefields after receiving repeated warnings from nearby bergs?

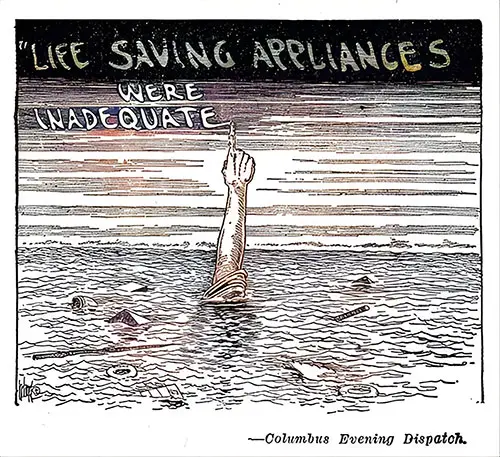

Then, why was this mighty vessel allowed to start across the Atlantic with so few lifeboats that less than half of those on board could have been saved even if proper arrangements had been made for launching and operating the boats?

The answer, as found by the daily press, to the first question is that this steamship company, like its competitors, and with the tacit approval of the traveling public, prioritized speed over safety.

And they point to this statement of the Titanic's quartermaster, who was at the helm at the time of the wreck, responsible for steering the ship: We were crowding her to the limit. We sealed on every ounce of steam, and she was under orders from the general officers of the line to make all the speed of which she was capable.

We had covered an astonishing 565 miles that day and were hurtling at a breakneck speed of twenty-one knots when we collided with the iceberg. The officers were under pressure to break a record, and they were pushing the ship to its limits.

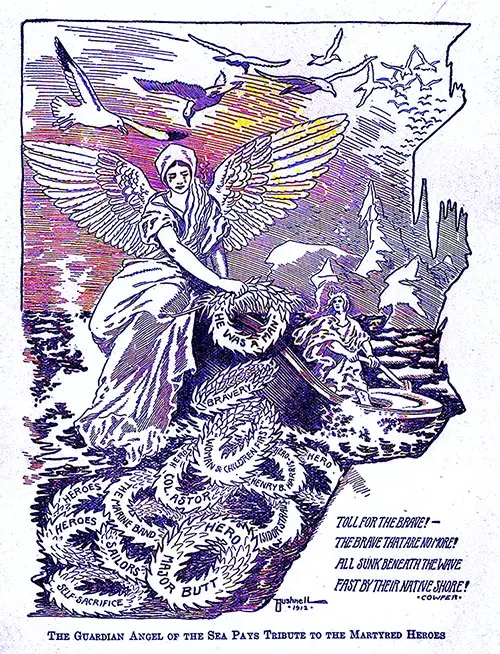

Guardian Angel of the Sea Pays Tribute to Martyred Heroes. The toll for the Brave! The Brave That Are No More! All Sunk Beneath the Wave, Fast by Their Native Shore! - Cowper. © Bushnell 1912. Wreck and Sinking of the Titanic (1912) p. 10. GGA Image ID # 108998cc7f

Captain Smith of the Titanic, who went down with his ship, admitted her inadequate life-saving equipment while still under construction. He attributed this to the belief of the owners and designers that the boat, because of her size, strength, and watertight compartments, was practically unsinkable and that, in any case, she could keep afloat until her wireless outfit would bring help.

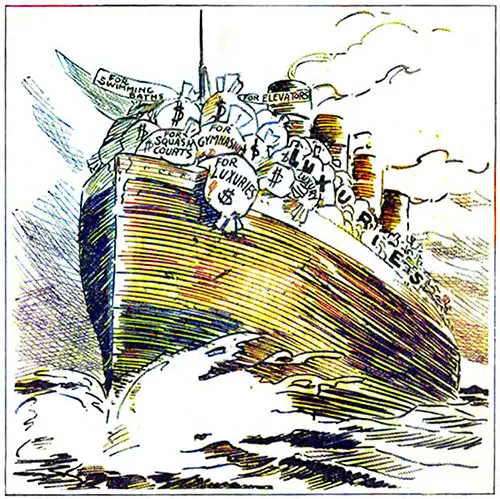

But an observant editor who picked up a White Star Line folder in a streetcar found this list of luxuries provided on the Titanic a scathing piece of reading:

- Sports decks and spacious promenades

- Commodious staterooms and apartments en suite

- Cabins deluxe with bath

- Squash-racquet courts

- Turkish and electric bath establishments

- Salt-water swimming-pools

- Glass-enclosed sun parlors

- Veranda and Palm Courts

- Louis XVI restaurants

- Grand dining-saloons

- Electric elevators

That is, in providing excessive luxury, we sacrificed necessary safety. This is asserted on every hand, and this statement from an explanation made by a White Star Line official after the loss of the Republic three years ago is now considered very significant.

Luxuries of Modern Travel -- But Not Enough Lifeboats. © Montreal Herald. The Literary Digest (4 May 1912) p. 925. GGA Image ID # 10868883f9

It is well-known that a steamship in passenger service can't carry enough lifeboats to accommodate all hands at once. If we did this, so much room would be utilized for lifeboats that passengers would have no space left on deck. The ships would carry the necessary number of lifeboats at the cost of many present comforts of our patrons.

The Titanic, a symbol of opulence and grandeur, reigned as the queen of the seas, the largest and most luxurious ship afloat, for a mere five days. Embarking on her maiden voyage from Liverpool on Wednesday, 14 April, she carried an impressive list of passengers who anticipated a week of unparalleled pleasure, surrounded by every conceivable comfort and luxury.

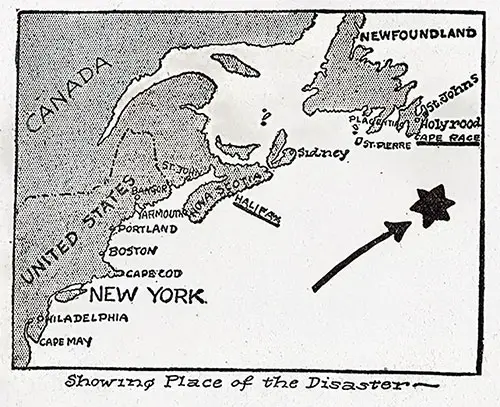

On the following Sunday evening, she was 400 miles off Cape Race. The sea was smooth, the sky clear. Despite repeated warnings of icebergs from other vessels and the presence of much-floating ice, she was steaming ahead at a speed of probably 21 knots.

Toward midnight, an iceberg was seen ahead. It was too late to slow down or turn aside, but the ship swerved slightly from its course and struck the berg with a glancing blow, possibly sliding up on a submerged portion of it. The shock was not violent, but the Titanic sent wireless calls for help, and the passengers were called on deck.

The officers soon found that an iceberg had ripped out the side and bottom of the ship and that it was simply a question of how long her pierced air compartments and leaking bulkheads would keep the Titanic afloat.

Despite the varying details, the stories all agree on one point-the remarkable heroism displayed by the officers and male passengers aboard the Titanic. The New York papers, in particular, highlighted the detailed, coherent, and consistent account of Mr. R. W. Daniel, one of the survivors who arrived in the harbor the day after the Carpathia with its pitiful load.

After the Titanic struck the iceberg, it continued for about a mile before coming to a halt, as Mr. Daniel recounts. The passengers, gathered on the deck, initially remained calm, reassured by the belief that the Titanic was unsinkable. However, as the order to board the lifeboats was given, many hesitated, feeling safer on the seemingly invincible ship.

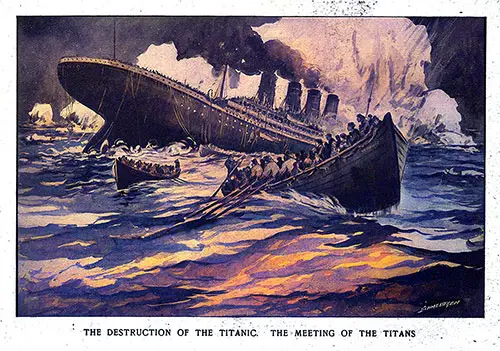

Destruction of the Titanic. Wreck and Sinking of the Titanic (1912) p. 34. GGA Image ID # 108a4f13cf

To quote at some length from Mr. Daniel's statement, as it appears in the columns of the New York Evening Post:

- I learned later that there was a conflict in orders when the lifeboats were filled. On the starboard side, husbands were ordered to enter the smaller craft with their wives. On the port side, husbands were driven back, the order being women and children first. That explains why so many men survived.

- In many instances, within the range of my vision, wives refused point-blank to leave their husbands. I saw crew members tear women from men's arms and throw them over the side of lifeboats. Mrs. Isidor Straus clung to her husband, and no one could force her from his side.

- They have lasted two hours between the Titanic striking the berg and her foundering. Not until the last five minutes did the awful realization come that the end was at hand.

- Deck after deck was submerged. There was no lurching, no grinding or crunching. The Titanic settled. I was far up on one of the top decks. Two minutes before the final disappearance of the ship, I jumped.

- About me were many others in the water. My bathrobe floated away. It was icily cold. I struck out at once. Before the last, I turned. My first glance took in the people swarming the Titanic's decks.

- Hundreds were standing there, helpless to ward off the approaching Death. I saw Captain Smith on his bridge. My eyes seemingly clung to him. The deck from which I had leaped was immersed; the water had risen slowly and was now to bridge. Then, it was at Captain Smith's waist. I saw him no more. He died a hero.

- The bow of the Titanic was far beneath the surface. Only her four monster funnels and the two masts were visible to me. It was all over in an instant. The Titanic's stern rose entirely out of the water. Up it went, thirty, forty, sixty feet into the air, then, with her body slanting at an angle of 45 degrees, slowly, the Titanic slipped out of sight. There was very little suction.

- Until I die, the cries of those wretched men and women who went down clinging helplessly to the Titanic's rail will ring in my ears. Groans, shrieks, and almost inhuman sounds came across the water.

- I turned and swam. When I pulled into the lifeboat, it was an hour later, but I knew nothing. The water was numbing me. Only the preserver about my body saved my life.

- This sturdy swimmer is one of many who declare that if the steamship company had provided proper life-saving devices, not a soul on board would have been lost.

- The Titanic lay on the water, settling slowly. The sea was calm. Boats and rafts were put overboard without difficulty until there were no more.

The Carpathia, summoned by wireless, as were other ships too far away to be of service, reached the spot about daylight and rescued those aboard the 16 boats still afloat and a few from rafts.

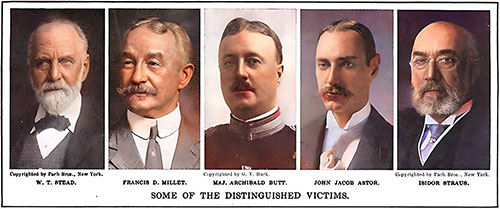

Some Distinguished Victims include W. T. Stead, Francis D. Millet, Major Archibald Butt, John Jacob Astor, and Isidor Straus. The Literary Digest (27 April 1912) p. 866. GGA Image ID # 1084a54b26

Among the dead are such well-known men as John Jacob Astor, Isidor Straus, William T. Stead of the English Review of Reviews, President C. M. Hays of the Grand Trunk Railroad; F. D. Millet, the artist; Jacques Futrelle, novelist; Henry B. Harris, theatrical manager; Major Butt, President Taft's military aid; J. B. Thayer, vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad; Benjamin Guggenheim, George D. Widener, and W. A. Roebling, 2d.

Many of the rescued women are widows; several, like Mrs. Astor, are brides of a few months. The presence of a few men among the survivors is readily accounted for by the need for strong arms to row the boats and circumstances like those noted by Mr. Daniel.

But the fact that Mr. J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, was saved in a lifeboat leads even a careful paper like The Wall Street Journal to inquire: Is there any passenger who should not have found a place in the lifeboat before the greatest or least official of the line?

The further inference by many that Mr. Ismay was responsible for urging the Titanic to such excessive speed does not increase their very slight feeling of charity toward him. Though he was initially denounced as a coward by the more radical press, we later gave space to his concise account of the circumstances of his departure.

Excerpts from Mr. Ismay's statement before the United States Senate Investigating Committee in New York:

The lifeboat was there, and the crew had loaded a certain number of the women. The officer called out to any other women on the deck to come. There were no other passengers, men or women, on the deck, so I got in. That is all there is to it.

Perhaps some of us have smiled inwardly at the church prayer for someone's preservation from the dangers of the sea and safe conduct to the haven where he would be, like an old-fashioned petition in these days of rapid ocean transit.

But we now know, as the Chicago Tribune remarks, that perfect safety in ocean travel is fiction at a high cost. The Titanic disaster reminds the Baltimore Sun that despite all our progress, perils still exist. Before the forces of untamed nature, man is often as helpless as an infant.

The iceberg, others tell us, is still the tremendous unconquered peril of the North Atlantic. When the unsinkable ship meets the irresistible iceberg, she meets the same fate as the fisherman's dory.

However, the generality of editors, though they admit the dangers of a season when the ice has come south farther and sooner than usual, can see little excuse for the loss of the Titanic.

Map Showing Place of Disaster. Wreck and Sinking of the Titanic (1912) p. 106. GGA Image ID # 108c85c368

True, icebergs are dangerous, but peril should not be invited by rushing ahead at night through such perilous sea lanes at high speed after repeated warnings. Nothing but speed madness, they say, can account for it, nothing but the insistence of the company's officials that they should break a record on her maiden voyage.

We are told this made the experienced navigator in command take chances and end an honorable and efficient career by going down with his ship and two-thirds of the passengers entrusted to his care.

Heedless of warnings and indifferent to disaster, the White Star officials raced with Death, and Death won, as the New York American puts it.

Other papers in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Washington assign the company the responsibility, as does the New York World, which adds that "the public that has encouraged and inflamed this speed madness must share the blame.

The New York Commercial asks its readers not to blame steamship owners too severely without considering what is permitted on shore every day.

Furthermore, according to all the wreck accounts, a sufficient number of lifeboats, adequately equipped and with a ship's crew drilled in their use, could have saved practically every person on the Titanic.

And there is a brief editorial paragraph in the New York Herald which sums up an opinion held in nearly every newspaper office where the press wires have carried the news of the Titanic's loss. Says the Herald: Had this latest expression of mercantile naval construction been supplied with fewer fol-de-rols, such as gymnasiums, swimming tanks, and other non-essentials to safety at sea, more boats and liferafts could have been carried—and every life has been saved under the conditions that prevailed when the Titanic received her death blow.

It is abundantly evident to the New York Evening Post that on both sides of the ocean, public opinion is fastening upon the deficiency of lifeboats as the one great lesson of neglect bitten in by the awful loss of life on the Titanic.

Or, as the Newark News and New York Sun regard the lesson thus taught the world, it is, to quote the New York paper, the need for an international system of inspection and equipment and uniform requirements as to sufficient lifeboats and liferafts for all on board—every passenger, every officer, every member of the ship's force.

In this connection, it is to be noted that Congress is now investigating the loss of the Titanic, that the British Parliament will do likewise, and that several measures have been proposed in each body to ensure stricter requirements and more careful inspection.

As for suggestions to prevent the repetition of such sea tragedies as the sinking of the Titanic, their name is legion. Powerful searchlights, geophones, micro thermometers, and other devices to detect the presence of icebergs are endorsed by their inventors and others.

There is the idea of a scout boat to go ahead of the great steamship, as a pilot locomotive is sometimes sent ahead of its special train. One newspaper strongly urges the Government or International Patrol of the North Atlantic during the dangerous season. Another would have all liners cross in pairs, near enough so that one could render assistance if the other met with a mishap.

Life-Saving Appliances Were Inadequate. © Columbus Evening Dispatch. Wreck and Sinking of the Titanic (1912) p. 310. GGA Image ID # 109540d739

A striking article, written some time ago for The Navy (Wash) by Captain E. K. Roden, has been widely quoted by the press since the loss of the Titanic. The writer asserts that safety appliance improvements on passenger ships must catch up with the growing demand for luxury and comfort in ocean travel. Shipping men have been quoted saying that these luxuries are offered because the public demands them. No, replies the New York Evening Post.

Each line seeks to outdo the other in new and original features so that their press agents may have more to talk about and that the newspapers will give more space to descriptions of the extraordinary success they have attained in duplicating on the ocean all the features of the most luxurious modern hotels. Then they forget to make a few thousand dollars of expenditure necessary to buy sufficient lifeboats and rafts but tell us that it is all the public's fault!

In the same editorial, The Evening Post points out some good results likely to come from this horror. Every humanitarian advance in the world's history of shipping has been purchased by suffering or loss of life. It is not only in the history of shipping, says the Philadelphia North Americans.

It took horror heaped upon horror to establish the aggression against existing property rights that lay in denying capital the freedom of investment in hotels and tenements without fire escapes. The Titanic disaster meant the end of allowing unsinkable ships to sail with one-third of the proper number of lifeboats.

On the Titanic, on General Slocum, as in the Triangle Shirtwaist factory, on railroads that fail to provide safety appliances, and in factories where the workers are regarded as the cheapest raw material, the system is the same—gambling with human life for dollar profit.

"Topics of the Day: The Titanic Tragedy," in The Literary Digest, New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, Vol. XLIV, No. 17, Whole No. 1149, 27 April 1912, p. 865-869.

Key Points

-

Public Outcry and Blame: The tragedy sparked widespread outrage and grief, as many saw the disaster not just as an unfortunate accident but as a "needless, wanton, and wholly avoidable sacrifice." Many editorials labeled it as "murder," pointing to the deliberate negligence of safety measures.

-

Prioritization of Speed Over Safety: One of the critical criticisms was the decision to push the Titanic at full speed through a known icefield despite multiple warnings. The crew's pressure to break speed records reflects the competitive atmosphere among shipping lines at the time, prioritizing prestige over passenger safety.

-

Inadequate Lifeboat Provision: The article highlights a significant failure in safety protocols: the Titanic did not have enough lifeboats for all passengers and crew. Despite the ship's massive size and luxurious amenities, it lacked sufficient life-saving equipment, a decision influenced by the desire to maximize comfort and luxury on deck rather than prioritize safety.

-

Heroism and Human Spirit: Amid the disaster, the narrative focuses on the courage and self-sacrifice of many passengers and crew, particularly the men who stayed behind to allow women and children to board the lifeboats first. The behavior of Captain Smith, who went down with his ship, is also noted as exemplary of leadership in a crisis.

-

Criticism of White Star Line and Ismay: The White Star Line, and particularly J. Bruce Ismay, its managing director, faced severe backlash. Ismay's survival while many others perished led to widespread condemnation and calls for accountability. The article examines his controversial actions and the public's perception of them.

-

Call for Reforms and Safety Measures: The tragedy led to a push for improved safety standards, including more lifeboats, better equipment, and stricter regulations. Proposals for various technological improvements and international cooperation to ensure safer maritime travel were also discussed.

-

Reflections on Modern Civilization: The article concludes with a broader reflection on the hubris of modern civilization. It criticizes the era's obsession with luxury, speed, and technological achievement at the expense of human life, suggesting that society needs to reassess its values.

Summary

"The Titanic Tragedy" provides an in-depth examination of the catastrophic sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912, emphasizing the avoidable nature of the disaster and the broader societal issues it reflects. The article captures the public outrage and grief that followed the tragedy, highlighting the glaring negligence of safety in favor of speed and luxury by the White Star Line and its competitors. It critiques the inadequate lifeboat provisions, the pressure to break speed records, and the perceived complacency of those in charge. While it acknowledges the heroism displayed during the disaster, it also underscores the need for systemic reforms in maritime safety, urging a reevaluation of priorities to prevent future tragedies. The article ultimately serves as both a lament for those lost and a call to action for a safer and more responsible approach to progress.

Conclusion

"The Titanic Tragedy" stands as a poignant reminder of the perils of hubris and the devastating consequences of placing prestige and luxury above human safety. The article calls for accountability from those in positions of power and urges society to learn from the lessons of the disaster. By highlighting the shortcomings in safety measures and the need for reform, it reflects a critical moment in history when the limits of human achievement were starkly laid bare. The tragedy of the Titanic continues to serve as a cautionary tale, emphasizing that no matter how advanced civilization becomes, humility and respect for the forces of nature must always guide our endeavors.